Artwork courtesy of Shaumya Sankar (@_shaumy)

For months relatives of the forcibly disappeared have been protesting on the streets across the North-East, demanding to know the whereabouts of their loved ones. Despite years, sometimes decades, of various government mechanisms and pledges, their search for answers continues.

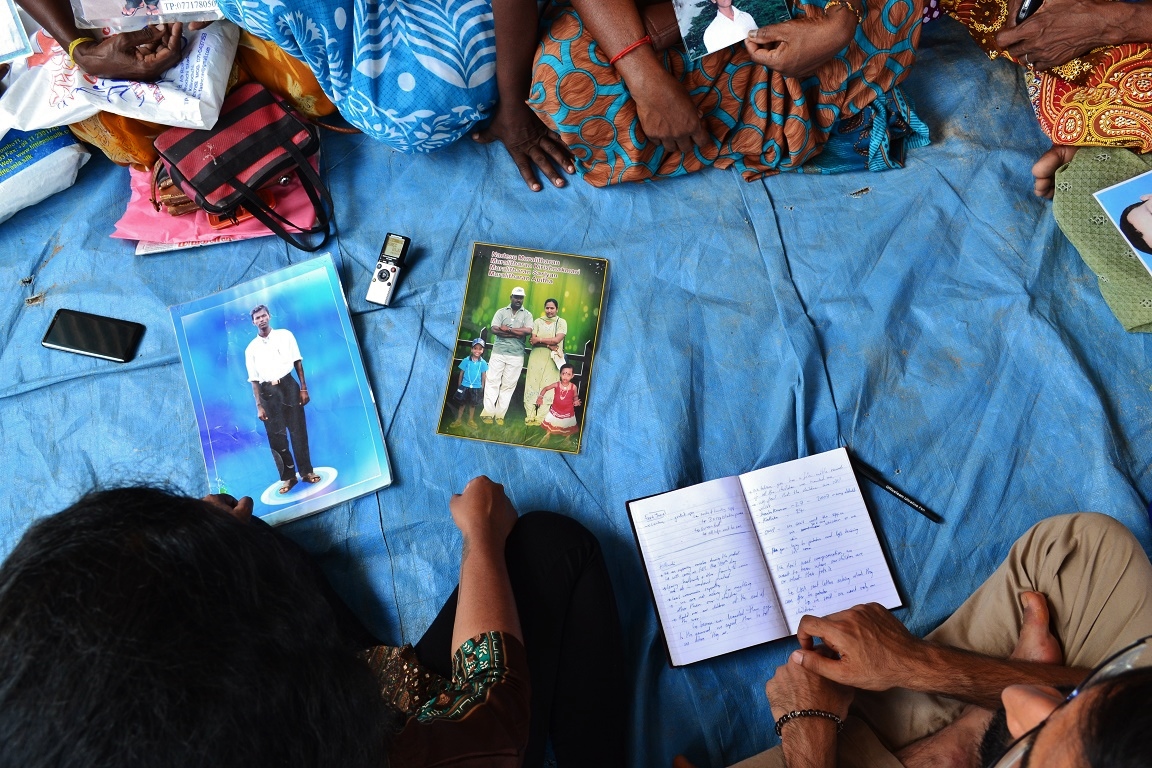

In this series of interviews conducted since May 2017, Tamil Guardian goes behind the protest to the individual stories that make up this unyielding movement of Tamil families of the disappeared.

Her daughter Kirishnakumari, son-in-law Nadesu and their two young children Sarujan and Abitha were all last seen on the 18th of May 2009. Nadesu, a member of the LTTE, had surrendered alongside hundreds of others members and their families to the Sri Lankan military. The whole family, including 5-year-old Sarujan and 2-year-old Abitha, were forced on board a Sri Lankan military bus.

They were with Father Francis Joseph, says Ponamma, a priest who was negotiating the surrender. “Whether they stayed for one day or many or even one minute, if you are with the LTTE, you surrender,” she recalls the Sri Lankan military telling them. “Whilst we were afraid to surrender Father Joseph came and convinced us not to worry. He promised on his life that if we surrender, we will be forgiven.”

“I too went to get onto the bus,” she adds. “My husband and youngest daughter went along with our bag.” But the Sri Lankan military stopped then. Since that day, no-one who boarded - neither Father Joseph nor the two children or their parents - have been seen since. “We trusted our children with them and handed them over… Still to this day I do not know where my children are,” says Ponamma. “We gave our children away with our own hands”

Ponamma is one of hundreds of mothers who have taken to the streets across the Tamil homeland, demanding the return of their loved ones. She, like the others with her, firmly believe that their relatives are alive and that the Sri Lankan military knows exactly what happened to them.

