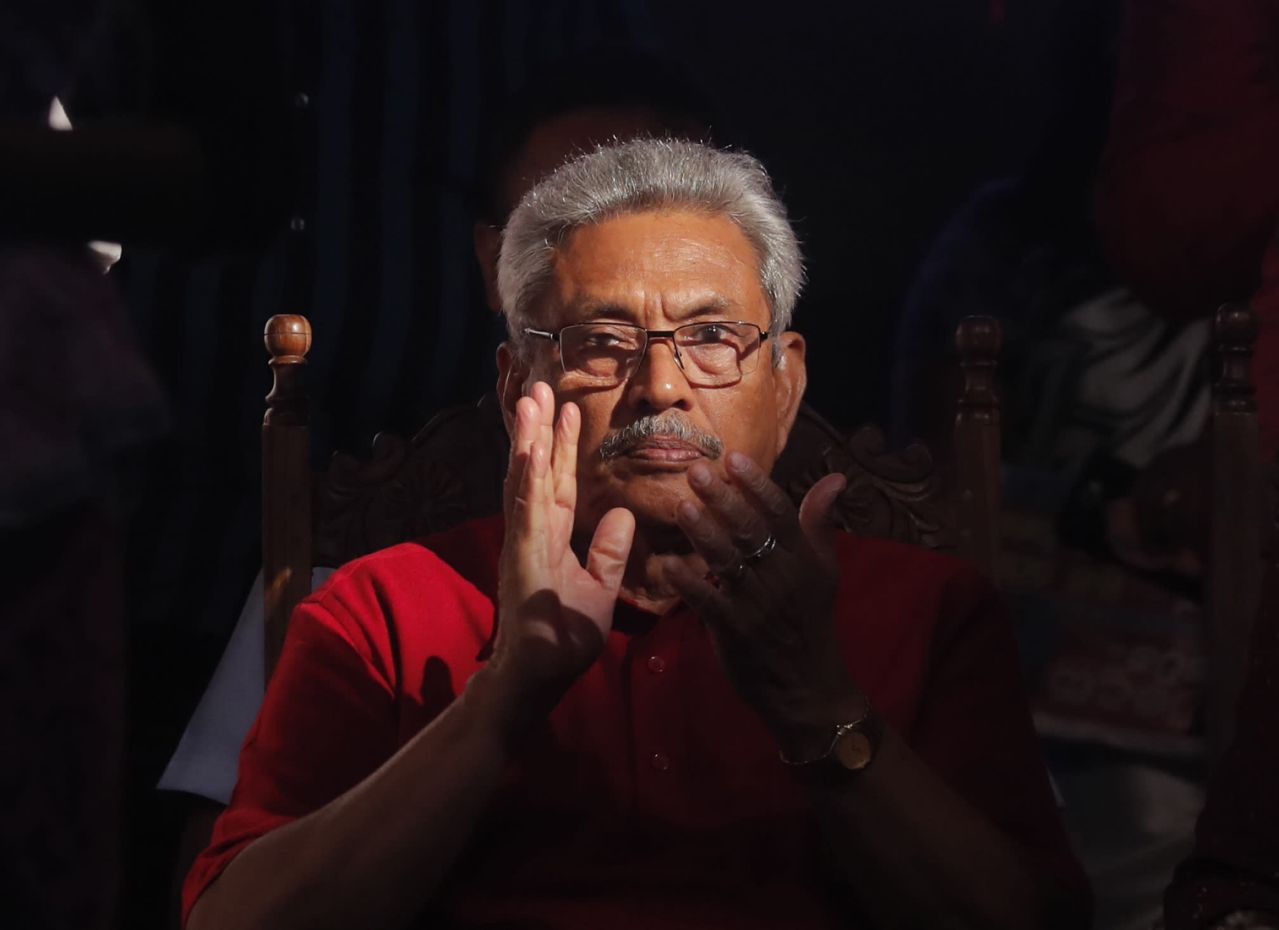

Writing in Middle East Eye, Strategic Advisor to People for Equality and Relief in Sri Lanka (PEARL), Mario Arulthas highlights the deterioration of Tamil and Muslim rights in Sri Lanka as President Rajapaksa appears “committed to seizing any opportunity to hurt non-Sinhalese communities”.

