When you see me, what do you see first?

Is it my skin colour, my transness, or the occasional person next to me with whom my mouth and hands might be intertwined? But do you see: Eelam Tamil. Non-binary. Pansexual? Or: Non-binary. Pansexual. Eelam Tamil? Or even: Non-binary. Eelam Tamil. Pansexual? Semantics to some but in reality, it’s a political statement much like virtually every-single-thing else in this world. To me, these identities are not mutually exclusive. Those words exist in each other, and I exist as all three. This is my truth.

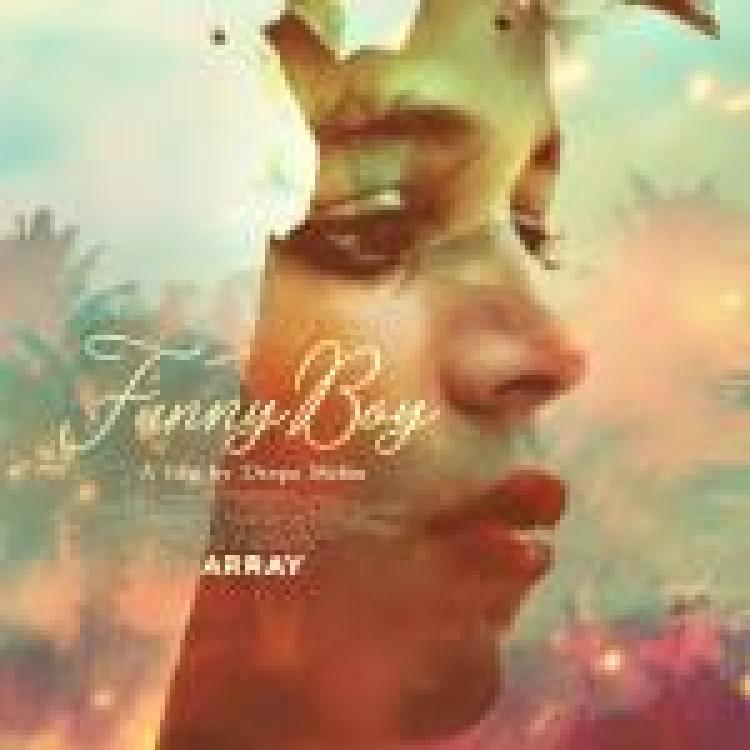

Funny Boy was my only hope at being seen as at least two out of the three, an explicitly queer Eelam Tamil whose only mistake was loving. Arjie was me, I am Arjie. Both of us, struggling to come to terms with who we are but also wanting to honour the struggles our families face. Both my parents fled Sri Lanka at the time this film was set in - the Black July pogroms of 1983 - leaving behind the ghosts of family members both murdered and disappeared. But all that is left in me is rage and a thirst for blood that I never knew I had. I have not come out to my parents - my queer existence remains solely online and in the hearts of my friends - but I thought Funny Boy would be the film I would show them when I eventually did. Instead, what I have been left with is an unholy alliance of historical inaccuracy and brutalisation of the Tamil language.

To have to watch Sinhalese and North Indians, people who have perpetrated cultural genocide of Eelam Tamils play them in a story centring Tamils, is a level of trauma to which I do not want to subject myself or my parents. If we all lived by Deepa Mehta’s worldview where we all suffer the same oppression by virtue of our brownness, the rape and murder of Tamils by Indian Peacekeeping Forces would never have happened, let alone the genocide of Tamils by the Sinhalese.

After this film became public knowledge, there was a lot of silence and an abandonment I frankly expected. I’m thankful for the likes of Sinthujan Varatharajah, Sunthar Vykunthanathan and the Queer Tamil Collective for the work they have done in protest of Funny Boy as queer members of the Eelam Tamil community. Having said that, these voices were often sidelined as people began to voice their concerns despite this being primarily a queer Tamil issue - perhaps a trivial detail to some, but crucial to those of the community most affected. Even then, often some of those who spoke of their concerns were too late, disappointingly ignoring calls for a boycott only to later concede that the film was harmful. Funny Boy is supposed to be a queer coming of age film, yet, our queer voices were not worthy enough to heed in the first place. This speaks profoundly to how we are seen, even to the most progressive within our community.

Given that even mainstream Eelam Tamil history has been under attack for so long, the burning of the Jaffna Public Library a stark illustration, those of us at the margins are even more defenceless against erasure. I have no queer ancestors to turn to - no Eelam Tamil ancestors to turn to full stop - because their memories have been systematically wiped out. Let’s not forget that although white people now have a monopoly on queer culture, the history of colonialism is also a history of criminalising queerness. So now, through violent colonisation both historic and ongoing, the only choices I have to understand my queerness are through a white supremacist lens or through an Indian Tamil one, neither of which I can really identify with. I am probably the only queer Eelam Tamil I know intimately and I have searched for others but, in public, we are few and far between.

Funny Boy the film came out in Canada on December 4th and it’s global release was on December 10th, less than two weeks after Maaveerar Naal. We were at a point of mourning and remembering our past, and resisting and organising against the repression of the present day. It was a moment where the community was coming together to learn about our struggle and how we could move forward in the name of Eelam Tamil liberation. But it was also a period where I wondered where I fit, in this liberation as a queer person. It is a question I’m sure every one of us queer Eelam Tamils have asked. What does liberation truly mean to you? Will it be another platform for cishet upper caste men to police the rest of our community? What does it mean to be Tamil? I hope the answers we reach stretch outside of the colonised confines that we are used to, shedding our casteism, anti-blackness and queerphobia, and working towards true liberation and justice.

But before I conclude my letter I invite you to reflect further with me: What will it take to be loved and recognised by you in my entirety? When will you scream the pain I scream as if it were your own? When will you and I know what it’s like to be truly free? Will you be there with me through it all? Because I will and your freedom as well as mine is all I yearn for. Sometimes the hardest thing to do is convince others of your humanity, yet here I am, writing for your acceptance and advocacy. Include me in your liberation for Tamil Eelam.

Please sign the petition by the Queer Tamil Collective and boycott Funny Boy. If not any of the above, at least do this.

V. Ravichandran is a writer interested in human rights, and a student of Physics at Imperial College, London.

Artwork also by V. Ravichandran.