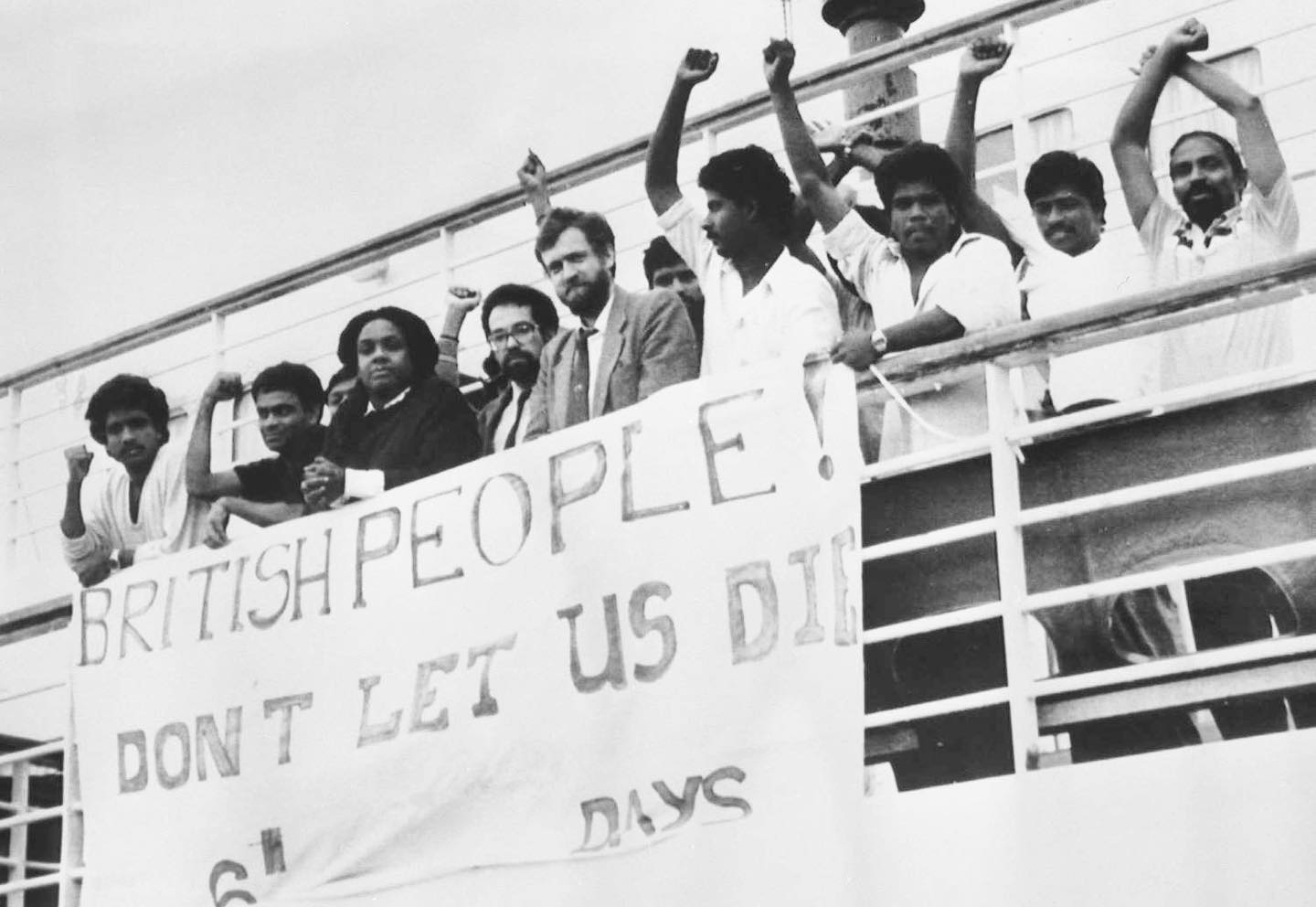

(Photo of British MPs Diane Abbott, Harry Cohen and Jeremy Corbyn alongside Tamil protesters on the Earl William)

(Photo Credit: Tamils for Corbyn)

On 15 October of 1987, the UK, France, and the Channel Islands were hit by the Great Storm of 1987. Roads and railways were strewn with fallen trees; rooftops and windows were shattered; and Britain’s national grid was so devastated that many areas were left without electricity. However, perhaps most importantly, the storm enabled over thirty refugees to escape detention of the ship, "Earl William".

Those who escaped were able to avoid being recaptured, forcing then Home Secretary, Douglas Hurd, to grant them "temporary admission". However, the refugees who were still on board were deported, subjected to further torture, and after a protracted legal battle, won asylum in the UK two years later.

