|

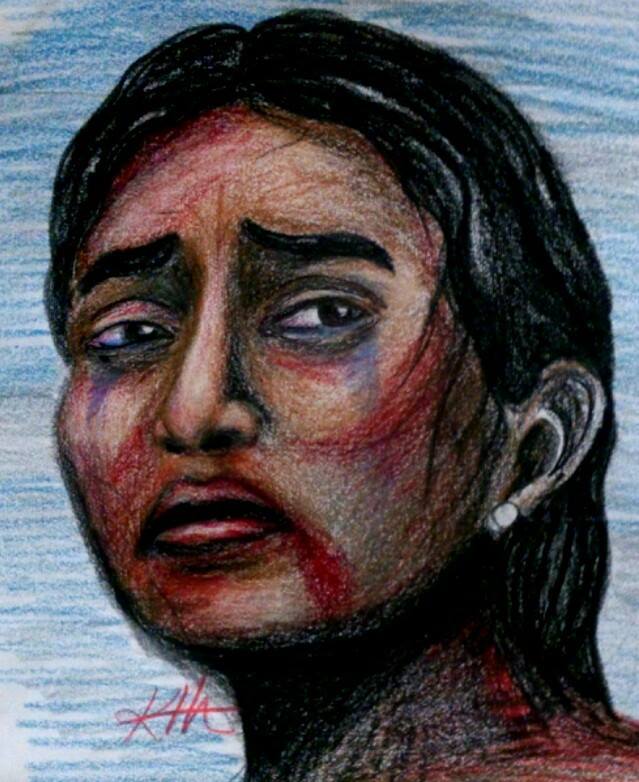

| Illustration by Keera Ratnam |

The following account written by Paul M.M. Cooper is based on a survivor interview to Tamils Against Genocide (TAG). Personal details of Ahalya (*not her real name) and her family members, place names and dates have been changed to protect their identities.

Ahalya was in her late twenties when the war in the Northeast of Sri Lanka came to an end. She was the sister of an LTTE fighter who was killed fighting in the war, and since his death had been determined to do what she could to alleviate the suffering of the Tamil-majority population of the LTTE-controlled zone.

During the war, Ahalya assisted in the hospital in Oru Kiraamam, while her mother and father stayed at home and looked after her little son. It was hard work, and at first dealing with the wounded and the sick made her heart tremble. She grew tougher, though, and before long her work at the hospital, along with caring for her child, became the focus of her life.

The Vithiyasaalai Hospital, like most institutions and public services in the North of Sri Lanka, was run by the LTTE. The hospital catered only for civilians, though. Even when the cadres of the LTTE came injured to the hospital in their camouflage fatigues, they were asked to change into civilian clothes, and they respected that rule. Medicine and other medical supplies were brought in by sea, on the outboard motors of the Sea Tigers, the naval wing of the LTTE, but such resources were scarce, and only growing scarcer.

As the Sri Lankan Army began its push into the North of the country in 2009, Ahalya and her colleagues began to worry about the medical supplies. Soon patients were going without the essentials: bandages, antibiotics, even painkillers. The hospital began admitting people it knew it didn’t have the resources to treat. The words on everyone’s lips were that the army was coming. By January, you could hear the sounds of artillery in the distance, like rolls of thunder.

Then a Sri Lankan Army shell hit the hospital, blowing out one wall and spattering shrapnel in all directions. You can still see the shrapnel scars on the hospital walls. After this all the doctors and nurses and patients were relocated by truck to Ennoru Kiraamam, a small village on the Indian Ocean coast. The Sri Lankan army had declared this a No Fire Zone. Ahalya went too, bringing her mother, father and her little son with her. Soon more refugees began to flock there.

At first there were enough medical supplies and food in Ennoru Kiraamam, but as the Sri Lankan Army advanced, supplies began to run low. Ahalya was afraid for her family: her mother, her father and her son. Then the shells began to fall without mercy.

Day and night, the explosions rocked the village. You could feel the shocks through the earth, hear the screams of the wounded, see the smoke rising through the trees. Despite being part of the No-Fire Zone, Ennoru Kiraamam was pounded mercilessly by artillery, rockets, and bombs dropped from the Sri Lankan Army’s Israeli-made Kaffir jets. Dead bodies were everywhere, with shards of shell stuck in their flesh.

There was absolute starvation. Children died of hunger. People wasted away. All day they stood in long, winding queues just to get a bowl of Kanji, a rice gruel that the LTTE served as a ration to the civilians in the area. The food queues were also bombed, killing countless people, but the yawning hunger in their bellies always drove them back to stand in line. The shelling took place without break from dawn to sunset. You never get used to it.

Then Ahalya’s mother was hit by a shell, and killed. She was buried nearby, without hesitation and without ceremony. Ahalya, her father and son couldn’t even go to see her body, as the shells were still falling. They wept in their tent, holding each other in their makeshift bunker as its walls and ceiling shook around them.

In Ennoru Kiraamam life was hard. The civilians were crowded into a church and a school next door that served as a temporary hospital. LTTE medical officers were serving there alongside government doctors. On the 21 April 2009, Ahalya was less than 100m away from the church, staying in her tent, when a bomb fell through the church roof and killed the 1,800 people inside in an instant.

After that, a lot of people tried to leave, but wherever they went, the shells were falling, bursting like seedpods. Nobody got very far into the dense jungle before coming back. The army had them surrounded on all sides. Behind them was the Indian Ocean, calm and blue as the bombs fell.

Ahalya slept on sarees and fertilizer sacks with her father and son. There was non-stop shelling. Sometimes she crept out of the bunker in the dark of night, unable to sleep, and found shell casings and bullets littered about the ground.

By 23 April, life in Ennoru Kiraamam had become impossible. Ahalya, who had watched her mother die, now saw that her little son was falling ill. She resolved to leave the “no-fire zone”, cross over into government-controlled territory and find help.

She left Ennoru Kiraamam with her father and son, three generations of the same family along with some neighbours. There was chaos, as they tried to leave. The Sri Lankan army advanced towards Ennoru Kiraamam. The sounds of gunfire, the smell of cordite. People wailing for help.

On the other side, they were rounded up and escorted south, where the army counted and registered them. She was forced to sign a document that was in Sinhala, a language she couldn’t read or speak.

Then Ahalya was taken to a camp, and separated from her son. There were more than 2,000 people there but she knew almost no one. She was questioned. When the government found out from others that her brother had been a soldier in the LTTE, her questionings became interrogations. She was kept in a single room, away from the other prisoners. There was only a small hole for light to come through and she tried to kill herself.

When she was finally released, she was told to report every two weeks to the police. But she was tortured when she did. Fearing for her safety she fled. As did her family. But they have not been able to be together. Ahalya has not seen her father and her son for longer than she can bear.

This month marks the fifth anniversary of the end of the war in Sri Lanka. Ahalya's story is also that of thousands of survivors of Sri Lanka's Killing Fields.

Say No to Genocide.

May 2009 profiles

We need your support

Sri Lanka is one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a journalist. Tamil journalists are particularly at threat, with at least 41 media workers known to have been killed by the Sri Lankan state or its paramilitaries during and after the armed conflict.

Despite the risks, our team on the ground remain committed to providing detailed and accurate reporting of developments in the Tamil homeland, across the island and around the world, as well as providing expert analysis and insight from the Tamil point of view

We need your support in keeping our journalism going. Support our work today.

For more ways to donate visit https://donate.tamilguardian.com.