|

Sri Lanka’s trade, currency and debt quandary

The International Monetary Fund suspended its programme of supplying Colombo with credit in exchange for reform on Monday after Sri Lanka refused to follow advice and abandon a policy of actively intervening in foreign exchange markets to support the value of the Rupee.

Earlier this month Brian Aitken, the IMF’s head of mission in Colombo, warned that Sri Lanka’s policy of selling dollars to maintain the value of the rupee “does not seem to be in line with the fundamentals in the economy”’ and that the policy was rapidly depleting foreign currency reserves.

He pointed out that Colombo’s “non-borrowed reserves.. have steadily declined, reflecting foreign exchange sales by the central bank.”

(See Reuters' report here).

In July alone the central bank sold $416 million to support the value of the SLR against the US$ and is estimated to have sold over $300 million in August. (See LBO's report here).

Although the Central Bank claims that it holds $8 billion in reserves, most of this is in the form of loans: Sri Lanka actually only owns $700 million of reserves.

This is even lower than the $900 million Sri Lanka held in June 2009 when the war ended and it was forced to seek an IMF bailout in order to avoid defaulting on foreign loan repayments.

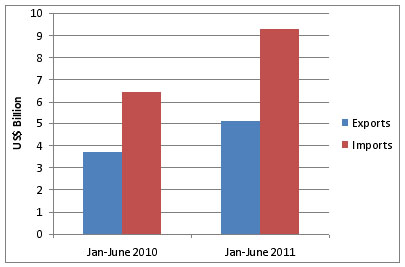

Expanding trade deficit

|

Sri Lanka’s trade deficit expanded a staggering 62 percent in the first half of this year compared to the same period last year, reaching $4.2 billion.

Against the IMF’s criticism, Sri Lanka’s Central Bank governor Ajith Cabraal, on Monday defended the policy of selling dollars to maintain the value of the rupee. Cabraal petulantly added that while Sri Lanka would take all advice, it would nevertheless steer its own path.

Analysts said that surging import demand was being fuelled by credit growth as Colombo used its growing control over the banking sector to fund government debt whilst also increasing credit to the private sector, thereby generating import demand.

Central Bank figures at the end of June showed that total bank lending increased by 29 percent between January and July, and in the same time banking lending to the government expanded 28 percent. (See p9 of this report).

(On a related theme, see also our earlier post on the links between bank lending and ethnicity in Sri Lanka).

Bank nationalisation by stealth?

Over the past few months Colombo has actively expanded its control over the banking sector by using state owned pension and insurance funds to buy shares in commercially owned banks. (See comments by opposition lawmaker Eran Wickramaratne here).

IMF mission chief Aitken has warned that Colombo’s use of state owned pension funds was undermining private sector confidence.

In loaded, if diplomatic language he said Colombo’s actions could be “misconstrued” and raised the potential for “negative perceptions” – meaning the government’s actions appeared to be nationalisation by stealth.

As such, Aitkin advised, “it may be good for the government to make its intentions clear and this would be better for private sector investor confidence.”

|

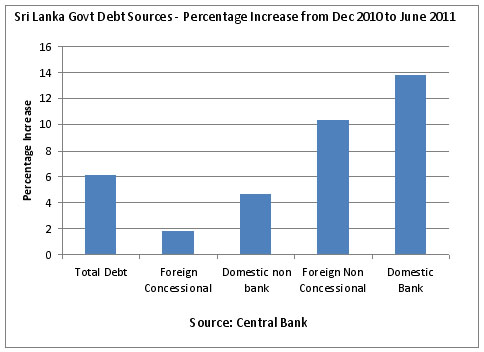

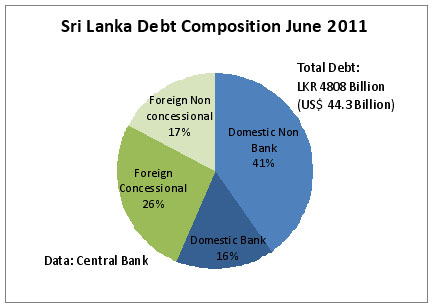

Foreign commercial (or non concessional) lending to the government also grew to 10 percent – making it even more critical for Colombo to maintain adequate foreign currency reserves to repay this foreign debt.