It was in the summer of 1987 that Thatcher's government had decided to repurpose the recently privatised car ferry, the "Earl William", to use as a prison to detain refugees. The ship held 120 vulnerable people from countries such as Ethiopia, Iraq, Iran, Somalia, but the majority (60 people) were Eelam Tamil refugees. Conditions on the ships were criticised as a “prison-ship”, plagued with issues of overcrowding and of a lack of provisions, including sanitary towels. Detainees were locked out of their cabins between 7 am and 8 pm with restricted access to open-air decks due to concerns over suicide. Sadly, some onboard did take their lives whilst others staged hunger strikes protesting their detention.

Britain’s first Black woman MP, the then-newly elected Diane Abbott, attended protests on the ship alongside Labour MPs Jeremy Corbyn and Harry Cohen. Banners were displayed to the British public reading; “British people! Don’t let us die!” Recounting her visit, Abbott told the Mirror;

“I remember the visit to the prison ship vividly […] The young Tamils were completely desperate. It seemed a barbaric situation and I felt very sad for them. Conditions were poor and overcrowded.”

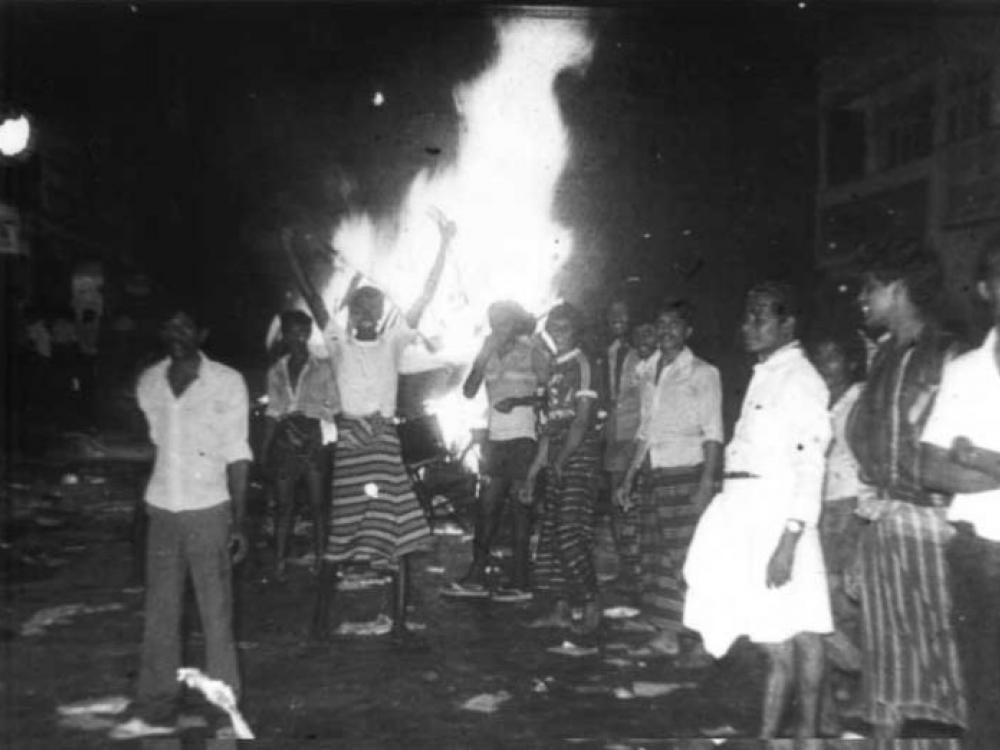

Sinhala rioters celebrate as they pause in the destruction of homes and businesses in Tamil sectors of Colombo

Tamil refugees were fleeing from an onslaught of racist violence in Sri Lanka. In July 1983, Sinhalese mobs, aided by state forces, burned Tamil homes and businesses to the ground, killing approximately 3,000 Tamil civilians. Two years later, Britain decided to lay visa restrictions on migrants coming from Sri Lanka. In that same year, Margret Thatcher, then British Prime Minister, travelled to Sri Lanka where she called for a “firm response” to “terrorists”.

In May, Thatcher was challenged by Corbyn during a House of Commons debate on the role of British Mercenaries in Sri Lanka.

" The Government were quite prepared for the oppression by the army in Jaffna, and the killing of so many people, to continue”.

According to a report in The Observer on 4 April, a special task force of police commandos at the disposal of the Sri Lankan Government have been trained by ex-SAS people from this country. The United Kingdom continues to give aid. The Prime Minister attended the opening of the Victoria dam and pledged further aid for the country. There is a military training arrangement and British Government support for police training in this country."

