On the morning of September 16th 2008, Benjamin Dix was part of a United Nations convoy that was driving out of Kilinochchi. A massive Sri Lankan military offensive was drawing closer and Tamils trapped in the region feared the destruction it would bring. International humanitarian agencies decided they could no longer stay in the Vanni. “Civilians were protesting outside our offices begging us not to leave,” he recalls. “As we drove out that morning a Kfir - a government fighter jet - flew over the top of us and into the Vanni… It almost haunts me”.

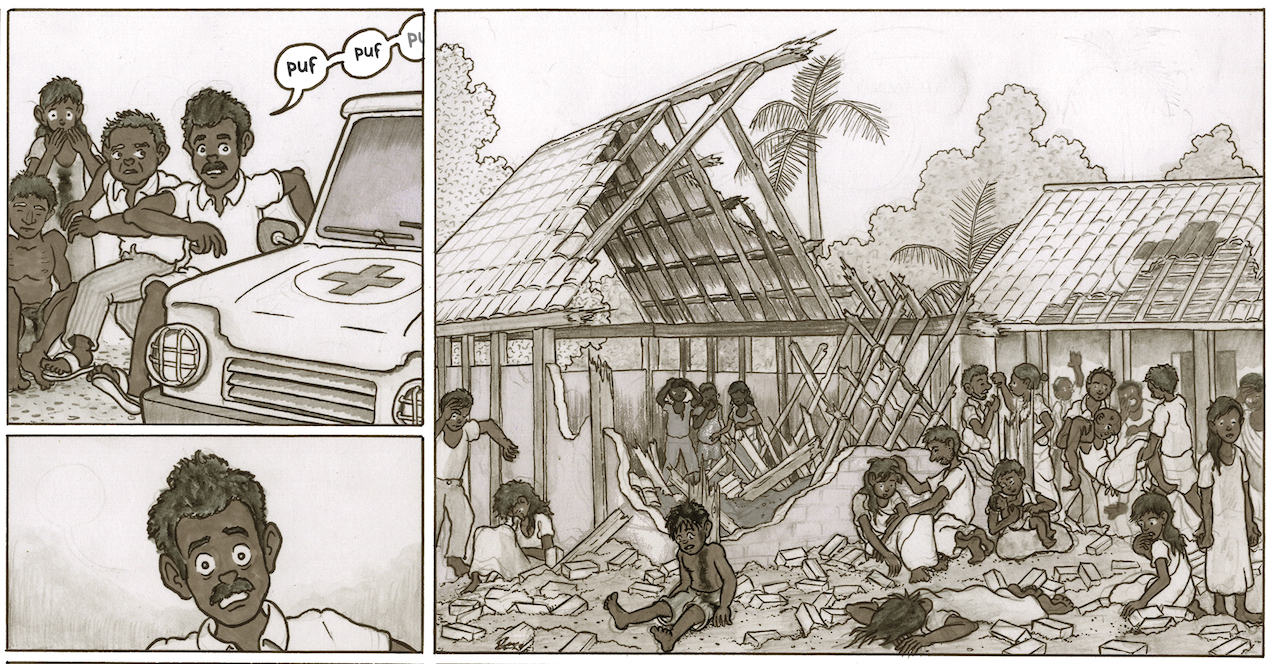

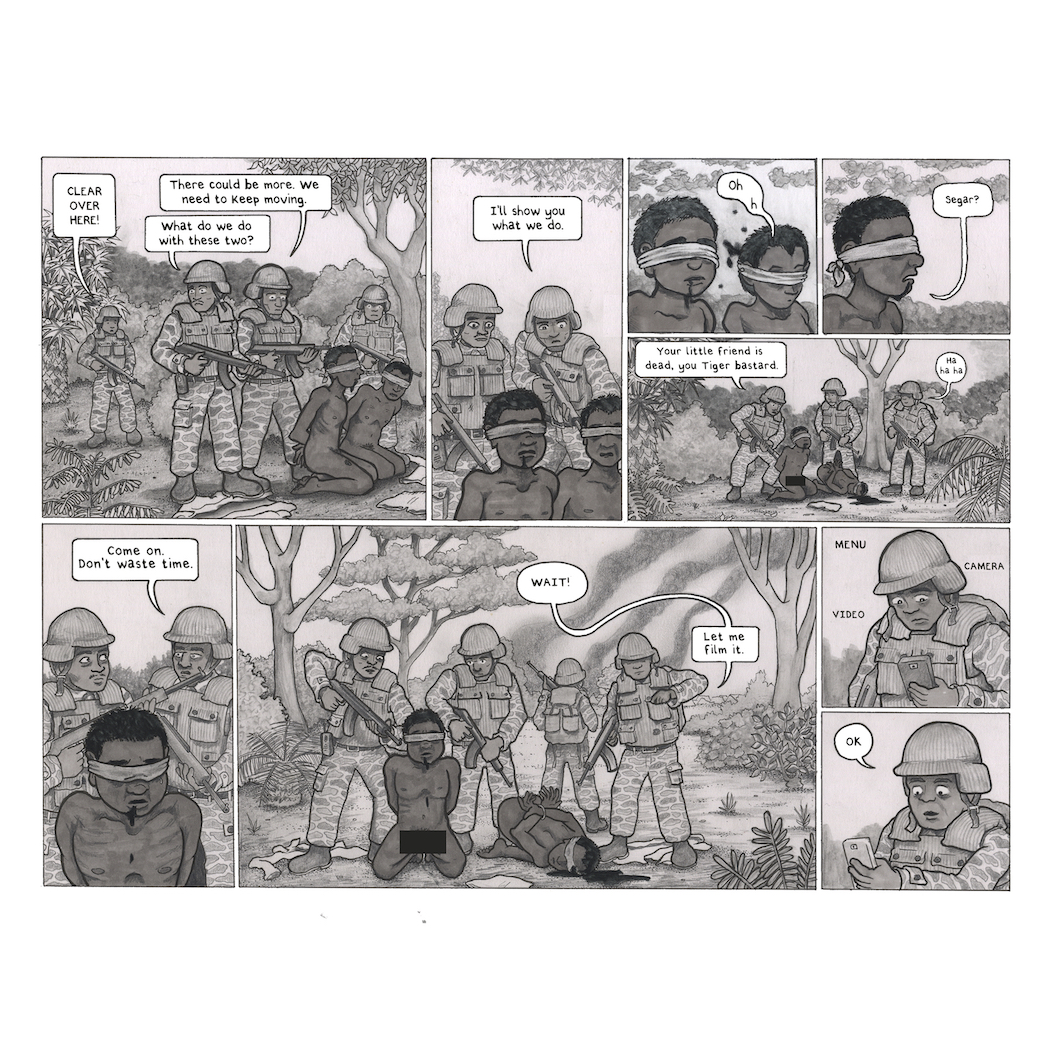

After a further eight brutal months of heavy weapon bombardment, the Sri Lankan government declared victory over the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. There were reports of violations of international humanitarian law, including the shelling of hospitals, the executing of surrendering Tamils and widespread sexual violence. Tens of thousands of Tamil civilians had been killed. “That sense of failure in the international community,” Dix continues.”That’s something I’ll never come to terms with.”

A little over a decade later he still has not fully processed all the events of that time. “I came out of Sri Lanka with a ball of negative traumatic energy in my soul,” he tells the Tamil Guardian in London last week. “A broken heart.”

