The election of Joe Biden as the 46th President of the United States, as well as Kamala Harris as the first Black and Tamil female Vice President, has been touted as a victory for international multilateralism and the “restoration of America’s moral leadership” in the world.

In Biden’s manifesto, he announces that within his first year in office he will host a “Global Summit for Democracy” a key aim of which will be “advancing human rights” and “defending against authoritarianism”.

In an era in which the international community is backsliding on its commitments to Eelam Tamils and to human rights in Sri Lanka more generally, “moral leadership” is in dire need. However, the question remains will a Biden-Harris administration follow through?

Moral leadership

During his tenure as Vice-President, Biden served under the Barack Obama administration. A hallmark of the administration was strong rhetoric on issues of human rights and democracy, but an apparent inability to follow through. Having assumed the presidency at the height of Sri Lanka’s massacres in 2009, the United States had already placed its backing behind Colombo's military strategy. As the atrocities continued, Obama though personally spoke out against Sri Lanka’s excesses and atrocities.

On 13 May 2009, after the indiscriminate shelling of hospitals and civilian populated no-fire zones, the newly inaugurated president addressed Sri Lanka from the White House lawn.

“First, the [Sri Lanka] government should stop the indiscriminate shelling, ... including [of] several hospitals, and ...

“... the government should live up to its commitment to not use heavy weapons in the conflict zone.

“Second, the government should give UN humanitarian teams access to the civilians who are trapped between the warring parties so that they can receive the immediate assistance necessary to save lives.

“Third, the government should also allow the UN and the International Committee of the Red Cross access to nearly 190,000 displaced people ... so that they can receive the support that they need.”

The faith in Colombo to heed his call, however, was misplaced. Obama's call was followed by no immediate tangible consequences for Sri Lanka as the crimes continued, and instead appeared empty.

Sri Lanka refused to comply, and an estimated 70,000 civilians were slaughtered during those final six months. Colombo alleged that it was conducting a “humanitarian mission” and has continued to deny credible allegations of summary executions, torture, sexual violence, and genocide. Those who dared to give evidence of Sri Lankan war crimes would be hung as traitors, threatened then defence secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa.

Empty Rhetoric

After years of committed Tamil lobbying and pressure on the international community, in March 2012 a landmark resolution was passed at the UN Human Rights Council. Despite Sri Lanka’s best efforts, including the intimidation of human rights activists in Geneva, the resolution was passed with firm backing from Washington.

“Our view is that if there isn’t some form of truth and accounting of these kind of mass-scale atrocities and casualties, you can’t have lasting peace,” Eileen Donahoe, the United States ambassador to the Human Rights Council, said after the vote. “You sow the seeds of future conflict.”

US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said in a statement released hours after the vote that the United States and the international community “had sent a strong signal that Sri Lanka will only achieve lasting peace through real reconciliation and accountability.”

Just weeks later, in May 2012, Clinton spoke to GL Peiris on issues accountability, free media, human rights and demilitarising the North-East. When asked if accountability would mean prosecuting Sri Lankan war criminals, US State Department spokesperson, Victoria Nuland stated, “This is precisely what we mean when we talk about accountability in all of it”.

The move was reportedly rejected within hours by then Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa.

Photograph: Power with Tamil journalists in Jaffna

As Sri Lanka continued to reject accountability measures, repeated resolutions continued to be brought at the UN Human Rights Council, with Tamils making clear that more consequential action was required.

In November 2015, US envoy to the United Nations, Samantha Power, visited Jaffna and during her visit praised the resilience of Tamil journalists. She also demanded an ended to militarisation stating, “demilitarisation in Jaffna cannot wait”. A year prior she had stated that “accountability was overdue in Sri Lanka”.

After 5 years in which the #SriLanka gov't has undermined democracy & refused to investigate war crimes allegations, accountability overdue.

— Samantha Power (@AmbPower44) March 28, 2014

There seemed to be a genuine conviction of Power’s dedication to alleviating Tamil suffering. Power, after all, had covered the atrocities in the Bosnian genocide as a reporter. As a Harvard Law alumnus, her passion for human rights would lead her to write the Pulitzer Prize-winning, “A Problem from Hell” in which she documented the US failure to intervene and prevent genocide.