Despite the support of a handful of Labour MPs, Eelam Tamils found themselves with an increasingly hostile public. Interviewing members of the public, journalists detailed how British teenagers didn’t want “pakis” in their town; with one sailor proposing that ‘they should ferry them out into the Channel and kick them off into the sea’. In November 1986, this rhetoric evolved into violence. A firebomb was sent through a letterbox on Burgess Road, in the UK, killing three Tamil refugees.

“Flames haunted the Tamil people wherever they went”, wrote investigative journalist Phil Miller.

‘We will not be silenced’ – Tamil resistance

Tamil resistance to Thatcher’s administration took on multiple forms. Those first detained aboard the Earl William in early May 1987 were part of a group of 64 Tamils, including 24 women and 9 children, that the administration had failed to deport en mass earlier that year.

This was because of their successful "trousers down" protest in February during which Tamils stripped off on the Heathrow runway as they were being forced to board a plane back to Sri Lanka.

Sri Lanka’s High Commission attacked the credibility of Tamil asylum seekers claiming that they were there simply for “financial gain”, stating:

“They are coming here more than anything else for financial gain. If they are allowed to stay they are given all the social security benefits, they can send their children to school and will be housed free."

Only a handful of MPs were willing to defend the Tamil community. On 6 March 1987, Corbyn did just this;

"The Minister and the newspapers have sought to build up a case against Tamil asylum seekers, who have been accused, first, of being bogus refugees on the ground that they are not fleeing from personal danger, and secondly, of coming here through immigration rackets and for economic benefits [...]

Early this morning, I received a phone call from Sri Lanka from someone working on a fish farm there. He described graphically and with considerable emotion an incident that happened in Sri Lanka not long ago when there was a dispute some miles from his farm between the members of an army patrol and someone else. The army patrol headed straight for the farm, took out 26 farm employees and shot them, in the same way as thousands of other people have been shot in Sri Lanka [...]

The Government claim that the Tamils are not genuine asylum seekers, but there is a great deal of evidence that people deported to Sri Lanka by the Government have faced persecution, either from the armed forces or from Sri Lankan gangs".

Despite the protest of members of the Tamil community and a few MPs, the British establishment was willing to turn a blind eye to the plight of the Tamils.

Miller writes that a month prior to Black July, Whitehall gave two senior Sri Lankan police officers a VIP tour of the UK during which they were sent on an MI5 counter-terrorism course, and invited to visit the Metropolitan Police Special Branch to discuss ‘the activities of organisations based in the UK agitating for a Separate State for Tamils in Sri Lanka’.

Despite obstacles and surveillance that Tamils faced they refused to stay silent. A year after Black July, the Sri Lankan cricket team was invited to play their first test match at Lord’s. In response, Tamil activists stormed the fields.

Reflecting on the protests, one of the demonstrators told 47 Roots in July of this year:

“Looking back, I have no regrets. I did it for my people and my nation and I’m proud of that. We could not be censored. We could not be silenced. But sadly, thirty-six years later the situation back home still hasn’t changed and that's what hurts the most.”

After Earl William

The October storm of 1987 forced the Conservatives into a U-turn as they provisionally admitted those who had escaped, however, journalist Felix Bazalgette, notes that this amnesty was soon ended as the Home Office continued to quietly pursue many of the people it had released.

Bazalgette further reports the case of an 18-year-old Tamil refugee, held on the Earl William then deported along with four other Tamils back to Sri Lanka. Soon after his return he was imprisoned and beaten, accused of partaking in ‘subversive activities’ by local police. Bazalgette notes that evidence of “maltreatment only came to light after a dogged human rights lawyer, David Burgess, travelled to Sri Lanka to collect evidence pro bono, in order to hold the Home Office to account for failing to abide by the Geneva Convention”.

Burgess was successful in his case and the five Tamils were granted sanctuary. Sadly this was not a one-off incident. During and since the end of the armed conflict, Tamils have been continuously deported despite clear evidence that they were vulnerable to torture, rape, abductions, and extrajudicial killings in Sri Lanka.

At the start of this month, The Times reported that the UK was reconsidering process asylum applicants on disused ferries once more. These proposals were coupled with inquiries as to whether it was feasible to send refugees to overseas territories such as the Ascension Islands.

Commenting on these policy proposals, Siva, a Tamil refugee detained on the Earl William, stated:

“When I see desperate refugees swimming in the water from places like Syria where there is a civil war, I just feel so sad and angry […] My mind goes back to the time when I had to take a similar risk. The Government’s plans will create a terrible prison where people are sent to die. Their minds will be completely gone. It is a totally inhumane idea.”