“They ought to tell us,” she says. “We handed our family over, it would be a different matter if they were taken or kidnapped because the government could not answer that, but we handed our children over.”

“Who is holding our children? Where are they? Why are they hiding the truth? These children are not just pen lids or 5 or 10 rupees to say that you have lost.... If our sheep or goat had gotten lost we would not sleep... but we handed over human beings.”

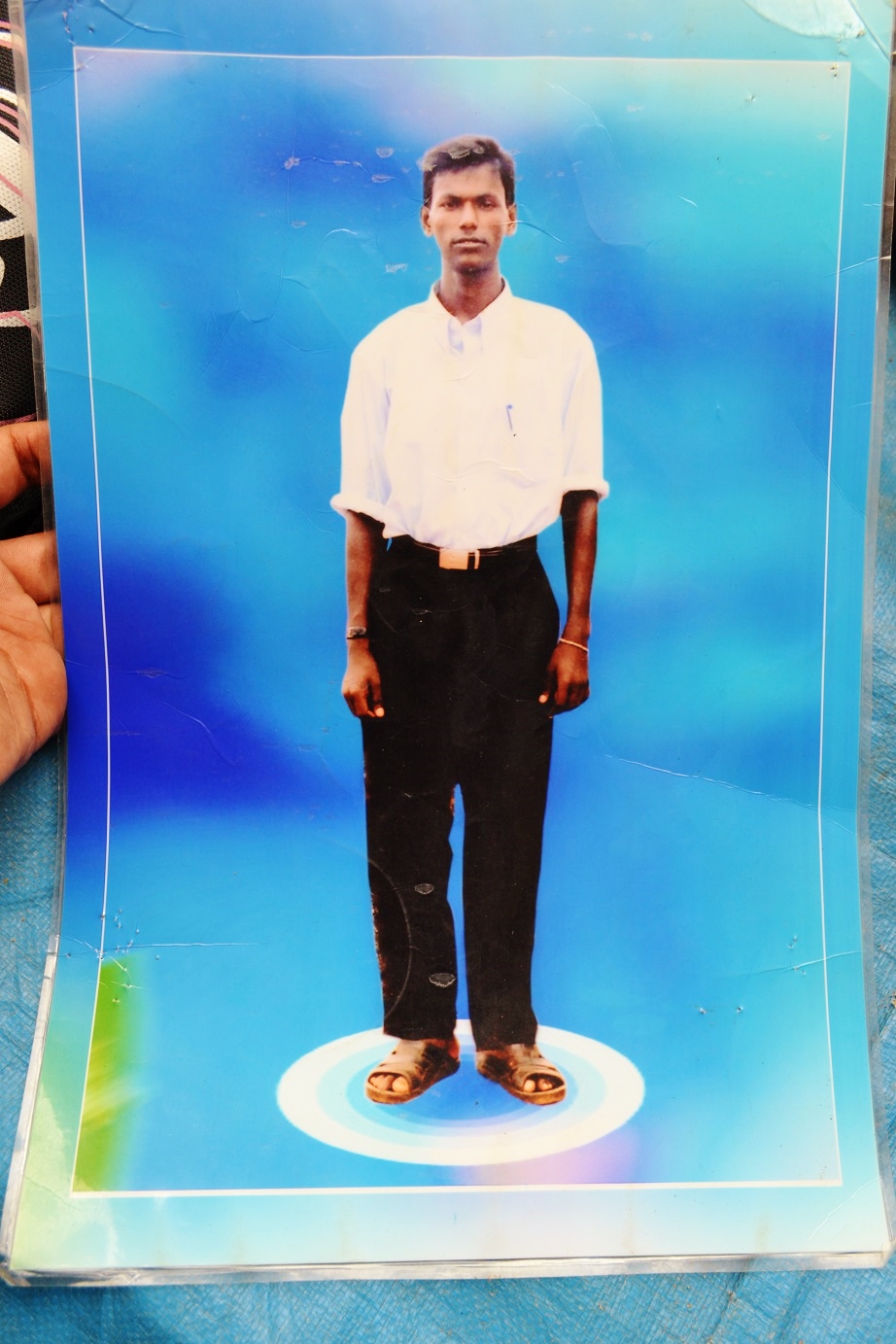

“What did that young child do?” she asks, gesturing towards a photograph of her grandchild.

