|

The report by the UN expert panel on the final months of Sri Lanka’s war sets out a harrowing account of government forces’ conduct. Hundreds of thousands of Tamil civilians were subject to targeted mass bombardment, starvation and denial of medical assistance, resulting in tens of thousands of casualties and widespread suffering.

Extracts of the UN report leaked to the Sri Lankan press have, quite rightly, caused shock and prompted press coverage and commentary across the world along with renewed calls for an independent, international investigation.

In Sri Lanka, however, reaction has, predictably, been quite different: the report by respected international experts has been met with denial, dismissal and defiance by President Mahinda Rajapaksa’s government. Crucially, moreover, this categorical rejection and indignation is echoed across the Sinhala polity.

Instead of supporting international calls for a proper investigation and the prosecution of those responsible for mass atrocities against what are – supposedly – fellow citizens Sri Lanka’s mainstream media, commentators and, now, the main opposition parties have instead rallied to defend the regime and its conduct of the war. (The only exception, also predictably, is the Tamil National Alliance (TNA), the main Tamil political party, which has welcomed the report and its recommendations.)

The Sinhala nation has effectively closed ranks to defend its government and armed forces. This collective refusal to even countenance investigation of the state’s war crimes not only vindicates the call for an international inquiry, it also highlights the fundamental and enduring ethnic crisis in Sri Lanka.

Popular chauvunism

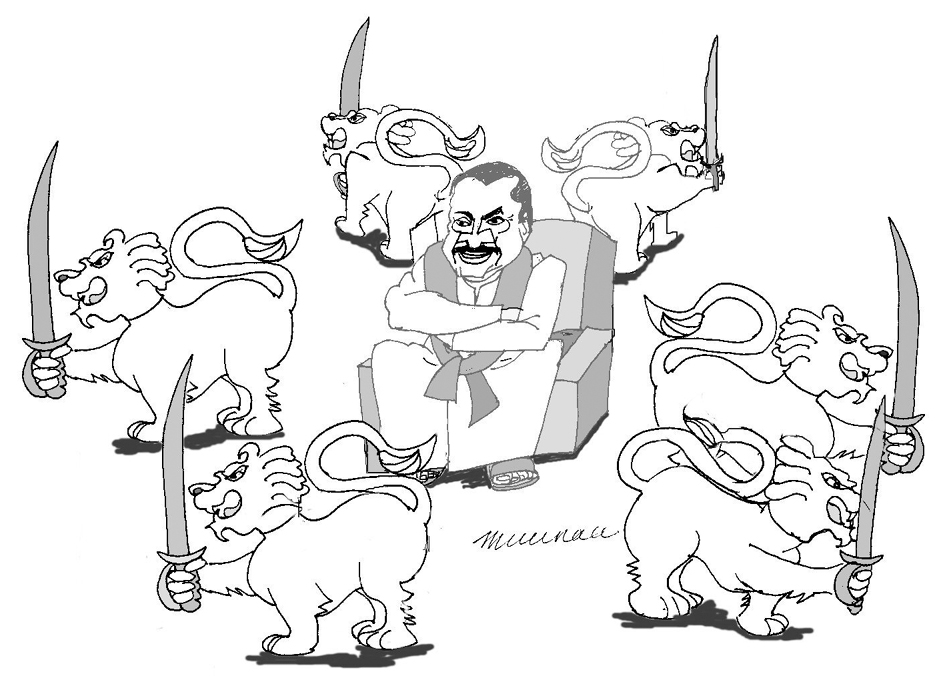

That the Rajapaksa regime represses dissent amongst the Sinhalese, quite separately from its chauvinist policies towards the Tamils, does not mean it does not enjoy considerable support for the latter. This is why, from the outset, the regime has been able to thumb its nose at international order and continue its persecution – which is how the UN panel also sees Colombo’s treatment of Tamils.

From the moment the UN panel was set up in mid 2010, the Sinhala nation's collective charge was that any such independent study was going to be false and biased. The largely Sinhala-owned independent press gleefully repeated in its editorial columns and commentary the state's claims of Western imperialism, threats to national sovereignty, and even a supposed international envy of Sinhala military’s success. Moreover, the press’s commentary has been routinely echoed by the vast majority of (Sinhala) readers’ in letters and feedback posts.

And last week, even before extracts of the UN report appeared in newspapers, the public denouncement had already begun. The state derided the report as 'fundamentally flawed’, to be ‘without any verification’, and to have used ‘patently biased material’. These sweeping statements have been repeated every time the state is presented with further evidence of state atrocities.

United voice

Yet each time, the Sinhala press have been eager, without any critical questioning whatsoever, to reproduce such statements as authoritative facts. The statements of doctors who served in the former warzone, the horrific videos of summary executions, and the accounts of the shattered survivors have been ritually dismissed as ‘fake’ or even serving some separatist agenda.

The Island newspaper which first leaked an extract of the report accompanied it Saturday with an editorial that embarked on a shamelessly personalized attack on the UN panel members. It accused the experts of self-serving partiality, whilst it defended the government. (Interestingly, a couple of days later, as the international significance of the UN report dawned, the paper changed its tact; an editorial admitting that crimes may have been committed, but only as a consequence of ‘terrorism’, and argued Sri Lanka must be given the chance to reform in its own time.

Other independent newspapers also rejected the report wholesale and attacked its supposed sponsors – the US, UK and UN (It is now customary to rail against abuses in Iraq and Afghanistan - that numerous trials are underway in both countries, and convictions are resulting is conveniently left out). The Sri Lankan newspapers have even resorted to praising the supposedly 'charitable' activities of the armed forces. The Sunday Times called for a popular referendum to give the UN a 'proper rebuttal'.

National solidarity

What is partiularly telling, however, is the reaction of the main Sinhala political parties. Despite the ample ammunition the UN report provides Sri Lanka’s opposition, instead of seizing the opportunity to challenge the government, the UNP and the JVP have instead rallied to Rajapaksa regime. Having chided the government for engaging with the UN panel at all, the two parties have renewed calls for a total rejection of the report.

"This is not a time to accuse each other as it is the duty of the government and the opposition to maintain the independence and stability of our country," the UNP's deputy leader Sajith Premadasa argued. The aligning of the UNP and JVP with the ruling SLFP represents a united front against accountability for state war crimes that almost entirely encompasses the Sinhala nation's collective mandate.

This is not the first time the state and the media have incited uprising against the UN and the West. Over the last two years, Sinhalese have loyally turned up in large numbers to burn effigies of western diplomats and blockade UN buildings, all in aid of preventing a war crimes inquiry. That the UN has already warned Colombo its offices must be protected at all costs underlines the widely recognised dynamics in Sri Lanka. This week President Rajapaksa has called for the forthcoming May Day rally to be one of united opposition to the UN and the international community.

The Sinhala polity’s collective opposition to investigating atrocities against Tamils is not new. Since independence in 1948, after every anti-Tamil riot, the Sinhala nation has applauded the perpetrators and repeatedly rejected the victims’ claims for justice and redress. Moreover, the Sinhala majority has consistently re-elected such perpetrators to office.

The mass atrocities in the Vanni is not one man’s work, nor indeed one government cabinet’s. Conducting an orchestrated massacre on this scale, and escaping any consequences, requires the collaboration of all main political parties and the country’s press. This has been reliably forthcoming under the banner of Sinhala-Buddhist supremacy and the bedrock of majority popular support.

Accountability for war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide has emerged in the past two decades as a key international norm. So has the idea of liberal democracy as the basis for any stable national politics. The pursuit of the former in the Sri Lankan case will inevitably take place against an emerging international recognition that the latter is nigh impossible.