This year marks 36 years since the Black July pogroms. The brutal state-sponsored violence by Sinhala mobs lasted a week and saw the death of at least 3,000 Tamils, destruction of 5,000 shops, and displacement of over 150,000 Tamils. At least 500 Tamil women were raped and many families were burned alive. It also prompted the first large exodus of Tamils: 500,000 fled the island, giving seed to a global Tamil diaspora.

The Black July pogrom carried all the hallmarks of genocide: most notably, mobs were armed with voter registration lists distinguishing Tamils as targets of violence. In this nightmarish rampage against the Tamil people, it is unsurprising that the motivations behind such horror have been reduced into a cause-and-effect narrative. Many of us are familiar with this version: the LTTE killed 13 Sri Lankan soldiers, the next day Sinhala mobs ran amok, supposedly in an outburst of rage in response to the Sinhala deaths. The underserved truth, however, is that the pogrom began before the Tigers’ attack reached public consciousness.

The events preceding the pogroms make it abundantly clear that Black July was not a spontaneous spur of violence against Tamils — it was premeditated. It was a genocide rooted in increasingly hostile and violent conditions restricting Tamil life and survival. The following is an account of the months leading to Black July and the state’s deliberate commission or permissiveness of anti-Tamil violence on the island. It is important to note these accounts are not an exhaustive list of events but an attempt to illustrate the pervasiveness of steadily increasing state violence against Tamils.

April 1983

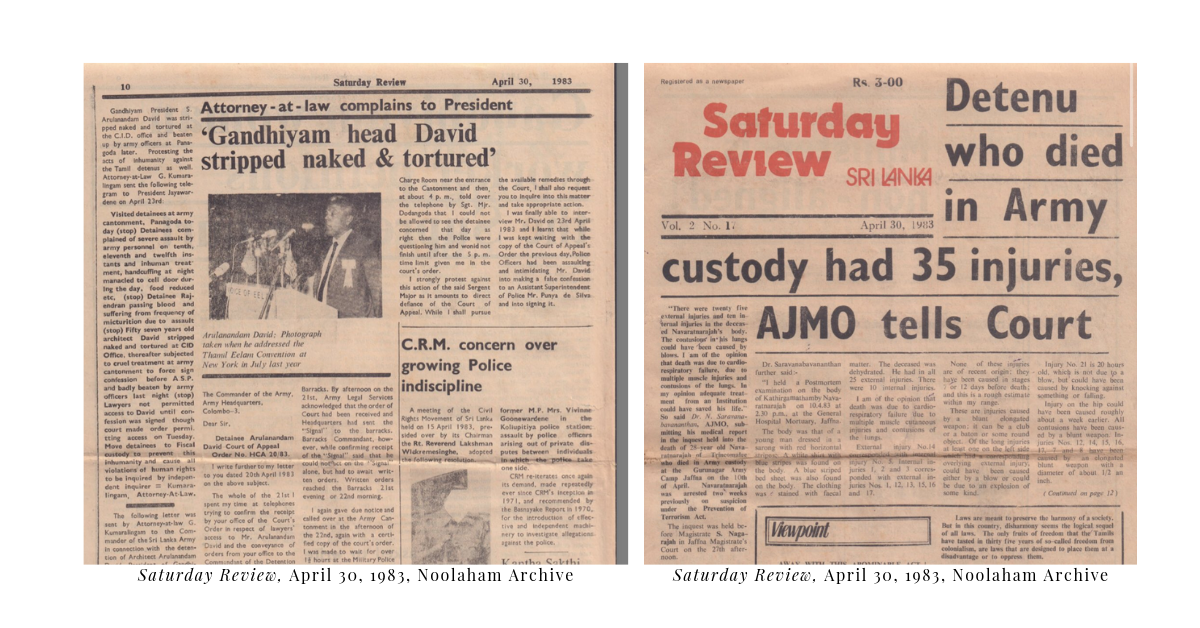

The government began wielding the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) (1979) to arbitrarily arrest and detain Tamil civilians. Notably, founding members of the Gandhiyam Movement, Arulanandam David and Dr. S. Rajasundaram, were arrested and severely tortured for months. Dr. Rajasundaram was eventually killed in the government-sanctioned Welikada Prison Massacre during Black July.

Later, an inquest into the April 10 custodial death of another Tamil detained under the PTA, Kathirgamathamby Navaratnarajah, at the Gurunagar army camp, near Jaffna, found evidence of him to have suffered 35 injuries. The police attempted to steal the evidence files underscoring their guilt. Yet another inquest found Ratnasingam Sriskandarajah of Karainagar was murdered in army custody after his detention under the PTA as well.

