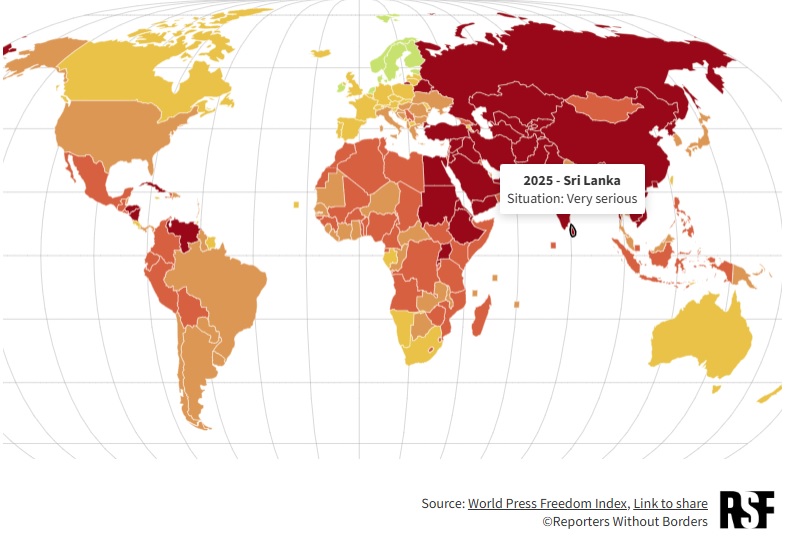

Sri Lanka has been ranked 139th out of 180 countries in the 2025 World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders (RSF), placing it among nations where journalism is considered “very serious” in terms of press freedom conditions.

This marks a modest improvement from its 2024 ranking of 150th, yet the country continues to face significant challenges in ensuring a free and independent media landscape.

RSF highlights that press freedom issues in Sri Lanka are closely tied to the legacy of armed conflict. The media landscape remains highly concentrated, with state-owned outlets dominating the sector. The Ministry of Mass Media oversees major media organisations such as the Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation (SLBC), the Rupavahini Corporation (SLRC), the Independent Television Network (ITN), and the Associated Newspapers of Ceylon Limited (ANCL).

The concentration of media ownership is further exemplified by the fact that the four largest newspaper owners control three-quarters of the country's readership. The main press group, Lake House, owned by the Wijewardene family, alone owns more than half of the country's publications. An RSF study concluded that fewer than one in five Sri Lankan citizens have access to politically independent media.

While Sri Lankan law does not explicitly restrict freedom of expression, there are no guarantees for the protection of journalists. The 1973 law establishing the Press Council allows the president to appoint most of its members, posing a significant problem for media regulation. Additionally, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) Act has been used to silence dissenting voices, and the Prevention of Terrorism Act is often employed to suppress journalists, particularly those investigating the living conditions of the Tamil minority in the north and east.

In January 2024, Parliament passed an internet regulation law creating the Online Safety Commission, whose members are appointed by the president. Under the guise of defending “national security,” this commission can censor content and accounts of dissident voices on social media and suspend the confidentiality of their sources.

The Sri Lankan media predominantly caters to the Sinhalese and Buddhist majority, making open criticism of the Buddhist religion or its clergy highly dangerous, said RSF. Prosecutors have previously used the penal code to imprison journalists on suspicion of religious hatred. Reporting on issues involving the Tamils or Muslims remains extremely sensitive, with journalists and media outlets facing arrests, death threats, and coordinated cyber-attacks.

Although no journalist has been killed since 2015, the previous killings have gone completely unpunished. The tenth anniversary of the end of the armed conflict in 2019 was marked by a troubling increase in attacks on reporters based in North-East, the traditional Tamil homeland. Journalists in these regions are subjected to systematic surveillance and harassment by the police and army.

See more from RSF here.