| JR Jayewardene discussing the military assault on Jaffna with a commander. |

A set of recently declassified CIA reports reveal how Sri Lanka’s former president J R Jayewardene attempted to garner military support from the United States and position himself as a moderate dedicated to solving the island’s ethnic crisis, even as the Sri Lankan army was committing large scale human rights abuses in the North-East.

Declassified documents from the CIA show how despite regarding himself as “South Asia’s elder statesman and a political moderate” the Sri Lankan president “had twice ordered his forces to take Jaffna” as part of a massive military assault on the peninsula.

“Burn the place to the ground,” Mr Jayewardene admitted he had instructed his forces.

The military however, refused, he revealed in an hour-long meeting with Peter Galbraith, a staff member for the US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations in 1988. Facing stiff resistance from Tamil militants in the peninsula, military commanders went against the order “on grounds of unacceptably high casualties,” leading to the failure of Sri Lanka’s ‘Operation Liberation’.

|

|

| Sri Lankan troops prepare for the assault on Jaffna |

The documents provide a detailed insight from an American perspective into the tumultuous events of the time and shed light on their assessment of the Sri Lankan president.

Following the Black July riots of 1983, hundreds of thousands of Tamils had been displaced and the ethnic conflict on the island had intensified, with the Sri Lankan military on the offensive in the North-East. Mr Jayewardene, who undertook a more Western-centric free market approach to the island’s economy by devaluing the rupee, liberalising imports and reducing government subsidies, was keen to further garner US support. One document stated how for years the president had been “trying to embroil the United States in Sri Lanka’s affairs”. Even during the 1983 pogrom, he had “requested US security assistance, including weapons, small river craft and advisers” as well as suggesting “a friendship treaty” between the two countries.

|

| The Sri Lankan president gives a gift of an elephant to US president Ronald Reagan during his state visit to Washington. |

His invitation to meet then US President Ronald Reagan in Washington in 1984 was lauded by Sri Lanka’s state media. Senior US defence officials had already visited the island several times, but according to US Embassy reports, Mr Jayewardene saw his state visit “as an integral part in his general policy of rehabilitating Sri Lanka’s tarnished international image,” after reports of human rights abuses committed against Tamils had begun to regularly reach headlines across the world. “The island’s largely government-directed press has already begun to describe the Washington trip as an “honor” to the government and people of Sri Lanka, marking it a “turn around in the slide of our reputation as a country”,” said one recently declassified document.

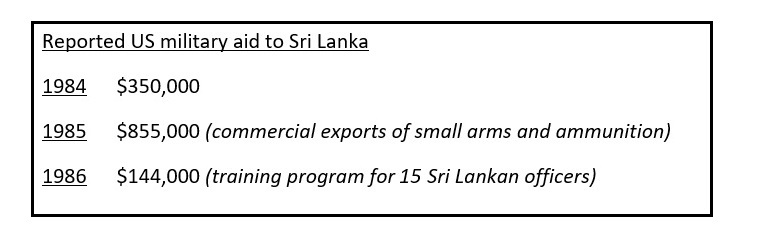

US military aid to Sri Lanka that year was $350,000 stated the reports and Mr Jayewardene was likely to use that trip to push for further military support, as he had done in a visit to Beijing earlier that year. Under his tenure, the United States had already expanded the ‘Voice of America’ relay station north of Colombo, but he was desperately searching for even closer co-operation. Previous requests for increased military support had been turned down noted one report, referring to a specific call from Sri Lanka for AH-1 Cobra helicopter gunships that had been rejected.

“We would like the people of America to understand us,” he said in a speech in Washington. “In the long history of Sri Lanka, there have been difficult periods. There have been murders; there have been assassinations; there have been riots; there have been good deeds and bad deeds”. Last July we had one of those bad periods,” he said, referring to the Black July riots which saw thousands of Tamils killed by government-backed mobs. “But in time to come, it will be forgotten.”

With the Cold War still raging, Mr Jayewardene sought to cast the ethnic problem on the island as one of a Marxist insurgency. “The terrorists are a small group who seek by force, including murder, robberies, and other misdeeds, to support the cause of separation, including the creation of a Marxist state in the whole of Sri Lanka and in India, beginning with Tamil Nadu in the south,” he declared. American intelligence agencies seem to have bought in to aspects of the argument, with one entire report on the impact of Marxism on the Tamil insurgency agreeing that the People’s Liberation Organisation of Tamil Eelam (PLOTE) posed the “most serious long term security threat to the government”, with their call for an “island-wide revolution in Sri Lanka as well as establish a Marxist Tamil state”.

Despite this, it seems US intelligence services urged caution when it came to publicly backing the Sri Lankan president. “Increased identification with Jayewardene at this time could damage US prestige in the region and in parts of the Third World,” said one assessment. “It could be perceived by other small ethnic groups as acceptance by the United States of the use of repression against minorities.”

A deeper analysis of the Sri Lankan president’s motives and actions was also conveyed in the dozens of released documents. Mr Jayewardene “portrays himself as a communal moderate, but in his long political career he has played both sides of the ethnic fence”, said another assessment, noting that his government had “implemented increasing repressive antiterrorism measures in the Tamil-dominated north”. Sri Lanka's Prevention of Terrorism Act, put in place by Mr Jayewardene in 1979, remains in place today. Current Sri Lankan Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe served as the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs at the time.

