Tamil families of the disappeared rallied in Kilinochchi and Vavuniya yesterday to mark 2,000 days of continuous roadside protest as the search for their forcibly disappeared loved ones continues.

In February 2017, Tamil families of the disappeared launched their roadside protests in Kilinochchi, followed by Vavuniya, Trincomalee, Mullaitivu and Maruthankerny. The families have spent years, in some cases decades, searching for their loved ones who were either abducted or handed over to the Sri Lankan military at the end of the armed conflict in 2009, on the premise that they would be returned.

Since their campaign for justice began, the families have maintained a set of simple demands:

1. Release a list of surrendees from the final phase of the armed conflict;

2. Investigate and release the list of all past and present secret detention centres;

3. Release the yearly lists of detainees under the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) since 1978;

2,000 days on, their demands and their vigour for justice remains the same.

Appeals to the international community

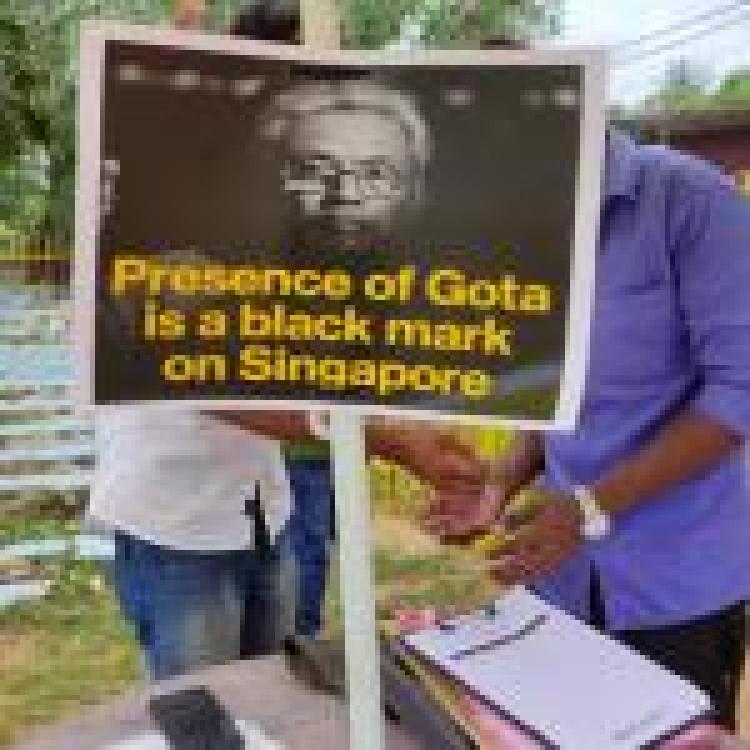

Misled by successive Sri Lankan governments and failed state-led commissions, the families have appealed to the international community for justice. The families have rejected domestic mechanisms such as the Office of Missing Persons (OMP) for lacking independence and have not held any of the perpetrators accountable. Despite the lack of progress made by the OMP, Sri Lanka continues to suggest to the international community that justice and accountability can be achieved domestically.

Speaking to journalists at the protest in Vavuniya, Cassipillai Jayavanitha said:

"We've been protesting for 2,000 days but we still do not have any answers. We know this government will not give us any answers, that's why we are appealing to the international community...If the government doesn't understand our struggle after 2,000 days then the international community must step in."

Surveillance and harassment

The Tamil families of the disappeared have faced surveillance and harassment by Sri Lanka’s security forces in an attempt to silence their pursuit of justice. In a briefing, Adayaalam Centre for Policy and Research (ACPR) highlighted that the protesters encounter “severe threats and harassment” while “some of the leading protestors are under constant surveillance.”

Earlier this year, the co-ordinator of the Mullaitivu Disappeared Relatives' Association, Mariyasuresh Eswari, was admitted to hospital with injuries after Sri Lankan police officers pushed her during a protest against former prime minister Mahinda Rajapaksa’s visit to Jaffna.

In spite of the violence and surveillance, the protesters have been relentless in demanding information on the whereabouts of their loved ones and an international justice mechanism.

Justice denied

Many of the parents who have been participating in the roadside protests are elderly and vulnerable. Since the beginning of the protests, 138 parents have passed away without knowing the truth about their disappeared children.