May 1983

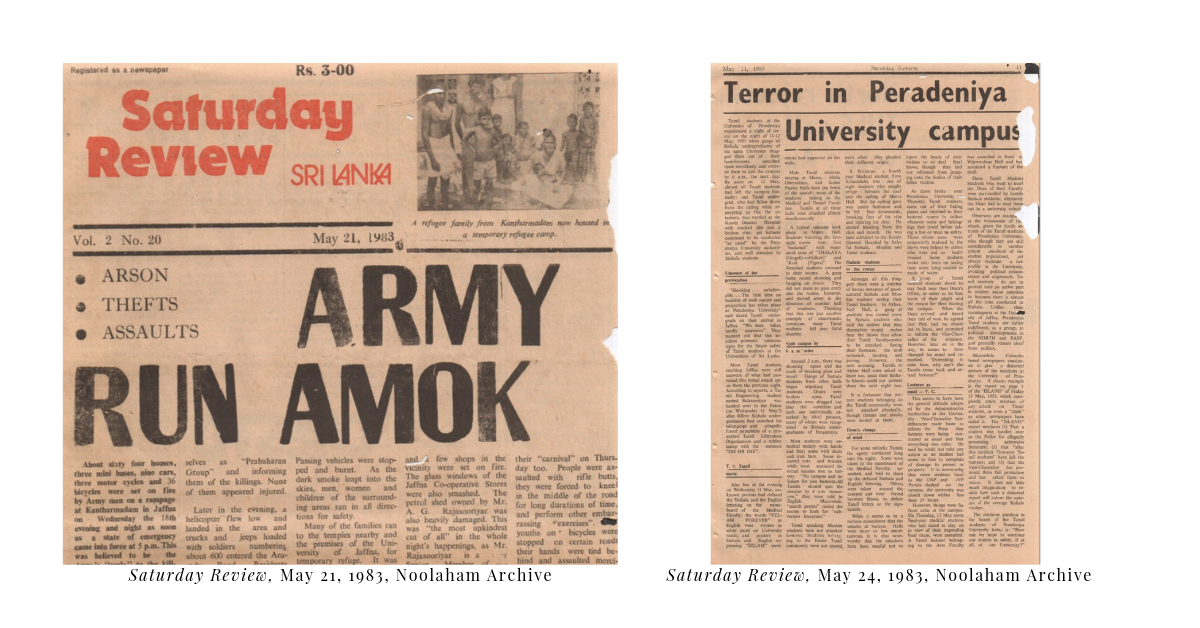

Following a call for a boycott of the May 18 local elections by the LTTE, a shootout killed one army corporal. Later that day, a helicopter bearing about 600 soldiers landed in Jaffna and set the town aflame. Houses, shops, and public institutions were reduced to ashes while being looted and robbed by the army.

In Colombo, Tamil students at educational institutions were facing increasing discrimination, harassment, and violence. At Peradeniya University, mobs of Sinhala students are reported to have broken into the rooms of Tamil students and assaulted them with iron clubs and bars. Despite complaints to the administration, they took no meaningful action to address Tamil students’ concerns and many abandoned their studies out of fear for their safety.

