Dozens of Sri Lankan protestors gathered outside the Indian High Commission in Colombo on Thursday, as controversy erupted over a renewable energy project that was handed to the Adani Group last year.

“Stop Adani, Stop Adani!” chanted the protestors in Colombo, as they held placards denouncing the Indian multinational conglomerate. “Hands off Sri Lanka,” rang another slogan.

.jpg)

The demonstrators, many of whom were also part of the ongoing anti-government protests in the Sri Lankan capital, had been fired up by recent remarks from the chairman of Sri Lanka’s Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB) as he spoke out on the Adani deal.

MMC Ferdinando told a parliamentary panel last week that the deal was only handed to the Adani Group due to the influence of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. In a video that has now been widely circulated, Ferdinando says he was summoned by Sri Lanka’s president Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who said “Modi is pressuring him to hand over the project to the Adani group”.

“He insisted that I look into it,” continued Ferdinando. “I then sent a letter that the President has instructed me and that the Finance Secretary should do the needful.”

"BJP’s cronyism has now crossed Palk Strait and moved into Sri Lanka," tweeted Congress leader Rahul Gandhi in the fallout from Ferdinando's comments.

.jpg)

(Photographs @EmDeeS11)

Rajapaksa immediately spoke out against Ferdinando’s statement, tweeting “I categorically deny authorisation to award this project to any specific person or entity.”

Just three days after his remarks, which sparked discontent across the island, Ferdinando resigned, claiming that he had “lied” during his testimony after being overcome with “emotion”.

Adani in Colombo

The Adani Group – headed by chairman Gautam Adani – has long been controversial. The company’s proximity to Indian prime minister Narendra Modi and its energy projects have stirred protests not just across India, but Australia too.

However, the now disputed renewable energy project in the Tamil North-East, is not the company’s first venture on the island.

Last year Adani Ports inked a deal worth a reported US$700 million to build a new container terminal in Colombo’s port.

The deal was controversial for several reasons. It came at a particularly difficult time for Indo-Lanka relations. The Sri Lankan cabinet had just decided to award a deal to a state-owned Chinese company for the second phase of the East Container Terminal (ECT) – a project that Delhi has been keen on for several years. The development of the port was initially agreed upon in May 2019 by the previous Sri Lankan regime, when former prime minister Ranil Wickremesinghe signed a memorandum of cooperation (MoC) with India and Japan to upgrade the terminal. The deal would have allowed the Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA) to retain full ownership, whilst India and Japan had a 49% stake in running the terminal. Over 70% of the transhipment business at the ECT comes from India.

In 2021, and under a new Rajapaksa-led regime however, Sri Lanka unilaterally abandoned the deal, reportedly worth an estimated US$500 - 700 million.

The withdrawal of the ECT deal set off a cascade of concerns from New Delhi, with one diplomat claiming it would “naturally have a rupturing effect on bilateral relations”.

In an apparent attempt to placate some of the consternation from India, Sri Lanka instead offered up the West Container Terminal (WCT). Adani inked the deal, which gave it a 51 per cent stake in the terminal partnership, while John Keells will hold 34 per cent and the Sri Lanka Ports Authority 15 per cent.

Yet, it still remains unclear how the Adani Group was chosen for the project. Whilst Sri Lanka claims that the firm was put forward by India, New Delhi insists that was not the case. Indeed, the Indian High Commission released a statement claiming that any nomination of the Adani Group and approval of the WCT deal was “factually incorrect”.

An air force helicopter to Mannar

.png)

Weeks after the deal was signed Gautam Adani visited Sri Lanka where he met with Gotabaya Rajapaksa and his powerful older brother Mahinda Rajapaksa. From Colombo, the billionaire businessman went on to visit Mannar – the proposed site of the renewable energy project – on a Sri Lankan air force helicopter.

Adani in an airforce helicopter landing in Mannar, 2021.

"The Adani group has yesterday explored the possibility of investing in Sri Lanka’s wind and renewable energy sector," Nalinda Ilangakoon, the Vice Chairman of CEB, said at the time.

In December, the group submitted a proposal to the Board of Investments of Sri Lanka (BOI) and the Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB) to develop a USD $1 billion renewable wind power project in Mannar. The proposal would see the development of a 1,000 MW wind energy project in Mannar and has also expressed interest in a second wind energy project in Poonakary - both situated in the Tamil homeland.

The China factor

China’s Ambassador Qi Zhenhong at the Nallur Kandaswamy Temple in Jaffna, 2021.

The announcement of the project was accompanied by other reports of resurging Indian involvement in the North-East, an area that New Delhi has sought to build ties with for decades.

Relations between New Delhi and Colombo had grown fraught, on the back of Sri Lanka cancelling several previously agreed deals. But as Sri Lanka’s economic crisis began to worsen, India swiftly stepped in.

As the USD $1 billion renewable wind power project in Mannar from Adani was announced, a Chinese project to develop three hybrid power plants in Delft Island, Analativu and Nainativu, worth an estimated USD$12 million was cancelled.

