Ilankai Tamil Arasu Kachchi (ITAK), the largest Tamil party in Sri Lanka and once a pioneer of Tamil nationalism in the first decades after the independence of Ceylon, has strayed far from its historic mission. Founded in 1949 as the Federal Party, ITAK was born out of the necessity to challenge the Sinhala-Buddhist majoritarianism that sought to dismantle the political and cultural identity of the Tamil people. Under leaders like S.J.V. Chelvanayakam, ITAK shaped the Eelam Tamil nation, spearheading the fight for self-determination and becoming a symbol of resistance against the Sri Lankan unitary state. In its early years, the party mobilised grassroots support and organised mass protests, most notably the 1961 Satyagraha campaigns against the Sinhala Only Act, which laid the path for a sustained movement demanding recognition and rights for the Tamil nation.

Satyagraha by Tamil women, Jaffna, 1961. Photograph Tamil Sangam

Yet, today, ITAK stands as a pale imitation of its former self. Its decision to decline the Tamil National People’s Front’s (TNPF) invitation in February to discuss steps towards a new constitution is a glaring example of its detachment from the Tamil struggle. By claiming the new government is “not ready” for constitutional changes, ITAK has chosen sluggish passiveness over principled leadership. This is not the ITAK that once mass-mobilised the Tamil people for protests against the Sinhala-Only Act or put forward pioneering ideas at their conventions; it is a party that has become a bystander in the fight for justice, equality and self-determination of the Tamil people.

Between 2015 and 2019, the Tamil National Alliance’s (TNA) collaboration with Ranil Wickremesinghe’s government marked a low point in the history of ITAK, which spearheaded the alliance. Since the Black July pogroms - supported by Ranil’s UNP, which has long compromised Tamil demands in favour of Sinhala-Buddhist interests - the Tamil people have been wary of his persona. Accordingly, the LTTE’s political advisor Anton Balasingham described him as a “sleazy fox”. Yet, ITAK and their TNA placed their trust in Ranil after the 2015 elections, where his victory was only possible by strategic Tamil votes aimed at preventing another Rajapakse reign - the architects behind the Mullivaikkal genocide and the post-war tyranny.

TNA/ITAK leader Sampanthan and Ranil Wickremesinghe waving the Sri Lankan flag together at a rally in Jaffna, 2012.

The TNA could have used its power as leverage against Ranil and made its support conditional on specific promises. But instead of advancing Tamil demands and fulfilling the mandate of their electorate, the ITAK lent legitimacy to a superficial reconciliation process that failed to address core issues like accountability for war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide, and meaningful devolution of power for a Tamil homeland. In a recent Al-Jazeera interview with Mehdi Hasan, Ranil’s true colours were on display: childish, arrogant responses to serious questions, and a blatant lack of political will to drive meaningful progress in Sri Lanka. The uncritical endorsement by ITAK not only bolstered the Ranil government’s empty promises but also provided Western states with the pretext to invest millions of dollars in a supposedly “reconciliatory” and “good governance” administration. In doing so, these states revealed either a naive hopefulness or a deliberate disregard for the enduring structures of Sinhala-Buddhist majoritarianism that Ranil continued to uphold. Fluent in the language of liberal democracy when speaking to international audiences, Ranil knew how he could use the TNA’s support to project himself as a moderate alternative to the Rajapaksas. Tamils who questioned this uncritical support were swiftly branded as “extremist” and “fringe” by both the TNA and the Colombo bubble, even though time has proven them right. By aligning with Colombo, ITAK betrayed the trust of the Tamil people, effectively becoming a tool of the very system it once wanted to dismantle.

The Tamil nation, which includes the electorate in the homeland but also their well-connected peers in the diaspora, watched this betrayal with growing frustration. While Tamil civil society and the diaspora continue to advocate for justice and self-determination, the Tamil nationalist political parties in Sri Lanka have retreated into political complacency. The only exemption was the TNPF, which has proven itself as a voice of principled Tamil positions in the past years, unafraid to challenge the Sinhala-Buddhist state and demanding the end of the unitary state structures. Despite their own failures at the 2024 elections, it is applaudable that the TNPF has realised its own mistakes in mobilising people and has therefore called for unity among the fragmented Tamil nationalist parties. The losses during the 2024 elections were a timely reminder of the need for a cohesive Tamil political front.

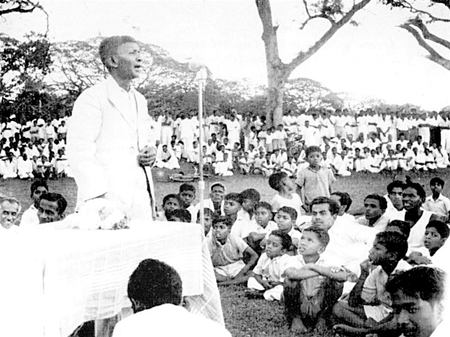

S.J.V Chelvanayakam, founder and leader of ITAK.

The internal divisions within the ITAK leadership further weaken its ability to represent Tamil interests. The criticism faced by some ITAK politicians for controversial remarks on the armed struggle and national symbols reflects a party that has lost its ideological clarity and is deeply divided in its leadership. Such discord only serves to undermine the Tamil struggle, leaving the community fragmented and vulnerable. It’s up to the principled grassroots members of ITAK to hold their leaders accountable and push the party back to a real Tamil nationalist path. Something they haven’t done so far, often staying quiet out of loyalty or fear of rocking the boat.

The rise of the National People’s Power (NPP) in Tamil-majority districts is a wake-up call for Tamil nationalist parties. While some longstanding critics of Tamil nationalism interpret this as a decline in Tamil nationalist support, it is more accurately a reflection of the Tamil electorate’s disillusionment with their traditional representatives. The enduring significance of Maaveerar Naal, the rejection of Sri Lanka’s Independence Day in the Tamil North-East, as well as continuing mass protests against state-sponsored Sinhalization and militarisation, underscores the Tamil people’s continued thirst for justice and self-determination. Already in the past, pro-Sri Lankan government party representatives have tried to use Tamil nationalist symbols in the North-East to mobilise electoral support. This year, the NPP campaign in Tamil areas used songs and speeches with references to the LTTE and Tamil nationalist symbols to show that they are not “hostile” towards the Tamil nationalist masses.

The upcoming local government and provincial council elections present a critical opportunity for Tamil nationalist parties to reclaim their historic role. By uniting around core demands - such as accountability, self-determination, and the rejection of the Sri Lankan unitary state’s structures - they can rekindle the trust of the Tamil electorate and challenge the majoritarian paradigm. Only a cohesive Tamil political front can effectively advocate for the rights and aspirations of the Tamil nation.

If ITAK continues to align with Colombo and dodge its responsibilities, it will be remembered not as a challenger but as a betrayer of the Tamil struggle. On the other hand, the Tamil people in general, in the occupied homeland and in the diaspora, have shown that the fight for justice and self-determination is far from over. It is time for Tamil nationalist parties to rise above their differences, embrace their historic mission, and stand united for the Tamil cause.

The Tamil nation deserves new leaders who are courageous, principled, and committed to the liberation struggle. Anything less is a betrayal of the struggle’s sacrifices and a disservice to the future of the Tamil people.