This week, Instagram disabled the Tamil Guardian accoount, without any notification or prior warning. However, this is not the first time that the website has been the target of attempts at censorship. In December 2020, Twitter notified the editors of the Tamil Guardian that Sri Lanka’s Criminal Investigations Department had formally written to the social media platform, calling for posts by the news website to be removed.

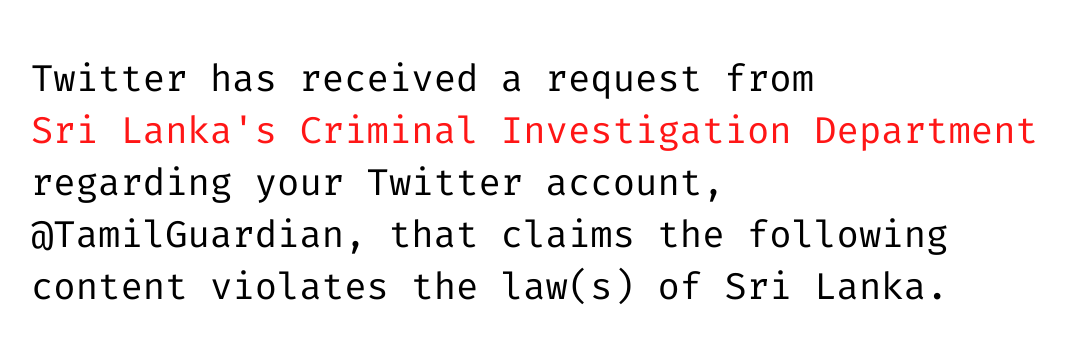

“In the interest of transparency, we are writing to inform you that Twitter has received a request from Sri Lanka's Criminal Investigation Department,” reads an email from Twitter sent on Monday, December 7th 2020.

It went on to note that the Sri Lankan authorities claimed that content posted by the Tamil Guardian “violates the law(s) of Sri Lanka” and flagged two tweets in particular.

The first was a series of photographs of a projection on to Britain's Houses of Parliament in Westminster, Central London, that took place on November 2020. The projection of a karthigaipoo flower and the words “we remember” was organised by British Tamil activists, to commemorate those who lost thir lives in the Tamil liberation struggle amidst restrictions in the UK due to the coronavirus pandemic.

More photographs from London where earlier tonight a Karthigaipoo, the national flower of Tamil Eelam, was projected on to Britain's Houses of Parliament to mark Maaveerar Naal.

https://t.co/atfXyXysRe #MaaveerarNaal #tamil #eelam #britain #uk #Parliament #lka pic.twitter.com/GCISg9h6zj— Tamil Guardian (@TamilGuardian) November 27, 2020

The second tweet was a story on how Tamil political leaders and celebrities in Tamil Nadu had marked the 66th birthday of the LTTE leader Velupillai Prabhakaran's with events and posts on social media.

Tributes from Tamil Nadu for Prabhakaran’s 66th birthday https://t.co/4qSjGMenG4 #tamil #eelam #ltte #HBDதேசியத்தலைவர்66 #HBDLeaderPrabhakaran66 #HBDTamilsLeaderPrabhakaran pic.twitter.com/WouF0dr5Le

— Tamil Guardian (@TamilGuardian) November 27, 2020

“We have not taken any action on the reported content at this time as a result of this request,” said Twitter in its email to the Tamil Guardian, adding that “as Twitter strongly believes in defending and respecting the voice of our users, it is our policy to notify our users if we receive a legal request from an authorized entity (such as law enforcement or a government agency) to remove content from their account”.

.png)

Full text of the email sent to the Tamil Guardian.

Repression ramping up

“When we received the request, we were initially just shocked,” said Ben Andak, an editor at the Tamil Guardian. “Our first thoughts were with our correspondents on the ground.”

The Tamil Guardian has a team of correspondents based across the North-East who contribute stories to the website, often facing great risk in doing so. Journalism remains a dangerous occupation on the island, particularly so for Tamils, many of whom have been murdered or disappeared in the line of their work.

Examining data from, Journalists for Democracy (JDS) in 2013, Together Against Genocide (TAG) found that of all the reported murdered or disappeared journalists listed by JDS since 2004, 37 are media workers of ethnic Tamil origin while 4 are ethnic Sinhalese and 2 Sri Lankan Muslims. The advocacy group went on to observe that approximately 75 per cent have taken place in the majority Tamil-speaking regions of the island.

