Speaking at Stanford University’s Centre for South Asia, Senior Lecturer of Political Economy at the University of Jaffna, Ahilan Kadirgamar, and Tamil Guardian editorial board member, Viruben Nandakumar, discuss Sri Lanka’s current economic crisis; the expansion of the military establishment; and the island’s international relations.

A return to the 70s?

Kicking off the event Kadirgamar highlighted the parallels of the current crisis to the economic downturn of the 1970s, noting the 1973 OPEC oil crisis and the landslide victory of the right-wing United National Party (UNP).

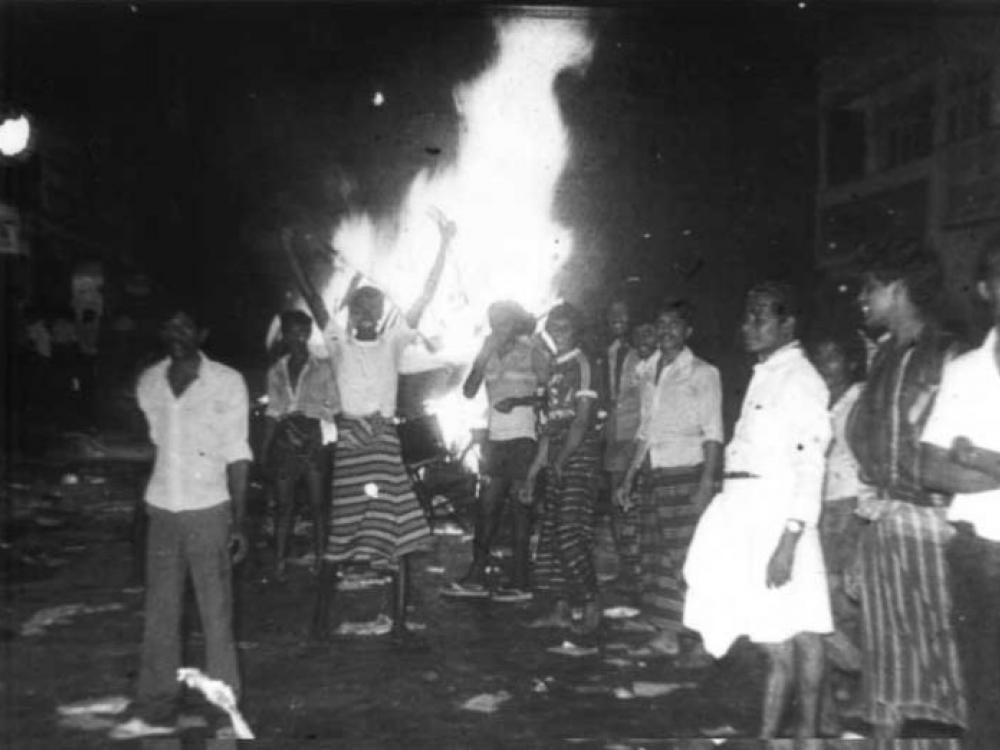

The ascent of J.R Jayewardene to the presidency marked a period of liberalisation as. He revealed his grand ambitions to build Sri Lanka as an “open economy”. The policies implemented by the Sri Lankan government enabled for trade liberalisation, the privatisation of local industries and for the inflow of capital from the West. It was further accompanied by the slashing of social spending through cuts to rice and food subsidies and infamously the crushing of the labour movement following the July 1980 strike. This enabled for a bubble of economic development however as wealth petered out this would lead the infamous 1983 anti-Tamil pogroms, Black July.

Kadirgamar attributes the genocidal violence of the pogroms to the neoliberal policies adopted by the UNP government and highlights the state’s complicity in the massacres. He further highlights that following the brutal atrocities of 2009, that concluded the armed conflict, Sri Lanka saw a “second wave of liberalisation” as Western finance flooded into Sri Lanka and the Rajapaksa administration pivoted once again to financialisation and urbanisation. Throughout this history, Sri Lanka would continue to take on debt which would lead to the balance of payments issues that precipitated Sri Lanka’s current crisis.

Commenting on the budget announcement, Kadirgamar notes that Sri Lanka’s President Ranil Wickremesinghe refers back to the 70s and argues that “there was not enough liberalisation”.

A militarised model of development

![]()

Responding to a question on the development of Sri Lanka’s militarised form of governance and the impact on minority communities, Nandakumar responded by interrogating the term “minority”.

“Tamils do not identify under the label of minority. They see themselves as a nation, a people unified by collective and common history, culture and language”.

This, Nandakumar notes, contrasts with the project of Sinhala Buddhist nationalism which sees Sri Lanka as a unitary state and try to preserve its Sinhala Buddhist structures.

“This is rooted in not only almost exclusively Sinhala military or in Sri Lanka’s constitution, which explicitly maintains the state’s responsibility to preserve Buddhism, but increasingly in the landscape of the North-East as Buddhist viharas are erected against the will of the non-Buddhist local population”.

Reflecting on the Jayewardene administration, Nandakumar notes that the military takes on two roles:

“The first being to crush ideological and national opposition to the Sinhala state; and the second being a means of shoring up support for his administration by alleviating poverty in the predominately rural Sinhala south […] By the 1990s, the military had become the largest state employer”.

Despite the lack of credible threats, “the role of the military has not been rolled backed” Nandakuumar states. “Instead, it has been expanded further. Today, Sri Lanka’s military is twice that of the UK’s despite being a third of the population. The country is spending more on the military than health and education combined and this is following a deadly pandemic and a devastating economic crisis”.