“We originally intended to carry out this project under a loan from an international financial institution, and a Chinese firm was selected through the standard bidding process,” said Sri Lankan State Minister Duminda Dissanayake. “But the Indian Government has offered a 75% grant for this purpose, and, therefore, we have cancelled the contract for the time being.”

The Beijing-based Global Times cited “security concerns from a third party” as the alleged reason behind the contract cancellation.

“It is ridiculous that India uses security reasons to meddle in the project,” a source close to the company told the Global Times. “The Sri Lankan project is small, supplying electricity to villages on three small islands. Since the islands and the main territory of Sri Lanka are separated by the sea, it is very likely that the power grid will not be connected to other places in Sri Lanka.”

Shrugging off the snub, however, China moved the power plant project to the Maldives. India meanwhile, continued to expand its footprint in the North-East.

Basil Rajapaksa meets India's Union Minister for Housing & Urban Affairs & Minister for Petroleum and Natural Gas, Hardeep Singh Puri in 2021.

In December, then finance minister and yet another Rajapaksa sibling Basil Rajapaksa visited New Delhi, where an agreement to develop the Trincomalee Tank Farm was signed – a reversal from a previous Sri Lankan position.

Earlier this year, the Indian government revived talks with Sri Lanka on linking the two countries’ electricity grids, a project that it has sought to carry out for several years, according to a report in Reuters. “The project envisioned a transmission line that would run from Madurai in Tamil Nadu to Anduradhapura in north-central province of Sri Lanka,” reported The Week.

In March 2022, Adani bagged the two renewable energy projects at a cost of US$500 million.

And though the deal had already been inked, last week Sri Lanka amended its electricity laws to eliminate competitive bidding for energy projects – a move that the energy minister Kanchana Wijesekara claimed was “essential to the quick development” of renewable energy.

Sri Lanka’s Indo-phobia

Protestors holding placards during a demonstration against CEPA in 2010 (File Photo)

As protestors gathered outside the Indian High Commission on Thursday, many slammed the lack of transparency around the deal. “Adani pollutes for profits,” read one placard. “No to Gota-Modi-Adani corrupt deals,” read another.

Though corruption and Adani’s climate record were the main drivers of the demonstration, the opposition to Indian involvement on the island follows a long record of hostility towards New Delhi reflected deeper rooted ‘Indo-phobic’ sentiments that have attempted to block Indian commercial access to the island.

For example, in recent decades successive Sri Lankan governments have resisted Indian attempts to finalise the Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA), a deal that would open up possibilities for greater trade and investment between the two countries. Bilateral discussions on CEPA stalled after protests by Sinhalese professionals and business groups opposing the agreement as a threat to Sri Lankan ‘sovereignty’. Protestors held placards denouncing CEPA as threatening “2,500 years of Sri Lankan Independence”.

"We heard that there is a lot of pressure from India over this project,” Shyamal Sumanarathna, secretary of the Ports, Commerce Industries and Progressive Workers Union told the Nikkei Asian Review last year over the now cancelled ECT deal. “But we are not a province of India, we are a sovereign nation and we do not need to dance to their tunes.”

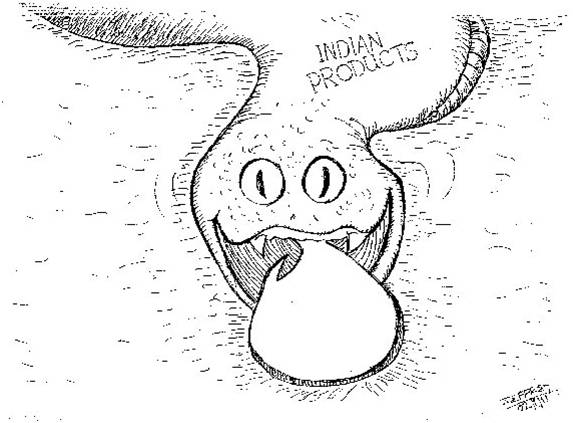

Cartoon published in The Island in 2010

As Tamil Guardian editor Thusiyan Nandakumar wrote in The Wire, “there is a chauvinistic logic to this Indian aversion”.

“Tamil Nadu, a powerhouse state with a population of almost 70 million, is a stone’s throw from the island’s Tamil North-East, and has a millennia-long history of close cultural and linguistic links,” he said. “Tighter trading ties to India could help revive the war-torn region and has repeatedly been called for by the island’s Tamils.”

Indeed, even as protests took place in Colombo, in Mannar – where the project is set to be constructed – there were no demonstrations against the deal.

The current protestors however, insist that their opposition to the project is different. “The bond between India and Sri Lanka is between [people],” declared a placard. “Not politico.”

.jpg)

We need your support

Sri Lanka is one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a journalist. Tamil journalists are particularly at threat, with at least 41 media workers known to have been killed by the Sri Lankan state or its paramilitaries during and after the armed conflict.

Despite the risks, our team on the ground remain committed to providing detailed and accurate reporting of developments in the Tamil homeland, across the island and around the world, as well as providing expert analysis and insight from the Tamil point of view

We need your support in keeping our journalism going. Support our work today.

For more ways to donate visit https://donate.tamilguardian.com.