“Our team has frequently faced harassment from the Sri Lankan security forces and this notification came at a time when that repression was ramping up” continued Andak. "Being a journalist in Sri Lanka is dangerous. Being a Tamil journalist is deadly."

The attempt by Sri Lanka’s CID to censor the Tamil Guardian came just over a year after former defence secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa returned to power as Sri Lanka’s president. With his previous tenure having seen the murder of dozens of media workers, this regime has begun cracking down on dissenters and jailing journalists, poets and even those who have shared posts on social media.

Military overwatch

Rajapaksa’s renewed crackdown has been overseen by the ever-growing Sri Lankan security forces. Chief amongst them is the Sri Lankan army, headed by Shavendra Silva – a credibly accused war criminal who is barred from travel to the United States for his role in executing surrendering Tamils in 2009.

In 2019, the head of Sri Lanka’s army Shavendra Silva labelled “threats” from social media posed “serious concerns for national security”. The general went on to compare “misguided youths sitting in front of the social media” to suicide bombers, just weeks before Rajapaksa would take office and a renewed crackdown on freedom of expression was to begin.

.jpg)

Sri Lankan soldiers part of the cyber security force last year.

The focus on the internet from the Sri Lankan armed forces is not new. In 2011, the former commander of the Sri Lankan army Jagath Jayasuriya warned troops to “be prepared for the cyber war after the physical war”. In 2017, an entire army unit focussing on ‘cyber security’ - the 12th Signal Regiment - was inaugurated.

Since then, arrests and detentions have been frequent.Recent months alone have seen civilians and journalists who have shared posts on social media, including Facebook, arrested by the Sri Lankan security forces under terrorism charges.

Requests to Twitter

Though Sri Lanka has resorted to more violent methods to silence jouranlists in the past, this is the first time that a fomal request to Twitter from the security forces has been made public.

Twitter says that it keeps a log of removal requests that it receives from governmental entities and lawyers representing individuals to “remove or withhold content”..jpeg) In the case of Sri Lanka, the request to remove Tamil Guardian’s content is one of strikingly few. Twitter says it received only 4 legal demands from January 2012 until December 2020, with 12 different accounts reportedly named.

In the case of Sri Lanka, the request to remove Tamil Guardian’s content is one of strikingly few. Twitter says it received only 4 legal demands from January 2012 until December 2020, with 12 different accounts reportedly named.

Though Twitter did not comply with the requests from Sri Lankan authorities, that has not always been the case with other governments. Earlier this year, under pressure from the Indian government, the company said it permanently blocked over 500 accounts, as Delhi looked to stifle dissent from activists and journalists across the country.

“Though our tweets were not removed in this instance, the requests set a dangerous precedent,” said Andak. “It showed the Sri Lankan state was actively targeting the social media accounts of Tamils on the island and around the world.”

It was not just on Twitter that this was happening.

This week, Instagram disabled the Tamil Guardian account, without any prior warning. It followed several years of both Instagram and Facebook censoring posts on their platforms.

“News articles covering events on the island, historical photographs documenting Sri Lanka’s ethnic conflict and even political artwork have all faced removal,” said a Tamil Guardian statement on Wednesday. “Other Tamil nationalist content and accounts have also faced similar hurdles.”

“The Sri Lankan state has one of the most authoritarian and repressive approaches to stamping out freedom of the press,” said Tamil Guardian editor Sharmini Vara. “Tamil social media accounts are now well and truly in their scope. Though our Twitter account remains active, our Instagram and Facebook accounts have both faced censorship. It is up to these big tech platforms to review their policies and make major decisions.”

“Do they want to side with those who uphold freedom of expression and share the principles of a free and fair press? Or are they going to continue to pander to authoritarians and those who have violently silenced the media? Big tech must do better.”

We need your support

Sri Lanka is one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a journalist. Tamil journalists are particularly at threat, with at least 41 media workers known to have been killed by the Sri Lankan state or its paramilitaries during and after the armed conflict.

Despite the risks, our team on the ground remain committed to providing detailed and accurate reporting of developments in the Tamil homeland, across the island and around the world, as well as providing expert analysis and insight from the Tamil point of view

We need your support in keeping our journalism going. Support our work today.

For more ways to donate visit https://donate.tamilguardian.com.