The following account is based on interviews to Tamils Against Genocide. Personal details of Kumaran (not his real name), place names and dates have been changed to protect his identity.

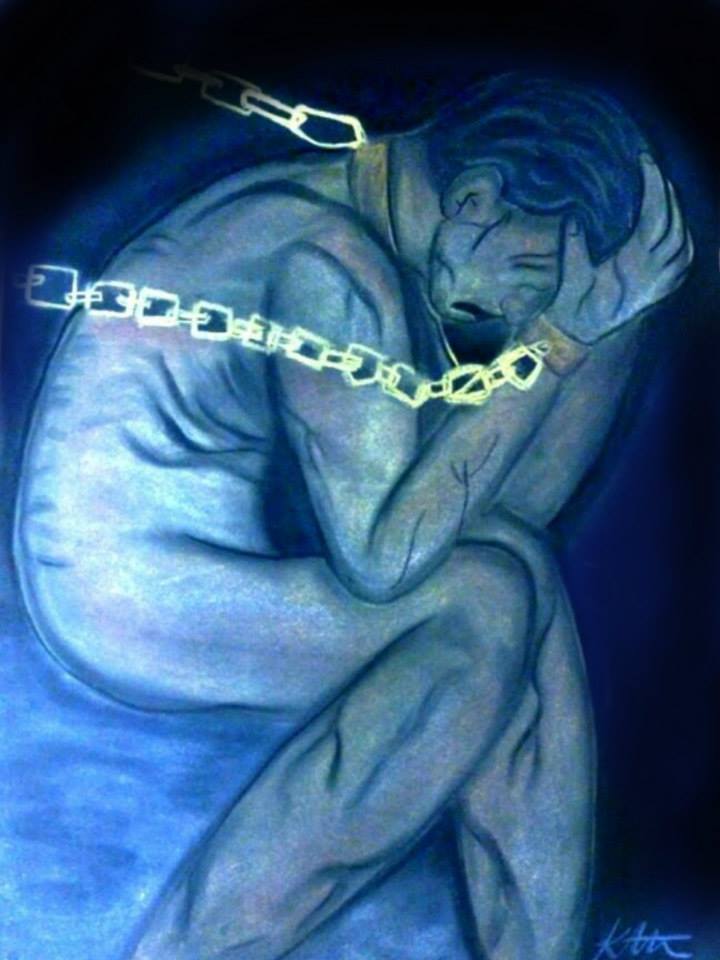

When Kumaran wakes up in the room he has been given by the Home Office, it takes him a few minutes to adjust to his present surroundings. Sleepless nights, recurrent nightmares and depression help contribute to this disorientation. He feels an overwhelming sense of claustrophobia, of the walls moving in, caging him once again. His room, his present day cage, reminds him of the cell he had been kept prisoner in for two years. It is difficult for him to differentiate between the nightmares of his sleep and his present reality. For Kumaran, life in his room in the UK is one of living torture: uncertainty and threat of deportation mirror the uncertainty and fear which shadowed him when locked away for so many months. For Kumaran the years ahead seem to hold nothing but ceaseless striving: to reconcile the trauma of his past with the relative security of his present.

Kumaran had been pressured into joining the LTTE by his friends and served with the group for eleven years until May 2009. After an initial training period, he worked first in the LTTE kitchens, providing food for the cadres. Later he worked in one of the LTTE hospitals at Puthukudiyirruppu, cooking and caring for injured LTTE members. By 2007 Kumaran had been transferred to the Administrative Service of the LTTE, interacting with civil society and visiting dignitaries. He continued to run his own bakery, providing food for the LTTE cadres.

During the final few months of the civil war, from January to May 2009, Kumaran manned food stations for the civilians in the No Fire Zone, serving rice porridge to people being starved and shelled by Sri Lankan forces. He served in various food stations around the No Fire Zone, on each, the colleagues he worked with were killed next to him as they handed out food to the people. He did not see his family during these months. He did not know whether they were alive or unharmed. His job was to provide for the suffering populace, and he did this, until the food ran out.

As the war drew to a close Kumaran witnessed many incidents of crimes against humanity perpetrated by the Sri Lankan army on the Tamil population herded into the No Fire Zone. He witnessed the deaths of young and old, at schools, makeshift hospitals and in bunkers. A pattern seemed to have been established. First spy planes would fly overhead, and then the shelling would begin. Kumaran served in food distribution centres in areas thick with civilians. One of the centres was set up next to a hospital, another by a library, another by a church. Each of these distribution centres would have been easily identifiable from the air: many had queues of civilians numbering in the hundreds. Kumaran and fellow LTTE members serving at these centres were dressed in civilian clothing. There was nothing to mark these places as posing a threat to the military, or of being of a combative nature. Yet each of the 4 food distribution centres Kumaran worked at were shelled by the Sri Lankan military leading to the death and injury of many civilians.

When Kumaran sought out his family in May 2009, he found the bunker in which they had been sheltering in the No Fire Zone had been shelled and had caved in. His wife’s legs had been burnt and she was severely traumatised. Her nephew had also been injured; her sister and parents had just been killed. Chaos, confusion and fear were pandemic among the people who were being mercilessly annihilated by cluster bombs, Kfir fighter planes and Sri Lankan naval vessels. Kumaran helped those around him, carrying the wounded to makeshift hospital stations, finding shelter for others, helping care for the civilians around him.

When Kumaran and his family surrendered to the Sri Lankan forces, along with the countless other civilians around him, he was taken to Omanthai. There the people were divided into three groups: LTTE members, those who had assisted the LTTE, and civilians. Fearing for his life, Kumaran and his family joined the group who had assisted the LTTE and they were sent to Anandakumaraswamy Camp.