In his piece, he draws particular attention to Islamophobic legislation proposed to ban Islamic face coverings and close over 1,000 Islamic schools, under “national security” concerns. These moves he notes follow a long history in which the Sri Lankan state has “used laws to marginalise vulnerable communities […] to oppress Tamils and Muslims while strengthening the majoritarian ethnocracy that has dominated the country since shortly after its independence in 1948”.

Sinhala Buddhist nationalism

Reflecting on the roots of Sri Lanka’s ethno-nationalist ideology, he notes that Buddhism has been consistently promoted to the detriment of other communities. In doing so, Sinhalese scriptures presented other communities as invaders, “who either didn’t belong or were there at the benevolence of the majority”. This was codified under the country’s constitutes which maintained that it was the state’s responsibility to “protect and foster” Buddhism.

The enshrining of a Sinhala Buddhist into legislation arose alongside targeted violence against Tamils in the form of pogroms in which thousands were killed and Tamil homes and businesses were burnt to the ground.

As Tamil peaceful demonstrations in the 1960s and 1970s were meet with violence, there was an increasing disillusionment with the Sri Lanka state and demand for a separate Tamil homeland.

The state responded harshly with a brutal crackdown and the passage of the draconian Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) which granted security forces and the judiciary wide-ranging powers. Tamil youth were arrested en mass, tortured and many forcibly disappeared. It was this brutality that led many Tamils to grant support to militancy and which led to an all-out war with Sri Lanka’s military.

Despite calls from human rights organisations since the 1980s to repeal this legislation, the current regime has not only disregarded those demands but actively expanded the bill.

Arulthas highlights that the struggle against Eelam Tamils was particularly important as “Tamils native to Sri Lanka are also known, had a distinct identity and the concept of a historic homeland in the island’s northeast, which was at odds with what the [Sinhalese] majority envisaged”.

He further notes that:

“The common Tamil view of this situation as a genocide stems from the belief that the Sri Lankan state’s intent is to dismantle the Tamil identity and subsume it within a primarily Sinhalese-Buddhist Sri Lankan national identity, in which other communities play a subordinate role”.

This conflict has not ended as the state continues to oppress Tamils through the suffocating militarisation of the northeast. However, it has also their eyes on their Muslim minority.

“After the perceived vanquishing of the Tamils, Sri Lanka was in need of a new enemy. Islamophobia became commonplace, escalating into violence targeting Muslims and their businesses. The state took no action against perpetrators, and anti-Muslim campaigns, often led by Buddhist monks, proliferated” Arulthas notes.

Wanton cruelty

Highlighting the cruelty of the administration, Arulthas details a litany of abuses the Rajapaksa regime has engaged within since coming to power. From forced cremations, the destruction of a Tamil memorial, and expansion of the PTA.

He critiques the failure of the international community noting that the greatest opportunity for repeal was under the previous administration “but instead of holding Sri Lanka to its commitment to do so, the US and the EU prematurely rewarded Sri Lanka with increased political, trade and military links, reinforcing the ethnocratic structures that are so easily leveraged against minority communities”.

Despite the increased violence against Tamils and Muslims, he highlights that “the EU has just agreed to fund capacity-building for Sri Lanka’s counterterrorism efforts and its war crimes-accused security forces, together with the UN and Interpol, in a project worth $5m”.

International Pressure

Reflecting on the passage of the UNHRC resolution, he highlights the lack of political will in Sri Lanka to deal domestically with crimes that occurred. He also notes that whilst the efforts of the UNHRC are useful for leverage they are limited by institutional constraints.

He warns against over-reliance on the council and calls on individual countries “to use their own bilateral relationships in ways that give Sri Lanka limited options, other than to address longstanding grievances”.

He maintains that “in parallel, international efforts have to get underway to address international crimes”.

“If Sri Lanka is allowed to continue to go down the path it’s going, its future will look remarkably like its past”, he warns.

Read more here