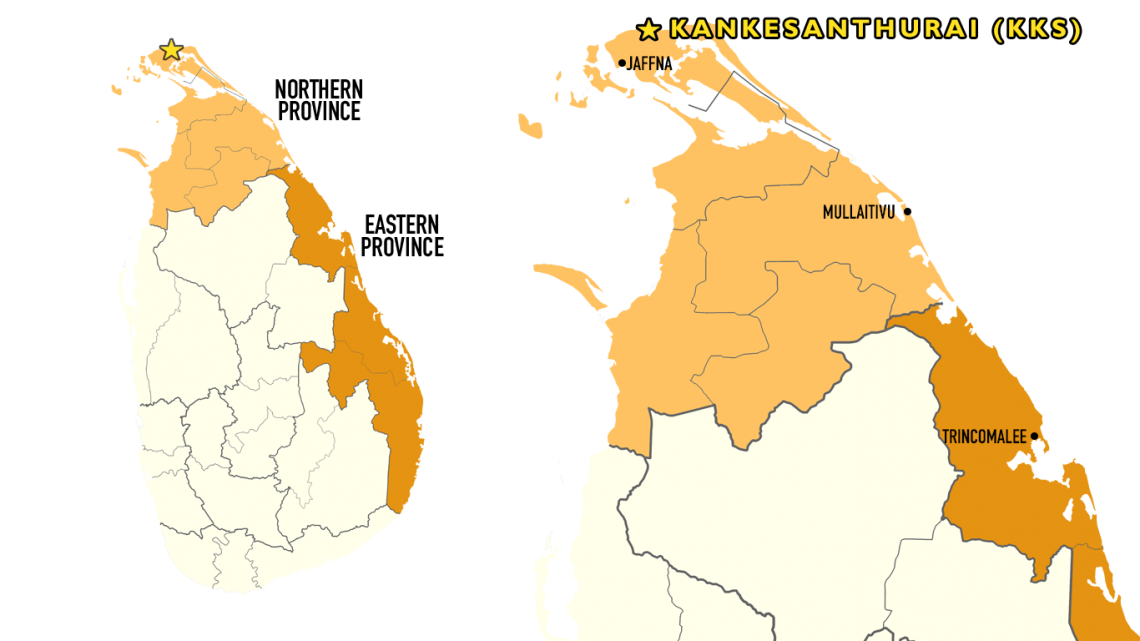

Reporting on the continued militarization of the North-East, PEARL (People for Equality and Relief in Lanka) highlights that in Kankesanthurai (KKS) region there is “least 40 military bases, 4 police institutions, 4 army canteens and resorts, and 3 Buddhist temples” within just 90 square kilometres of land.

The Sri Lankan military’s declaration of KKS as a “High-Security Zone”, has rendered the former thriving fishing and manufacturing site, inaccessible to former Tamil-speaking residents. The area, which was once considered the “lifeline of the Jaffna peninsula”, has seen Tamils lose their “homes, lands, and livelihoods”.

KKS fell under Sri Lanka’s Naval control between 1983 and 1993 and was consequently closed off to the Tamil public. However, as PEARL notes, it follows a longer history of economic discrimination. In the early 70s, KKS harbour was rejected as a suitable port following pressure from Buddhist monks and Sinhala extremists. This was detrimental for the Tamil economy as the harbour would have been crucial in “promoting free trade globally to and from the Tamil homeland but was left undeveloped by the state” and went against World Bank recommendations. Sri Lanka’s regulations prevented the establishment of Free Trade Zones outside of Colombo, ensuring that the economic benefits accrued to Sinhala-dominate regions.

PEARL further notes that during its period as an electoral district there were further issues resolving problems “relating to colonization of Tamil districts, educational and employment opportunities, funds for the development of irrigation, agriculture, and industries”.

Since the end of the armed conflict, PEARL notes that the region has “evolved towards maintaining the normalization of surveillance and intrusion into Tamil civilians’ lives, while serving as a gateway to engage in Sinhalization of the region”.

Since 2011, the Sri Lankan government has rolled back regulations governing High-Security Zones, but many regions including KKS remain inaccessible to former residents. Some reported barriers including: “army camps remained and were even reinforced with barbed wire fencing”; “village roads remained unreleased”; “old homes and infrastructure were completely destroyed”.

PEARL further reports that Sri Lanka’s former army commander and colonel of Sri Lanka’s Special Forces Regiment, Mahesh Senanayake threatened residents during a land release event, saying “Tamils’ lands could be just as easily taken back by the armed forces that returned them”.

The militarisation of KKS and its surrounding areas has rendered fishing ports inaccessible to Tamil residents and increased surveillance on the Tamil public. This has led to increases in harassment of Tamil residents as well as increased attempts at suppressing memorials, such as the annual Thileepan Remembrance.

PEARL further notes, that recently a Sri Lankan navy sailor from the KKS base was arrested by the Criminal Investigation Department for his involvement in the abduction and disappearance of 11 Tamil youths between 2008 and 2009.

Read the full report by PEARL here.