For the next month Kumaran kept a low profile at the camp. Conditions were appalling: there was hardly any food or water, and the people survived by straining muddy water through clothes. It was on the 10th June 2009, when going to buy some biscuits for his young son from a newly set up Co-operative, that Kumaran was arrested by the police and the CID. In front of his son, he was blindfolded, his hands tied and he was bundled into a waiting white van. After a long drive, he was placed into a cell-like room. It was small, barely big enough to hold an adult, and it was dark. In the disorientating darkness, Kumaran could hear the sounds of people crying, of screams of pain. Cloaked in the dense darkness, Kumaran listened to the sounds of suffering which punctuated that long night. The next morning he was interrogated by the police and the CID, who knew that he had been a member of the LTTE. After a lengthy questioning he was asked to sign three documents written in Sinhalese, a language he was unfamiliar with. Kumaran refused to sign these documents. His refusal led to him being stripped naked, interrogated and videotaped repeatedly.

And then Kumaran became one of the disappeared.

This month marks the sixth anniversary of the end of the war in Sri Lanka. Kumaran’s story is also that of thousands of Tamils who witnessed Sri Lanka’s Killing Fields.

Say NO to Genocide.

May 2009 profiles

Theeban

Mayuran

Ainkaran

Ahalya

|

| Illustration Keera Ratnam |

When Kumaran wakes up in the room he has been given by the Home Office, it takes him a few minutes to adjust to his present surroundings. Sleepless nights, recurrent nightmares and depression help contribute to this disorientation. He feels an overwhelming sense of claustrophobia, of the walls moving in, caging him once again. His room, his present day cage, reminds him of the cell he had been kept prisoner in for two years. It is difficult for him to differentiate between the nightmares of his sleep and his present reality. For Kumaran, life in his room in the UK is one of living torture: uncertainty and threat of deportation mirror the uncertainty and fear which shadowed him when locked away for so many months. For Kumaran the years ahead seem to hold nothing but ceaseless striving: to reconcile the trauma of his past with the relative security of his present.

Kumaran had been pressured into joining the LTTE by his friends and served with the group for eleven years until May 2009. After an initial training period, he worked first in the LTTE kitchens, providing food for the cadres. Later he worked in one of the LTTE hospitals at Puthukudiyirruppu, cooking and caring for injured LTTE members. By 2007 Kumaran had been transferred to the Administrative Service of the LTTE, interacting with civil society and visiting dignitaries. He continued to run his own bakery, providing food for the LTTE cadres.

During the final few months of the civil war, from January to May 2009, Kumaran manned food stations for the civilians in the No Fire Zone, serving rice porridge to people being starved and shelled by Sri Lankan forces. He served in various food stations around the No Fire Zone, on each, the colleagues he worked with were killed next to him as they handed out food to the people. He did not see his family during these months. He did not know whether they were alive or unharmed. His job was to provide for the suffering populace, and he did this, until the food ran out.

As the war drew to a close Kumaran witnessed many incidents of crimes against humanity perpetrated by the Sri Lankan army on the Tamil population herded into the No Fire Zone. He witnessed the deaths of young and old, at schools, makeshift hospitals and in bunkers. A pattern seemed to have been established. First spy planes would fly overhead, and then the shelling would begin. Kumaran served in food distribution centres in areas thick with civilians. One of the centres was set up next to a hospital, another by a library, another by a church. Each of these distribution centres would have been easily identifiable from the air: many had queues of civilians numbering in the hundreds. Kumaran and fellow LTTE members serving at these centres were dressed in civilian clothing. There was nothing to mark these places as posing a threat to the military, or of being of a combative nature. Yet each of the 4 food distribution centres Kumaran worked at were shelled by the Sri Lankan military leading to the death and injury of many civilians.

When Kumaran sought out his family in May 2009, he found the bunker in which they had been sheltering in the No Fire Zone had been shelled and had caved in. His wife’s legs had been burnt and she was severely traumatised. Her nephew had also been injured; her sister and parents had just been killed. Chaos, confusion and fear were pandemic among the people who were being mercilessly annihilated by cluster bombs, Kfir fighter planes and Sri Lankan naval vessels. Kumaran helped those around him, carrying the wounded to makeshift hospital stations, finding shelter for others, helping care for the civilians around him.

When Kumaran and his family surrendered to the Sri Lankan forces, along with the countless other civilians around him, he was taken to Omanthai. There the people were divided into three groups: LTTE members, those who had assisted the LTTE, and civilians. Fearing for his life, Kumaran and his family joined the group who had assisted the LTTE and they were sent to Anandakumaraswamy Camp.

For the next month Kumaran kept a low profile at the camp. Conditions were appalling: there was hardly any food or water, and the people survived by straining muddy water through clothes. It was on the 10th June 2009, when going to buy some biscuits for his young son from a newly set up Co-operative, that Kumaran was arrested by the police and the CID. In front of his son, he was blindfolded, his hands tied and he was bundled into a waiting white van. After a long drive, he was placed into a cell-like room. It was small, barely big enough to hold an adult, and it was dark. In the disorientating darkness, Kumaran could hear the sounds of people crying, of screams of pain. Cloaked in the dense darkness, Kumaran listened to the sounds of suffering which punctuated that long night. The next morning he was interrogated by the police and the CID, who knew that he had been a member of the LTTE. After a lengthy questioning he was asked to sign three documents written in Sinhalese, a language he was unfamiliar with. Kumaran refused to sign these documents. His refusal led to him being stripped naked, interrogated and videotaped repeatedly.

And then Kumaran became one of the disappeared.

This month marks the sixth anniversary of the end of the war in Sri Lanka. Kumaran’s story is also that of thousands of Tamils who witnessed Sri Lanka’s Killing Fields.

Say NO to Genocide.

May 2009 profiles

Theeban

Mayuran

Ainkaran

Ahalya