“The military is also running a litany of activities from hotels, airports, seaports, fisheries, land development, and even the pandemic response. This is hardest felt in the North-East where the military is increasing land grabs, growing agriculture on this stolen land, then selling the produce back to the inhabitants and below market rates to cut out competitors. This is further impoverishing communities across the North-East”.

Nandakumar highlights that “there is no mention of the need to roll back the military” in Wickremesinghe’s budget announcements despite the UN finding a worrying trend of militarisation and a deep culture of impunity which were key factors behind Sri Lanka’s current economic malaise.

Sri Lanka’s debt crisis

Asked on the role of China and India in Sri Lanka’s current crisis, Kadirgamar noted the often the geopolitical struggles are overemphasised the ground economic reality.

Reflecting on Sri Lanka’s debt he noted that 35% of external debt is through sovereign bonds, which held an exorbitant interest rate and have produce little in return. This is in contrast to bilateral debt which stands only at 10% or debt to China which similarly stands close to 10%. “Chinese debt was not the cause but sovereign bonds” Kadirgamar maintains.

Sri Lanka increasingly lent on sovereign bonds in the aftermath of the armed conflict as the island moved towards increasing financialisation. This model of economic development, Kadirgamar stresses, is unsustainable and inextricably led to Sri Lanka’s economic crisis.

Commenting on geopolitical shifts he notes whilst tensions between India, China and the US are unfolding on the island; the chief interest of these powers is in strategic assets such as ports.

Military aid

Commenting on the role of international and military aid to Sri Lanka, Nandakumar highlighted how successive Sri Lankan administrations were bankrolled by the international community which supported its military endeavours. This was even as Sri Lanka would engage in a genocidal assault on the North-East which included the indiscriminate shelling of hospitals, food-lines and “no-fire zones”, where civilians had been encouraged to gather.

Despite these atrocities, and even the protest of the senior US politicians, the IMF and World Bank were content with the mass casualties under the belief that this would lead to prosperity. Whilst the stock market in Colombo quadrupled in the 18 months after the war, Nandakumar notes that this wealth was fleeting as, “it did not resolve the underlying issue of Sinhala Buddhist nationalism”.

Commenting on Sri Lanka’s “strategic ambiguity”, Nandakumar highlights how India and the US have soft-pedalled the issue of human rights with Sri Lanka given its strategic significance in the Inso-Pacific region and concerns over China’s growing influence. He notes however that Sinhala nationalism has driven the island into opposition with India over growing concern over its exertion of influence on the Tamil national question. Instead, China became the preferred partner under the Rajapaksa given is unflinching defence of Sri Lanka during its genocidal warfare.

Despite a brief spat between Sri Lanka and China, caused by Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s poorly thought out ban on chemical fertilisers, Sri Lanka has continued a favourable policy towards China allowing for the docking of Yuan Wang 5, despite Indian protest. China’s ambassador has also met with Mahinda Rajapaksa showcasing their belief in the political stock of the Rajapaksa family.

Addressing the economic crisis

Responding to a question on the economic direction Sri Lanka should take, Kardigarmar reflected on Wickremesinghe’s budget announcement and stressed that it seemed oblivious to economic and food crisis Sri Lanka citizens were suffering from.

“The average day wage labour’s salary has contracted 50% but food prices have increased 90%” Kardigarmar noted. He added that the island’s economy itself is predicted to shrink by 10% this year.

“If we don’t have the right kinds of policies we will see the economy contract again next year” he warned.

Kardigarmar emphasised the need to increase agriculture production and address the food crisis, however, he also highlighted Sri Lanka’s crisis of democracy. He stated that the current government lacks legitimacy.

Whilst doing so he claimed that “Sri Lanka has been overdetermined by the ethnic conflict” and put faith in the aragalaya asserting that its focus on class issues had galvanised all people in Sri Lanka.

Expect further repression

Commenting on the proposed rehabilitation bill, Nandakumar noted that the bill “is the latest in a long line of draconian legislation that enables the security forces sweeping powers. The legislation enables for the compulsory detention in centres of “drug dependant persons, ex-combatants, members of violent extremist groups and any other group of persons.” It has further drawn comparison to the Chinese draconian treatment of Uighurs in the Xinjiang province. Whilst Sri Lanka’s Supreme Court has decried the bill as unconstitutional it may still pass with amended language.

The proposal comes amidst growing demands for Sri Lanka to repeal its current counter-terrorism legislation, the Prevention of Terrorism Act 1979, which garnered widespread international condemnation for similarly allowing for arbitrary arrests and forced confessions. The legislation introduced under Jayawardene was intended as a temporary act but has since been used as a means of targeting Tamil and Muslim youth for as grave a crime as writing poetry or attending a political rally. It has been linked to cases of enforced disappearance, torture and sexual violence. Whilst Sri Lanka has repeatedly pledged to repeal the legislation it has failed to do so.

The European Union is set to release a report reviewing Sri Lanka’s progress under the GSP+ arrangement which enables for favourable trade concessions.

We need your support

Sri Lanka is one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a journalist. Tamil journalists are particularly at threat, with at least 41 media workers known to have been killed by the Sri Lankan state or its paramilitaries during and after the armed conflict.

Despite the risks, our team on the ground remain committed to providing detailed and accurate reporting of developments in the Tamil homeland, across the island and around the world, as well as providing expert analysis and insight from the Tamil point of view

We need your support in keeping our journalism going. Support our work today.

For more ways to donate visit https://donate.tamilguardian.com.