Amnesty International called on the international community to “urgently review cooperation with the Sri Lankan government” including the training and provision of its security forces, as it released a new report detailing how the military and police engaged in violent suppression of protests.

The newly launched report looked at 30 protests that took place on the island between March 2022 and June 2023, including in the Tamil North-East, and stated that the security forces must be held accountable for committing widespread human rights violations.

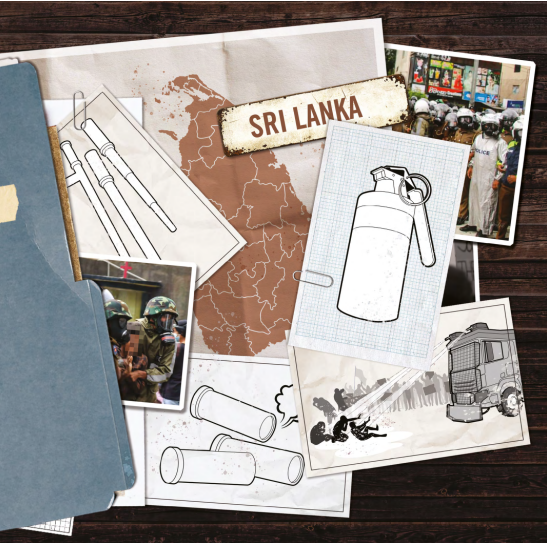

Amnesty International's research shows a pattern in the unlawful use of tear gas and water cannon and the misuse of batons by Sri Lankan law enforcement authorities with video evidence revealing that in at least 17 protests – more than half of the protests analysed – law enforcement fell well short of abiding by international law and standards.

In the Tamil North-East, where protests against Sri Lanka’s occupation regularly take place, Amnesty said the “security forces and intelligence agencies regularly carry out surveillance, intimidation, harassment, and obstruction of largely peaceful protests”.

Sri Lankan police fire a water cannon in Jaffna, 15 January 2023.

The human rights organisation examined a protest by Tamil families of the disappeared on 15 January 2023, where they protested against Sri Lankan president Ranil Wickremesinghe’s visit to Jaffna.

“Buses from Kilinochchi, Mullaitivu and Vavuniya carrying Tamil families of the disappeared traveling to the protest sites were stopped and questioned by the Sri Lankan police,” said the report. “They also took down the personal details of all the bus drivers and those on the buses.”

“Members of the STF and the police erected barricades to prevent the protesters from moving forwards. Subsequently, police used water cannon against largely peaceful protesters in the north for the first time in 2023.”

Devika, whose husband was forcibly disappeared 15 years ago after the end of the internal armed conflict, told Amnesty International,

“[President] Ranil said that those who are disappeared are dead some years ago and now he is coming to Jaffna to celebrate Pongal. We want answers about those who were disappeared.” She described being stopped by the police during the procession and getting caught between the barricades police had set up on the road. Afterwards, she said, “they suddenly used water cannon and kept changing the direction of the jets to target the protesters who were moving around. The jet came on my face, and I was hit badly in the eye. My eye swelled and I blacked out.”

“Water cannon in high pressure mode should only be used where there is widespread violence and violent individuals only cannot be targeted,” added Amnesty. “Water cannon can never be used to target the heads of protesters.”

Divya, whose son was also forcibly disappeared 15 years ago, told Amnesty International that, at the same protest on 15 January 2023:

“Police used water cannon directly at us. There was no warning, and the water was very hot. For the force of the jet my spectacles got thrown off my face. Their motive is to completely curb our protest. We have not celebrated anything in this house for 14 years; I look at the photo of my son on the phone and cry and ask him, where are you and why aren’t you looking for me?”

Anushka, another parent whose son was disappeared 15 years ago, after the end of the internal armed conflict, told Amnesty International:

“The Criminal Investigation Department officers are always at protest sites taking photos and videos of us and trying to stop us and ask questions. In January 2023, [at the protest] my hair was pulled, and I was pushed and manhandled. I was pushed around so much that I was caught between the iron barriers. There was no warning before the use of water cannon and the water was boiling hot. I wonder if something was mixed with the water because I was blinded and could not see. When the jets kept coming, I put my head down and was in so much pain when the jet hit my shoulders and back."

Lakshmi, whose husband was disappeared 15 years ago, told Amnesty International that, at many protests, police officers gather close to the protesters and prevented the media from recording harassment. She said:

“We only carried our phones, but they had their batons and pistols. The jets of the water cannon were so powerful that for 15-20 days after, I still had body pain. The water was hot. From 2009 we have had solid demands but there has been continuous surveillance and intimidation over the last 14 years. We are tired, getting weaker, mentally drained and feeling more hopeless.”

Kumanan, a prominent journalist from Mullaitivu, told Amnesty International:

“The military creates an environment at protest sites to frighten protesters. Media is not given free space to cover protests. Military, police, and intelligence disrupt media covering the protest; they take photos of media. Intelligence calls media to get information about protests. When there are human rights violations in the north and east and a complaint is raised, it is usually solved within the military and police itself – there is no proper procedure to move it to the next stage. In the east as well, they try to stop protests before they take place, with intimidation and suppression. There are informants set up within the community that pass on information to intelligence.”

“From the outset, the Sri Lankan police approached the 2022-23 protests assuming that they would be unlawful and violent and that they would need to use force to repress them,” said said Smriti Singh, Amnesty International’s Regional Director for South Asia. “The police failed to recognize that people have the right to peacefully protest and that the authorities have a duty to facilitate and protect protests. Instead, they targeted, chased, and beat largely peaceful protesters.”

Amnesty International wrote to the Sri Lanka police outlining the allegations in this report and requesting an official response but had not received a reply at the time of publication.

In its investigation the organisation found that the police followed a pattern of using large quantities of tear gas against peaceful or largely peaceful protesters repeatedly in the same area without giving them an adequate opportunity to disperse, and without making any reasonable effort to limit risk of injury.

In addition to this there was sufficient evidence police fired tear gas grenades from behind the protesters while the protesters were trying to disperse, in breach of international human rights standards.

“They also repeatedly failed to take adequate precautionary measures when using tear gas, and fired into areas that had no clear exit such as near schools and on the street. This unnecessarily exposed children and bystanders to the effects of chemical irritants. Amnesty International analysed at least three videos that showed children rubbing their eyes, coughing, and experiencing discomfort.”

Despite widespread human rights violations by law enforcement agencies and the security forces, not a single police officer or member of the army has been prosecuted or convicted for the unlawful use of force during protests in 2022 and 2023. This lack of accountability exists within the context of a wider culture of impunity, where police and military personnel have rarely been held accountable for human rights violations.

The report concludes by calling on the international community to “urgently review cooperation with the Sri Lankan government, including provision of training, law enforcement equipment and other security assistance to Sri Lanka law enforcement agencies, until officers responsible for unlawful use of force are thoroughly investigated and where appropriately brought to justice, robust accountability mechanisms are in place, and victims are entitled to obtain prompt reparation from the state including restitution, fair and adequate financial compensation and appropriate medical care and rehabilitation”.

The full report can be accessed here.