A UN investigation had concluded that mass atrocities had taken place and yet another resolution mandated a court with international judges and lawyers to prosecute perpetrators. Sri Lanka and the Rajapaksas, it seemed at least, were beginning to feel some international pressure.

International backsliding

The Obama administration’s combative rhetoric, however, would slip away and be followed by a failure to commit to tangible actions. As a new regime came to power in Sri Lanka, US pressure faltered. Despite the continued rejection of UN resolutions and failure to account for the crimes of 2009, Power would go on to describe Sri Lanka as a “global champion of human rights” in 2015. This remark prompted fierce criticism from a range of human rights advocates.

Abarna Selvarajah and Brannavy Jeyasundara maintain that the relatively relaxed position of the international community was due to a misplaced faith of the “comparatively more moderate” candidacy of Maithripala Sirisena, under the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) and with the backing of the United National Party (UNP). This, they write, furthered “collective and self-serving amnesia of the Tamil genocide by the international community” following Sirisena’s victory.

Taylor Dibbert said in The Diplomat, at the time, that Washington's rhetoric "continues to be wildly out of step with reality".

"Sri Lanka watchers will notice that instead of the United States clearly calling for accountability for wartime abuses (a hugely controversial issue in post-war Sri Lanka), the language seems to have shifted to 'accountable democracy.' This is something to watch going forward. Is Washington still genuinely pushing for wartime accountability?" he wrote.

"Sri Lanka’s new government has ruled in a less authoritarian fashion than the administration of Mahinda Rajapaksa, though it’s unclear how or when Colombo became a “global champion” of human rights and accountability. The truth is that we’re still waiting for the government to move toward deeper reform. Besides, the recent spate of arrests and abductions across the Tamil-dominated Northern and Eastern Provinces should set alarm bells ringing in Washington. That’s the type of anti-Tamil behaviour that became increasingly common during Rajapaksa’s divisive decade in power,"

The belief of US leadership at the time was that Sirisena administration could be worked with. Yet, as Tamil voices continued to protest louder than before - particularly the Tamil families of the disappeared who continue their protest to this day - remarkably little progress was made. And as international pressure on Sri Lanka eased, the Rajapaksa regime organised a resurgence. Sri Lanka's 2019 Presidential elections saw viole ant backlash towards the previous administration. The UNP lost all but one National List seat. They were tarred by the Rajapaksas as a government who were “treasonous” for their “somewhat feeble attempts to address the Tamil question via constitutional reforms and accountability”, write Mario Arulthas and Madura Rasaratnam.

The US leniency with the Sirisena administration had failed resoundingly.

Present-day

Whilst Sri Lanka has flagrantly disregarded their previous commitment to the UN Human Rights Council; appointed war criminals to cabinet positions; and, radically decreased presidential accountability; the international community continues a policy of inaction, devoid of the principled leadership that is needed for change.

In just the past weeks the UN held a virtual conference featuring Sri Lanka’s prime minister and accused war criminal, Mahinda Rajapaksa, as a “Chief Guest”. The move was criticised by Human Rights Watch as a “slap in the face for victims of human rights abuses and war crimes.”

“Instead of focusing on them, the UN chose to honour one of the people implicated in their suffering, the country’s prime minister, Mahinda Rajapaksa…To add insult to injury, the government has opposed victims’ demands for justice- something the UN strongly supports,” the rights group said.

In response to this condemnation, a local UN official in Sri Lanka responded to the condemnation by laughing at the concern expressed. The news follows a decision by the European Union to continue GSP+ trade benefits for Sri Lanka despite a clear failure by the government to repeal the draconian Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), a key commitment made by Sri Lanka under the scheme and the UN Human Rights Council.

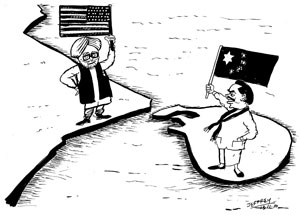

Similarly, during a diplomatic visit by top Chinese officials, there was a pledge that China would defend Sri Lanka at “international fora including United Nations Human Rights Council”.

