He was my favourite uncle, the youngest in my mother’s family, who was named after the Tamil deity, Lord Murugan - the true protector of language heritage and the Tamil culture, as my grandmother (Ammamma) would always say. He was her last son, her favourite. A most mischievous being that she loved and spent the majority of her final years protecting. He survived abuse during the time the Indian army came onto the island and lived through war and witnessed the genocide of his people, before he was forced to let go of the one person he dreamed of sharing his life with.

Fluent in five languages, my uncle was a man of great knowledge, who enjoyed reading and learning about other language as much as he loved his mother tongue. Aside from his love towards his work, family and literature, he had a soft spot for the love of his life, his wife.

Mala was just an ordinary village girl, who dressed simply, hadn’t studied much and didn't have much wealth. Some would even have questioned what was so special about her. However, what we saw on the outside was just portion of what a true gentle being she was on the inside.

Their love started when he was working as a postmaster in Mankulam, where the two would often pass each other on the streets or in person when my aunt would come to drop off the post. Just as their relationship flourished however, my uncle was arrested by the Indian army.

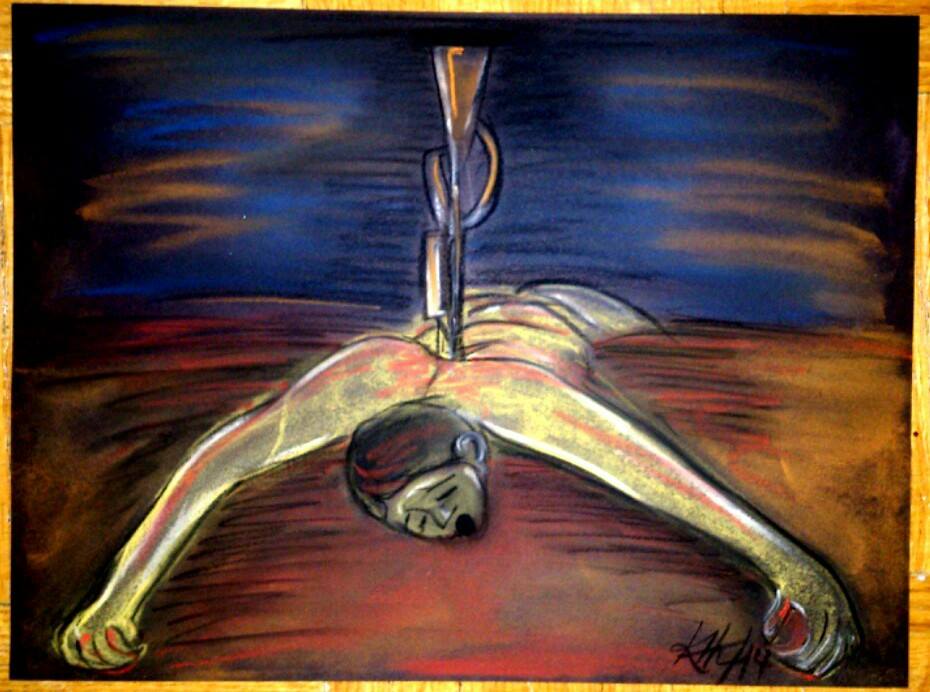

Abused both mentally and physically, the Indian army interrogated him regarding the whereabouts of the LTTE and its leader V Prabhakaran. He told us later that he never thought he would make it out alive. He spent his days thinking of what would happen to his mother, his siblings and the girl he had fallen in love with, hoping that someone would secure his release.

No one came though, not even my grandmother, as his arrest and interrogation was done in silence. My grandmother went to different police stations and army camps day and night, waiting and inquiring about her son. It was many months before she finally found out where he was being detained.

Thirty months after his arrest, my uncle was released. He came out frail with bones protruding from his sunken, bruised skin, which bore the marks of days and nights of beatings. Unable to walk, he limped. His eyes red, lips cracked and his cheeks hallowed out from the loss of teeth.

Overjoyed by his release, Mala came running to see him. He remained silent though and avoided her gaze, as the memories of the abuse and torture he had experienced poured from his eyes. Pushing her away he told her to leave him and live her life with someone who could make her happy and allow her to lead a normal life. He began to avoid her despite her refusal to leave him for any other.

Mala eventually tried to kill herself. “I either live with you or not live at all,” she said.

Forced to accept the sincerity of her love for him, my uncle gave in and they married.

Life went by slowly, years turning into decades. The war was no better however, it darkened like grey clouds before a horrific storm. When that storm eventually came in 2009, its horror was unimaginable

Like all that hoped to survive the Mullivaikkal genocide, my aunt and an uncle walked barefoot for days looking for shelter and refuge. Hungry and thirsty they drank the muddy waters they came across as they stepped over dead bodies. After a few days they finally reached a camp. It was cramped, and the heat made it stickier. There were babies, children, widows, mothers, the young, the old, the sick and the injured. This was considered the safe place to be, although there wasn't enough food or water. My uncle prayed day and night that our family would be safe.

My aunt had always been a petite woman. Walking for days without clean water, food and with open wounds in the heat began to take its toll on her slender frame. She was soon unable to stand as an infection raged through her body. Her fever was uncontrollable.

In desperation my uncle told the army officers at the camp that his wife needed urgent medical attention. Saying the camp did not have the facilities to take care of her, the officers told him they would take her to another camp a few miles away. Agreeing, he helped get her ready. The soldiers lifted her onto a stretcher and put her in the ambulance. My uncle got in and sat by her holding her head.

“You can't come with us,” one of the army officers told him. “You can see her at the camp once we give her treatment.” The ambulance attendees told him the name of the camp and how to get there as he got off the ambulance. He saw his wife one last time before the ambulance doors closed on him and drove off.

He stood speechless for a few hours. He inquired at the camp when he would be able to go see his wife and was told he could go tomorrow.

Tomorrow soon became the next day, then the day after that. Soon days turned into weeks, weeks into months. The war ended. The genocide complete. The mass piles of bodies burned into ash. The lakes of blood dried out.The blood stained ground covered with new construction so traces of the slaughter would be hidden as if hundreds of thousands of people unaccounted for had disappeared into thin air. As if the ones who languish from place to place mourning for their dead and searching for their missing were looking for someone from their imagination.

My uncle chased after every ambulance hoping still to see my aunt was inside it. He searched every hospital and questioned local officials about her whereabouts. Silence was the answer he received. Their silence muted him. It took away his feelings, blinded his mind and crippled him mentally, torturing him as he constantly thinks of how he failed to be there as her husband, partner and lover to protect her.

Almost a decade later, my uncle still hopes to see her one last time, to tell her he loves her, that he will protect and that they can be together for the remainder of their lives. Like him, we hope to find her. Hope to give him the peace he needs, and let their love live, like in his dreams. However, he has changed forever – his body is alive, but his soul and essence was lost in 2009.