As an example of concessionary lending to the state, the Commercial bank has a loan of Rs 1.5 billion for the state run Road Development Authority (RDA), the Sunday Times reported.

The loan is payable over an extended period of fourteen and a half years while the terms of interest are unclear.

Sri Lanka has a long history of using its nationalised banks to provide cheap loans to Sinhala farmers and business as well as for welfare projects, such as housing construction that almost always benefit the Sinhala areas. Such loans are rarely ever repaid.

Earlier this month, the IMF formally noted the expanding credit, cautioning:

“Banks and other financial institutions should also guard against a relaxation of lending standards and the accompanying risk of a build-up of nonperforming loans.”

Why manipulate rates?

Although it is normal practice for banks to lend to governments, as most government debt produces safe returns, in Sri Lanka the state-linked banks are being directed to buy government debt at concessionary interest rates.

Ideally, the interest on government debt should be set by the market – i.e. the rates at which lenders are willing to risk their capital (lower interest rates indicating lower risk).

In Sri Lanka, however, the government is setting the interest rate of its debt at artificially low levels through Central Bank intervention and by directing state-linked (‘captive sources’) banks, pension and insurance funds to lend at cheap rates.

(See reports here, here and here).

|

So, if Colombo were to allow the exchange rate to rise, it would not only make imports more expensive, individuals and government agencies would use their borrowed cash either for domestic (rather than imported) purchases or, more likely, would not want to borrow as much.

As a consequence, in theory, import demand would fall and credit growth would slow.

But Sri Lanka has a problem: the economy simply doesn’t produce enough domestically, including sufficient food products, for example. (This is, incidentally, despite the heavy government subsidies to Sinhala farmers.)

Consequently, as the LBO analysis points out, Colombo wants to maintain both the exchange rate at a high value (enabling cheaper imports) and keep interest rates down (to allow it to continue borrowing at will).

(See LBO's analysis on the problems of the ‘soft peg’ here and here)

The effect of an overvalued rupee and unnaturally low interests is to produce both inflation and pressure on the currency to devalue.

Magic cycle

Colombo’s manipulation of the banking sector is further confounded by certain activities of the Central Bank.

As Sri Lanka’s banks run down their reserves of cash by lending at concessionary rates, the Central Bank has stepped in to maintain bank reserves by buying government debt held by banks in exchange for cash - cash that it simply prints at will (i.e. without underlying value).

In effect, the government borrows from the bank, and then the Central Bank prints rupees to ‘pay off’ the debt.

The banks are then encouraged to lend their newly printed cash at concessionary rates again, and thus the cycle repeats.

This expansion of money in the economy, without an increase in productivity, (which is what printing money means) has led directly to soaring prices on the street (inflation).

The government’s own preferred index is recording an inflation rate of 8.9 per cent, high by any standards. However, the LBO noted that the alternative wholesale price index has recorded an increase of 20 percent, a figure more in keeping with the soaring cost of living actually felt by ordinary people.

Exchange rate pressure

Meanwhile, government agencies - and those private consumers able to borrow - use cheap loans from state-linked banks to purchase even more imports, leading to pressure on Sri Lanka’s rupee to devalue.

The recent loan to the Road Development Authority, for example, will be used to purchase equipment and raw materials, much of it imported. (The percentage taken as graft by contractors, bureaucrats and ministers will also inevitably be used to buy luxury imports).

Foreign vendors have cottoned on to this. For example, in recent months, both Porsche and Range Rover have rushed to make their latest models available to Sri Lanka’s wealthy.

Meanwhile labourers hired to work on RDA and other government projects will likely spend their wages on food, much of it again imported.

For an import dependent and debt laden country like Sri Lanka, a weak currency is a problem. Not only does it increase the cost of essential commodities, such as oil, but a devalued currency would also make international debt repayments more expensive.

The government’s deliberate and repeated efforts to compel the domestic banking sector to fund its own shortfalls are thus having predictable consequences: fuelling inflation whilst also creating the conditions for yet another foreign exchange crisis.

And all good things eventually come to an end.