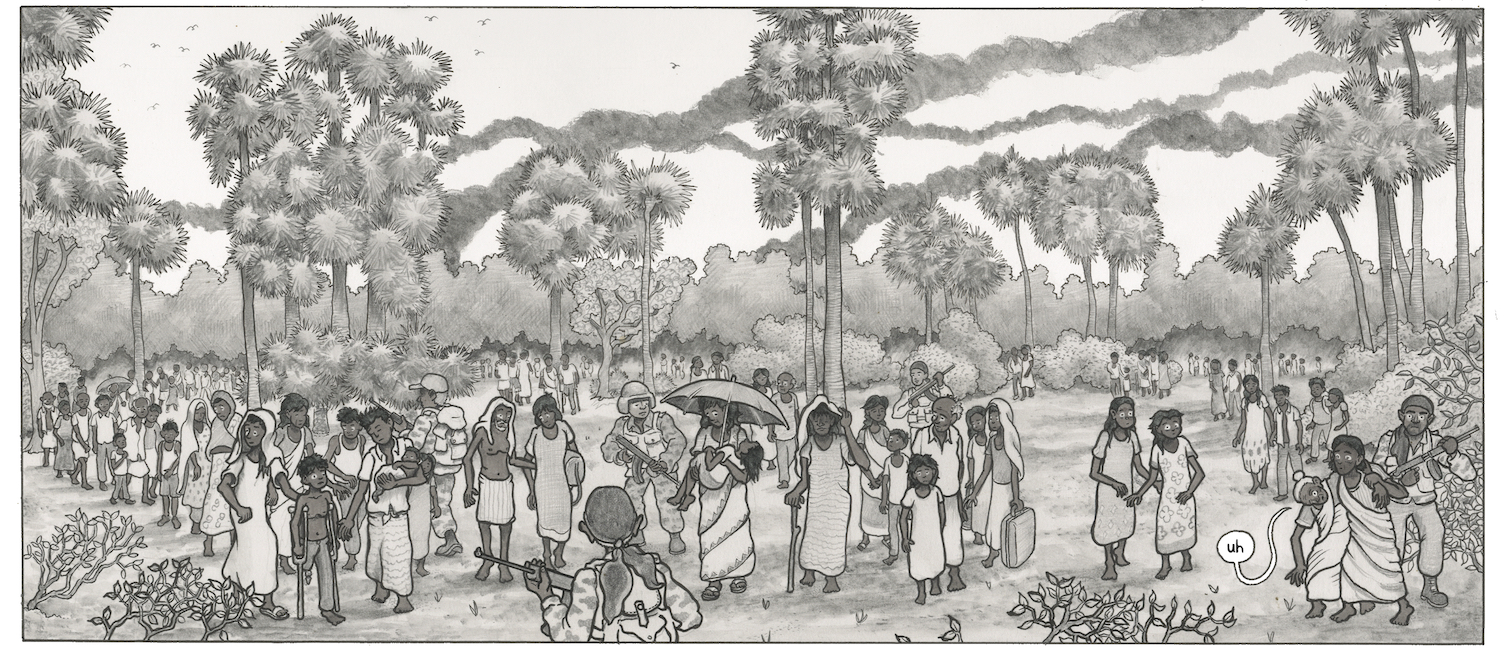