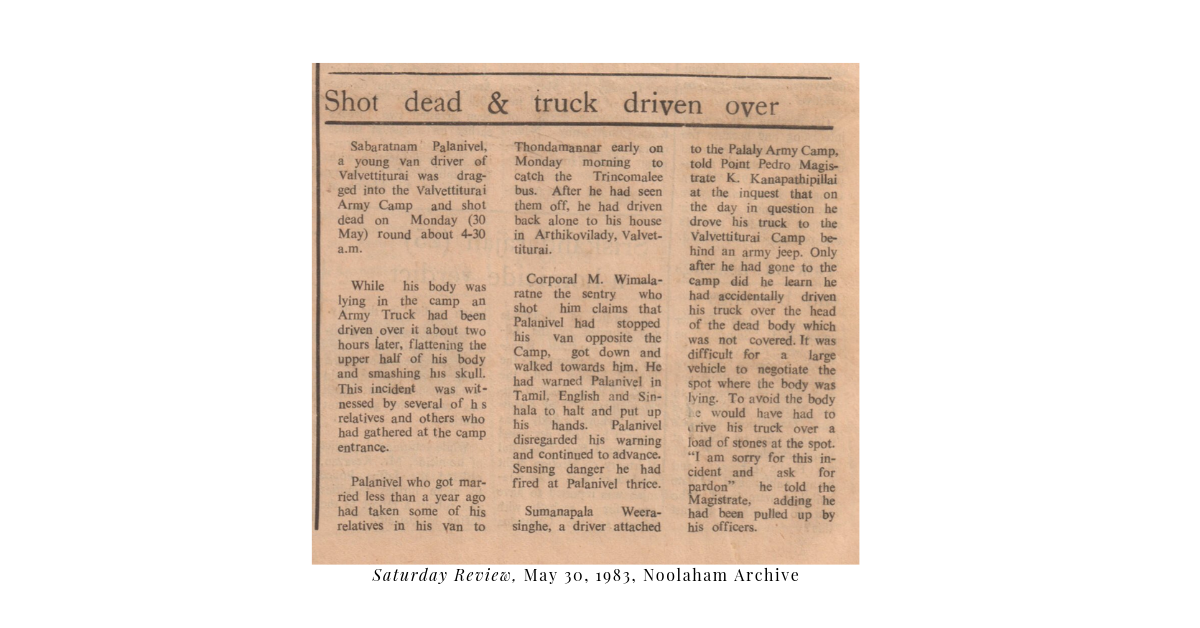

In another instance of anti-Tamil violence, Sabaratnam Palanivel of Valvettithurai was dragged into the town’s army camp after driving his family to the train station. Army personnel repeatedly shot him before driving over and flattening his body with an army truck. His relatives watched in horror.

June 1983

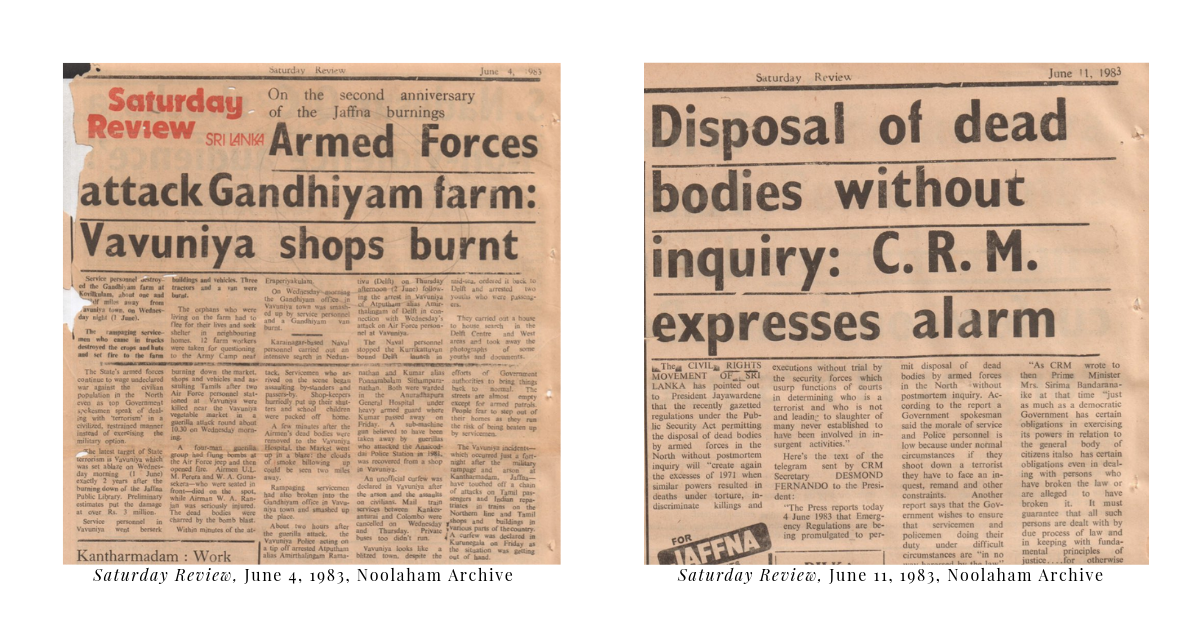

On June 1, a Tamil armed group killed two Sri Lankan Air Force men in an ambush in Vavuniya. Following the attack, military personnel indiscriminately burned buildings and attacked Tamil bystanders. Soldiers also attacked Gandhiyam offices and farms, jolting residing orphans to run and hide. This pogrom prompted a string of attacks on Tamil train passengers on the Northern line and Tamil-owned shops across the island.

The government outright sanctioned military violence against Tamils by enacting Emergency Regulation 15A, permitting the armed forces to dispose of dead bodies without a judicial inquest or even a post-mortem. A telegram by Civil Rights Movement Secretary Desmond Fernando to President J.R. Jayewardene stated: “The morale of servicemen and police personnel is low because under normal circumstances if they shoot down a terrorist they have to face an inquest, remand, and other constraints.” The regulations came into effect soon after judicial inquiries findings that the army killed Tamil detainees in Jaffna and Karainagar, as detailed above.

