|

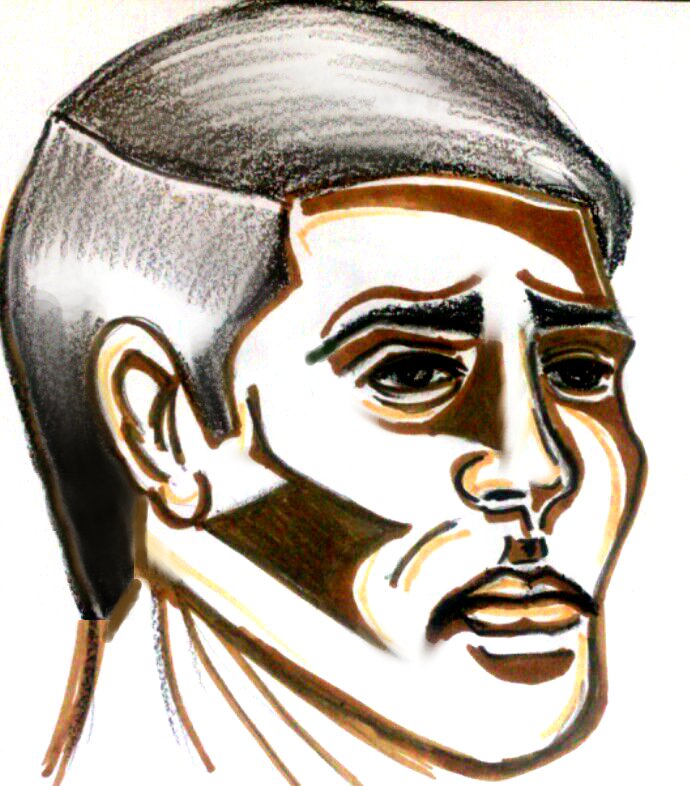

| Illustration Keera Ratnam |

The following account written by Paul M.M. Cooper is based on survivor interviews to Tamils Against Genocide (TAG). Personal details of Mayuran (not his real name), place names and dates have been changed to protect his identity.

Mayuran was in his mid-30s when the Sri Lankan army advanced into the LTTE-controlled North-East of Sri Lanka in its final assault. He first joined the LTTE when he was sixteen, and had been part of a team that laid claymore mines along enemy positions and also taught combat to new recruits. In Mayuran's own words, here is what he saw.

In 2009, when the Sri Lankan Army first declared its so-called “no-fire zones” people began to flock to these small areas in their tens of thousands as the shells began to fall all over landscape of mudflats and low jungle of the Vanni region.

Houses, bunkers, camps and refugee infrastructure were constantly hit in the wake of the Government offensive into the North. Soon, after the government had repeatedly hit the no-fire zones with barrages of artillery, rocket strikes and air strikes, the Tamil people of the North began to realise the pattern. There were no such things as safe-zones. The government knew the co-ordinates of them well, and were still striking them – and striking them hard.

The UN building was clearly marked and so were the hospitals. All were hit with artillery strikes. The Government knew the coordinates of all these buildings. Schools were repeatedly hit too, though most of these had been converted to hospitals by then.

People tried to leave in their thousands, but with the constant shelling and the rumours of Sri Lankan troops firing on civilians, nobody got very far. By the end of the war, which lasted 30 years, most families within the territory had at least one member in the LTTE. Parents and families couldn’t leave behind their children and relatives to seek shelter in Government-controlled areas. Everyone huddled together while the bombs fells all around.

Fear was everywhere. Towards the end, the Sri Lankan army began using weapons the LTTE had never seen before: weapons seen only in YouTube videos from Iraq and other war torn places, explosives that created huge smoke, flames and unusually loud booms.

Mayuran saw what he believes to this day to be chemical weapons used against civilians. The aftermath told it all: whole bodies charred and burned so as to be indistinguishable as human forms, and all the trees and sand around the blast radius burned, any plastic and clothes melted.

The navy was surrounding the area constantly with gunboats and patrol craft, encircling the area and preventing people from leaving by sea. As Mayuran fled the area before the Mullivaikal massacre began, he saw the Navy firing on and shelling those who were trying to flee by boat. The chaos and screaming, dead bodies floating in the sea.

Mayuran lost 10 family members in the war. When it ended, he fled, fearing for his life, and he sought political refuge in Britain. He gave a full account of his role in the war to the UK Border Agency, believing he had been right to join the LTTE. He did not wish to disown any of his actions. The Border Agency agreed that Mayuran would be persecuted by the government in Sri Lanka, but they said that he, by virtue of being a member of the LTTE, had committed war crimes, and would therefore not be allowed to live in Britain.

A British court rejected all allegations against Mayuran, deciding that his team had laid claymore mines in locations where enemy soldiers, and not civilians, would be injured. Although he had trained new recruits, when he found people under 18 wishing to join, he had refused to let them join. The whole time, he believed he was fighting on behalf of the Tamil people. The court said: "Undoubtedly there were human rights abuses committed by the LTTE but there is insufficient reason to connect all or any of them to this appellant."

Finally, Mayuran was allowed to stay.

This month marks the fifth anniversary of the end of the war in Sri Lanka. Mayuran’s story is also that of thousands of Tamils who witnessed Sri Lanka's Killing Fields

Say No to Genocide.

May 2009 profiles

Ainkaran

Ahalya