In particular, Ponamma points to statements made by the Sri Lankan military, where they claimed to have kept a list of all Tamils who surrendered to the security forces during the final phase of the armed conflict. Though the mothers, alongside Tamil civil society, human rights groups and Tamil politicians have repeatedly called for such a list to be released, the military has remained steadfast in its refusal. Despite initially admitting that such a list had been kept, the military now denies its existence. “Do you know what he said?” asks Ponamma, referring to a military officer who initially told a Sri Lankan court a surrender list had been kept. “That he got stressed and that’s why he said it.”

This is not the only tragedy to have struck her family. In 2006, her son Ravichandran was also forcibly disappeared, last seen at the Omanthai military checkpoint, on the border of the then-Sri Lankan military controlled territory. The Centre for Human Rights and Development (CHRD) reports that the army acknowledged it had done a “customary search” of Ravichandran. It denies it has any knowledge of his whereabouts.

Ponamma filed complaints with the ICRC, Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka, and the police before filing petitions for habeas corpus in Sri Lankan courts, reports CHRD. The organisation adds,

“In each of these cases, the State’s Objections in the habeas corpus case fail to respond to allegations and evidence that the missing person was last seen in State custody.”

“They told us Mahinda was only the one who did this and a better government is emerging and we should vote for them,” she laments. “We believed them. We voted for them. And still have no answers.”

The mothers of the disappeared met with the Sri Lankan president last year, and handed him a list of demands. In particular the families called for a list of a received by the Sri Lankan military to be released – a demand recently put forward to the commissioner of the Office of Missing Persons by protesting families in Mullaitivu. The mothers are still waiting for the list to be produced.

“The Sri Lankan President celebrates the harvest joyfully, but only tears fall from our eyes,” she says. “Do they not think of us? He is married and has kids the same way we do.”

“We want the President to immediately give us answers and tell us where our children are… if this was any other ordinary citizen they would have been helped by now. For the President to inflict so much pain on us we deserve answers.”

“Just because we are Tamil does not mean you can torture us like this. Everyone is human.”

Foreign government and international NGOs too have come to visit the protest site in Kilinochchi, she notes, but still there has been no progress. “Someone will come and ask us why we are sat here, but they will not ask to speak to the government to find our children.” The international community, in particular, must act she says. “How many times have we been told to leave it in the government’s hand,” she asks.

“There are so many hardships,” she says. “There are too many old mothers who are yearning for their children… The government is punishing us for the children that we ourselves sent. I lived with my children, I do not have anybody else. Why are they doing this to us at this elderly age… look at how many days we have been out here.”

“We just want our children,” she says, in tears and completely exacerbated. “You kept us in barbed wire. You could’ve just bombed us and killed us then… I am a mother… how am I alive? I shouldn’t be able to walk on this planet… we should drink poison and die in front of them.”

“So many women leave their children at home and come here. There are so many difficulties of being away from home, but we do so because we believe we will get our children back.”

The pain of not knowing where her family are affects her every day, she adds, pointing to the collection of photographs of her grandchildren that she carries. Many are of her grandchildren playing with toys and with massive smiles on their faces. “This is the time where they should be coming to us, playing around and sitting in our laps. Instead, we are in pain, in tears, and holding their pictures.”

“I do not remember the last time I peacefully ate. How can we just sit at home knowing our children are out there somewhere?”

“All we want is our children back. That is all we ask.”

-----

On May 18th 2018 Ponamma was part of a group of mothers who spoke at an event in Jaffna on their ongoing struggle to find their disappeared loved ones.

“They are talking about this Office of MIssing Persons,” she said. “We don’t want that office. What is the use? How many thousands of photocopies have we made?... We are reduced to tears.”

“Why are you torturing Tamils so much?”

Extracts of her address are below. See more from the ITJP here.

We need your support

Sri Lanka is one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a journalist. Tamil journalists are particularly at threat, with at least 41 media workers known to have been killed by the Sri Lankan state or its paramilitaries during and after the armed conflict.

Despite the risks, our team on the ground remain committed to providing detailed and accurate reporting of developments in the Tamil homeland, across the island and around the world, as well as providing expert analysis and insight from the Tamil point of view

We need your support in keeping our journalism going. Support our work today.

For more ways to donate visit https://donate.tamilguardian.com.