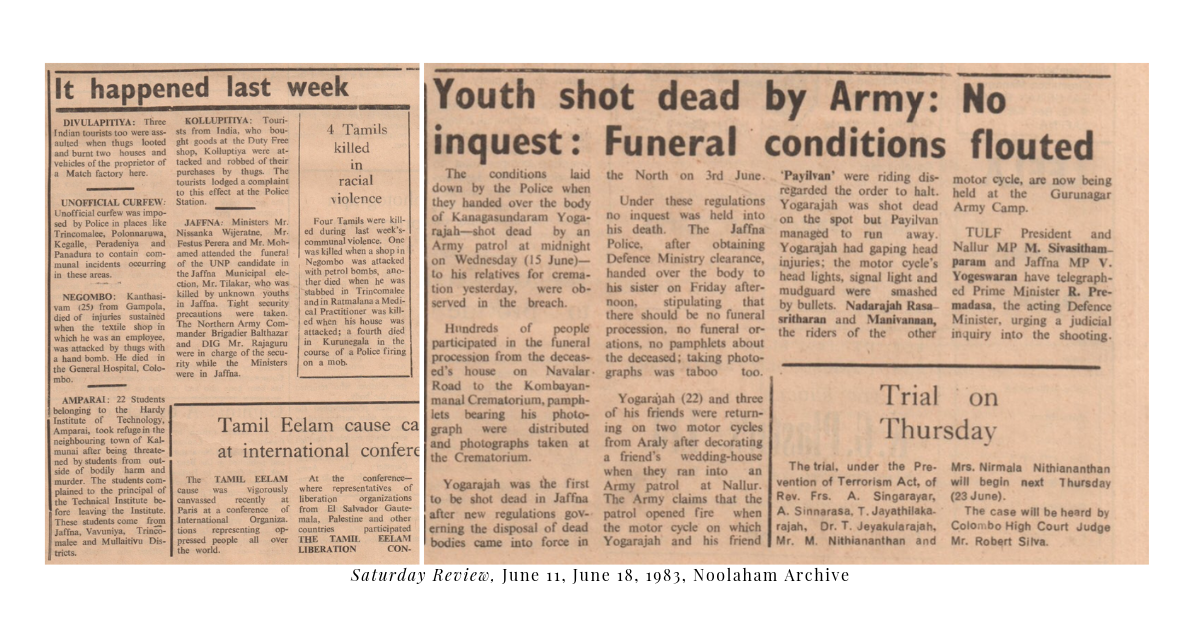

Throughout June, anti-Tamil violence only increased across the island. Tamil homes and businesses were set ablaze by Sinhala mobs, killing dozens of Tamils. In Jaffna, the army killed several Tamil youths and refused to hand over their bodies. Under the new regulation, no inquests were held.

In their June issue, the London-based Tamil Times reported that “Not a single day has passed since 18th of May without attacks upon Tamils in some part or other of the country.”

July 1983

On July 1, the government banned the publication of the Saturday Review and Suthanthiran, the two main papers reporting and printing in Jaffna. Due to strict censorship, information beyond this point went unreported or was only reported by diaspora media.

Throughout July, violence against Tamils grew. The army abducted and raped three Tamil girls in Jaffna in custody; news spread that one had killed herself.

On July 23, the LTTE conducted the deadliest attack on the Sri Lankan military by the Tamil liberation struggle till date, killing 13 Sri Lankan soldiers in an ambush in Thinnevely. Soon after, state-sponsored violence against Tamils reached a climax in the genocide known today as Black July.

Government-sponsored Sinhala mobs were equipped with voter registrations lists to specifically attack Tamil people across the island. Often untold is the dispersal of the pogroms. They did not occur in Colombo alone, and although the exact names of all the towns and villages affected remain unknown, the seven-day pogrom spanned the island.