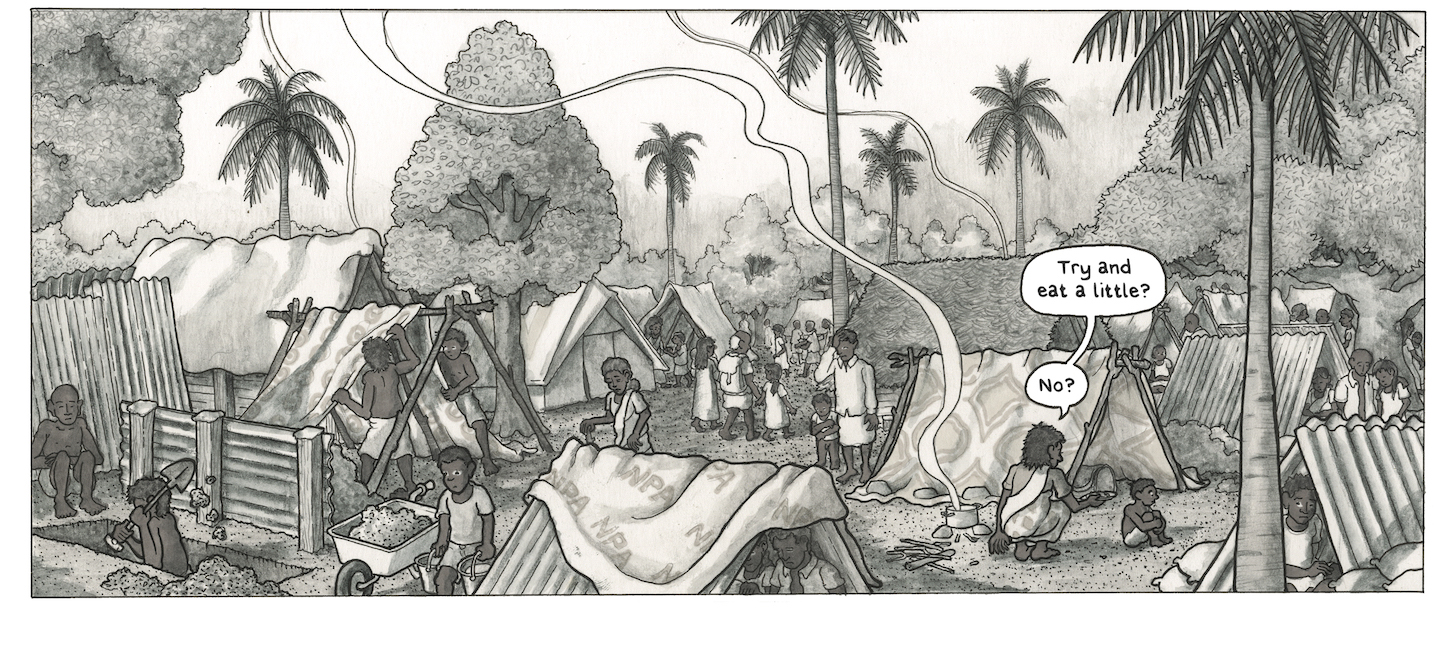

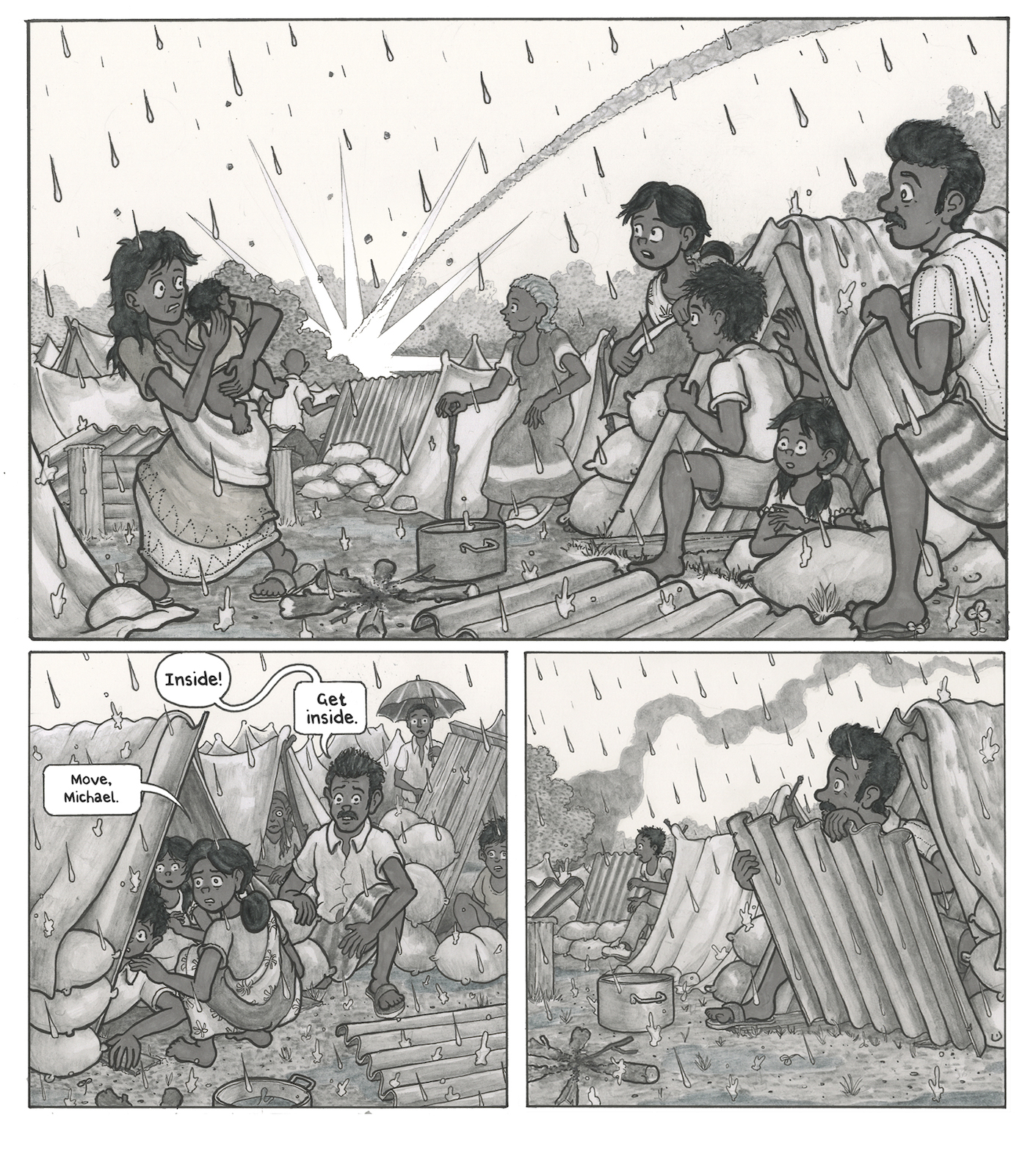