International pressure slipped and has not returned.

The China factor

![]()

Sri Lanka meanwhile has continued to build its relations with China and in particular relied on Beijing's loans. China’s advances within Sri Lanka have taken the form of large-scale infrastructure projects such as the establishment of Hambantota Port and the Lotus Tower. Sri Lanka’s Treasury has also recently announced yet another US$ 500m concessionary loan from China which is due to be repaid during a 10-year period.

During that final phase of the armed conflict, China boosted its military aid five-fold, becoming Sri Lanka’s largest donor and providing fighter jets, antiaircraft guns, JY-11 3D air surveillance radars. This weaponry played a central role in the Sri Lankan military successes and its genocidal violence. That relationship has continued to grow.

Alyssa Ayres, Senior Fellow for South Asia at Council on Foreign Relations, said that one reason for Sri Lanka’s pivot towards China is its willingness to lend money without any human rights linked conditions.

“I think there was a real sense that the earlier Rajapaksa government had definitively decided to put its eggs in China’s basket, not only because China was a terrific infrastructure investing partner […] But it also was a partner that didn’t ask questions about the very important human rights issues still at play in Sri Lanka and that have been”.

Cartoon published in The Island Dec 1, 2010

The threat of a Chinese debt-trap has animated much discussion, however, as Gajan Raj notes, it ignores “Sri Lanka’s historic tendency to seek out and strengthen links with powers unfriendly, or hostile, to India at any given time”. Sri Lanka, with its long history of Indo-phobia, is well aware what a close relationship with the United States, may mean. Whilst during the armed conflict, military support was lent to Sri Lanka, post-conflict that has become more tempered. Indeed, Colombo is aware that US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo's outlined vision of “a free and open and prosperous Indo-Pacific… upholding the rules-based international order”, may mean the end Sinhala Buddhist ethnocracy on the island and a radical rethink of the structure of the Sri Lankan state itself. American support is only sought when it doesn't impinge on Sinhala chauvinism.

This desire to keep the US criticism at an arms-length was demonstrated by the frosty reception of US Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, who was greeted with Sinhala protests and a refusal by the Prime Minister to meet with him. It is further evidenced by Sri Lanka’s unease with the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue Alliance.

Pompeo’s visit stressed the importance of bilateral relations between the US and Sri Lanka, whilst also voicing concerns over China, describing it as a “predator”. Human rights were also given a courtesy mention, with the State Department warning that it was watching events on the island closely.

Sri Lankan officials had told the press prior to the State Department that it was “not for outsiders to tell Sri Lankans how to run their country”.

![]()

A vision of global leadership

An America leader with a genuine commitment to moral leadership and human rights may alarm Sri Lanka's war crimes accused regime. Earlier this year, during a 7-hour genocide denial strategy session, Sri Lankan diplomats remarked with relief that there was “little happening in the UN” but “took time to ponder about Samantha Power becoming the next Secretary of State under a Joe Biden administration in the United States”.

But if the Biden administration wishes to set out a new pathway in which they truly demonstrate moral leadership, it will not be through tokenistic acts but with tangible actions. Where the former administration was willing to at least place a travel ban on Sri Lanka’s army commander, Shavendra Silva, the new administration must go further.

During US Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo’s visit to Sri Lanka in October, many Tamils were disappointment by his silence on issues of human rights. Kumaravadivel Guruparan, the former Senior Lecturer in Law at the University of Jaffna, stated on Twitter "No symbolic reference to 'reconciliation' even, leave alone justice, accountability and a political solution."

He further added that

“We hope that the US will very closely watch the rapidly shrinking space for dissent, addressing human rights violations and the alarming level of involvement of the military in every aspect of civilian life”.

"America alone has the powers to find our disappeared children," said the Tamil families of the disappeared who tirelessly protested for over 1,347 days, demanding to know the fates of their loved ones. Many of whom have died without that condolence.

Tamils are counting on Biden and Harris for leadership. They must now deliver.