.jpg)

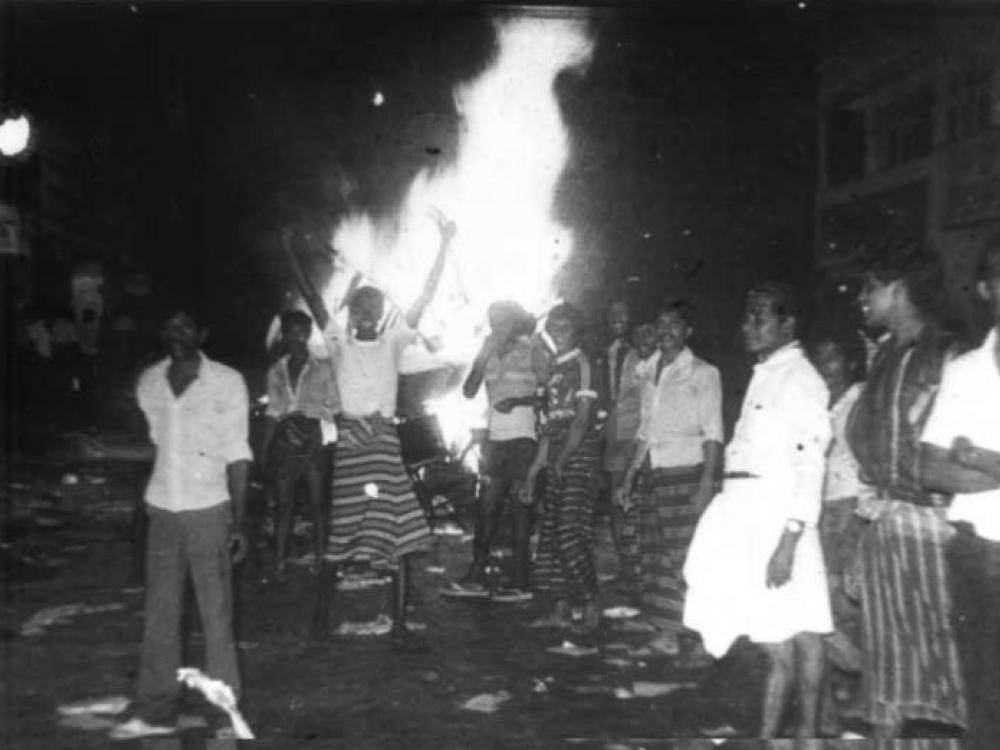

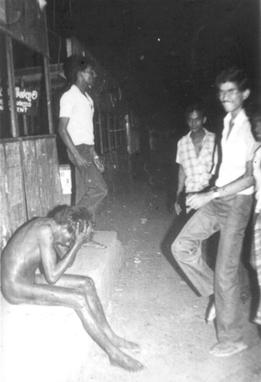

Black July’s cruel violence remains seared into the collective memory of Tamil survivors. Vans bearing escaping Tamil families were set alight. Angry mobs poured kerosene on Tamil homes, businesses, and bodies with triumphant joy while state security forces stood silent. There is even evidence of Tamil children being thrown into burning cauldrons of tar. In one of the most haunting photographs depicting the violence, a Tamil man is stripped naked, arms covering the sides of his face in an attempt to shield the blows; a Sinhalese man confronts the camera mid-kick with a smirk.

While many had been accustomed to racist attacks, the size and severity of the Black July genocide jolted the Tamil nation. Black July signalled a point-of-no-return for Tamils, invigorating the Tamil armed struggle and initiated a 26 year-long war. The government, instead of holding itself and other perpetrators accountable, responded by outlawing Tamil demands for self-rule and a separate state. On July 30, the London Times wrote: “When presented with evidence that the army had committed atrocities against the Tamils, the government has reacted with a shrug of the shoulders”.

The legacy of the pogroms followed a severe degree of intentional state-inflicted violence on the Tamil people. The structural discrimination, violence, and impunity that enabled unquestioned disposal of Tamil bodies only worsened, fostering widespread support to a militant movement. A fight for a separate state of Tamil Eelam. This fight persisted for nearly three decades before tragically ending in 2009 with another state-sponsored genocide against the Tamil people.

In uncovering our history, we possess the ability to safeguard our truths and more intimately understand our struggle. This would not be possible without the meticulous archival work by Noolaham.net and Sangam.org, for which we are incredibly grateful.

PEARL’s petition to the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights seeking formal recognition of the Tamil genocide and criminal justice for atrocity crimes against the Tamil people during the war’s final phase is still open — please sign and share widely.

We need your support

Sri Lanka is one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a journalist. Tamil journalists are particularly at threat, with at least 41 media workers known to have been killed by the Sri Lankan state or its paramilitaries during and after the armed conflict.

Despite the risks, our team on the ground remain committed to providing detailed and accurate reporting of developments in the Tamil homeland, across the island and around the world, as well as providing expert analysis and insight from the Tamil point of view

We need your support in keeping our journalism going. Support our work today.

For more ways to donate visit https://donate.tamilguardian.com.