Indeed, Mr Jayewardene's visit to Washington was criticised by human rights groups with adverts slamming the Sri Lankan government appearing in Washington and New York newspapers. His comments to the London-based Daily Telegraph, where he infamously said that if he was to “starve the Tamils out, the Sinhala people will be happy”, had not been forgotten.

|

| Sri Lanka's Minister of National Security Athulathmudali meets with troops in the mid 1980s. |

Yet, commercial exports of small arms and ammunitions still flowed to Colombo, reaching a total of $855,000 in 1985, and US military assistance to Sri Lanka the following year including “a small training program for 15 Sri Lankan officers” with a $144,000 budget. Sri Lanka continued to push ahead with military spending, more than doubling the defence budget, expanding recruitment and reaching out to countries such as Israel, Pakistan and the United Kingdom, who through a private company trained Sri Lanka’s notorious Special Task Force (STF). With this massive expansion of the security forces, human rights abuses also increased. “Composed largely of young Sinhalese with hardline views,” Sri Lankan soldiers would “draw little distinction between insurgents and Tamil civilians, leading to attacks on civilians” said a CIA report. “US Embassy sources assert the STF is behind most of the violence against Tamil civilians in Eastern Province,” it continued. “These sources report a common STF tactic when fired upon while on patrol is to enter the nearest village and burn it to the ground.”

Yet, commercial exports of small arms and ammunitions still flowed to Colombo, reaching a total of $855,000 in 1985, and US military assistance to Sri Lanka the following year including “a small training program for 15 Sri Lankan officers” with a $144,000 budget. Sri Lanka continued to push ahead with military spending, more than doubling the defence budget, expanding recruitment and reaching out to countries such as Israel, Pakistan and the United Kingdom, who through a private company trained Sri Lanka’s notorious Special Task Force (STF). With this massive expansion of the security forces, human rights abuses also increased. “Composed largely of young Sinhalese with hardline views,” Sri Lankan soldiers would “draw little distinction between insurgents and Tamil civilians, leading to attacks on civilians” said a CIA report. “US Embassy sources assert the STF is behind most of the violence against Tamil civilians in Eastern Province,” it continued. “These sources report a common STF tactic when fired upon while on patrol is to enter the nearest village and burn it to the ground.”

|

| Victims of the 1985 Kumudini boat massacre, one of several such killings to take place across the North-East, as the Sri Lankan army ramped up operations. |

Sri Lanka’s intensified war efforts would make little headway militarily or politically concluded the Americans, stating despite the proliferation, the security forces were “incapable of waging a successful counterinsurgency campaign against Tamil separatists”.

Nevertheless, Sri Lanka pushed ahead with its intense military campaign and continued its economic blockade of Jaffna. As the humanitarian crisis in the peninsula worsened, India’s central government found itself under increasing pressure to intervene. Its initial attempt to send an aid flotilla with 40 tonnes of food and medical supplies to Jaffna was blocked by the Sri Lankan navy vessels, leading to the Indian Air Force air-dropping supplies over the town in Operation Poomalai in July 1987. The Sri Lankan president was incensed.

The issue of Indian involvement had already stirred up a Sinhala backlash from the south. Some years earlier, Mr Jayewardene had told a visiting US Senator that he found India’s role in the conflict to be “reprehensible”. “I have never seen J R as deeply emotional or agitated over what he considers to be an egregious assault by India in Sri Lanka’s internal affairs,” read a report of the 1984 meeting with US Senator Charles Percy.

Sri Lanka though faced a military stalemate. ''The military promised us that victory was always around the corner,'' a top aide to Mr Jayewardene was quoted as saying. ''They never delivered, and finally we stopped believing them.” With pressure from India mounting, the Sri Lankan president entered the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord in July 1987.

The Sri Lankan president “stressed, though with obvious bitterness, that none of his outside friends would help him,” read one document written after the deal was signed.

The accord, which paved the way for Indian troops to enter the island, was deeply unpopular in the Sinhala south, stoking fears of an Indian invasion of the island – a notion that persists today. The signing of the deal provoked such fierce protests and criticism that a Sri Lankan soldier attacked Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi with his rifle during a ceremonial guard of honour in a visit to Colombo later that year. For his part, Mr Jayewardene was accused of a “betrayal” of Sinhalese interests and a group called the Patriotic People's Movement labelled him a traitor. Weeks after the deal was signed the group claimed responsibility for an assassination attempt on the president, where hand grenades and bullets were fired at the Sri Lankan cabinet as it met in parliament.

Even through the massive Sinhala backlash, pressure from the Indian government forced Colombo into the accord - a move that the USA backed. The international community was geared into pressuring Colombo into accepting that there was no military solution for the conflict, and the Sri Lankan president found that American support in particular was lacking.

He ended up telling the Americans that he “had no choice but to make a deal”.

|

| The Sri Lankan president signs the Indo-Lanka Accord alongside Indian Prime Minsiter Rajiv Gandhi in July 1987 |

Read the reports at the CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room here.

We need your support

Sri Lanka is one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a journalist. Tamil journalists are particularly at threat, with at least 41 media workers known to have been killed by the Sri Lankan state or its paramilitaries during and after the armed conflict.

Despite the risks, our team on the ground remain committed to providing detailed and accurate reporting of developments in the Tamil homeland, across the island and around the world, as well as providing expert analysis and insight from the Tamil point of view

We need your support in keeping our journalism going. Support our work today.

For more ways to donate visit https://donate.tamilguardian.com.