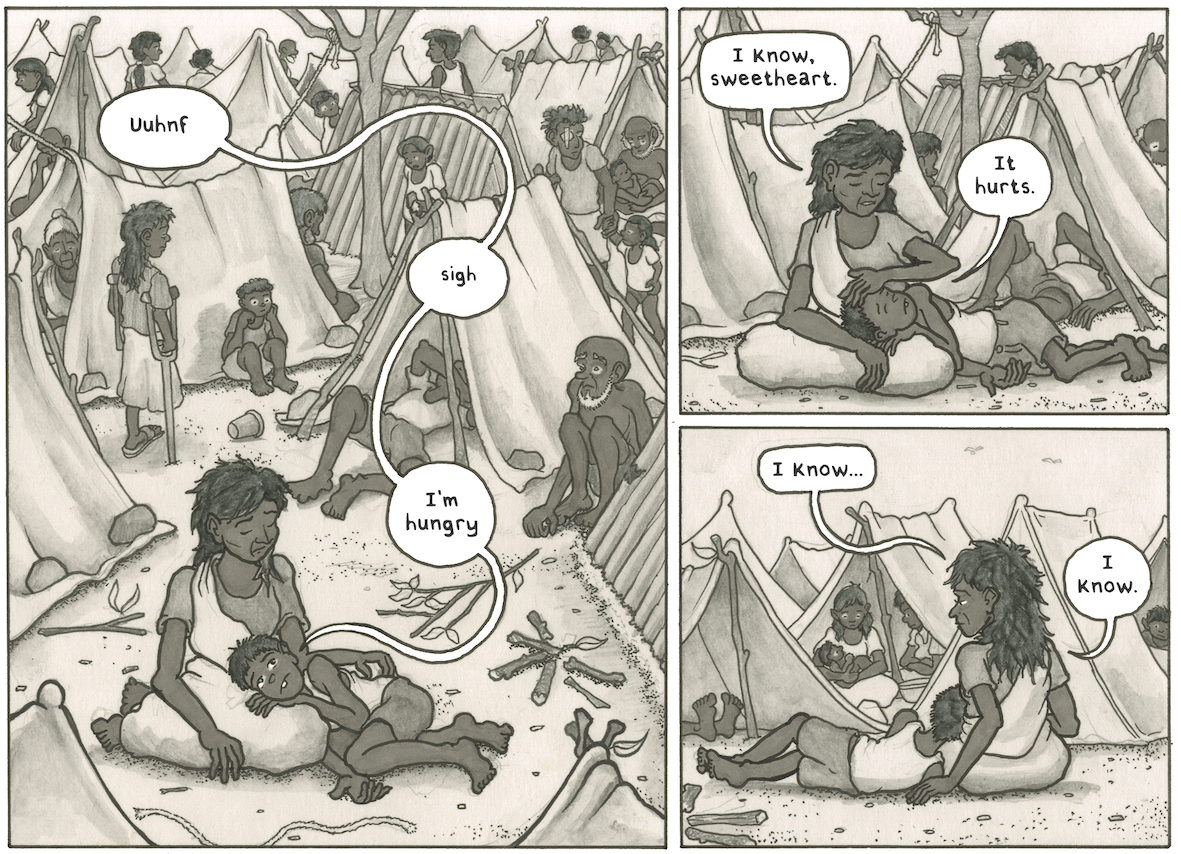

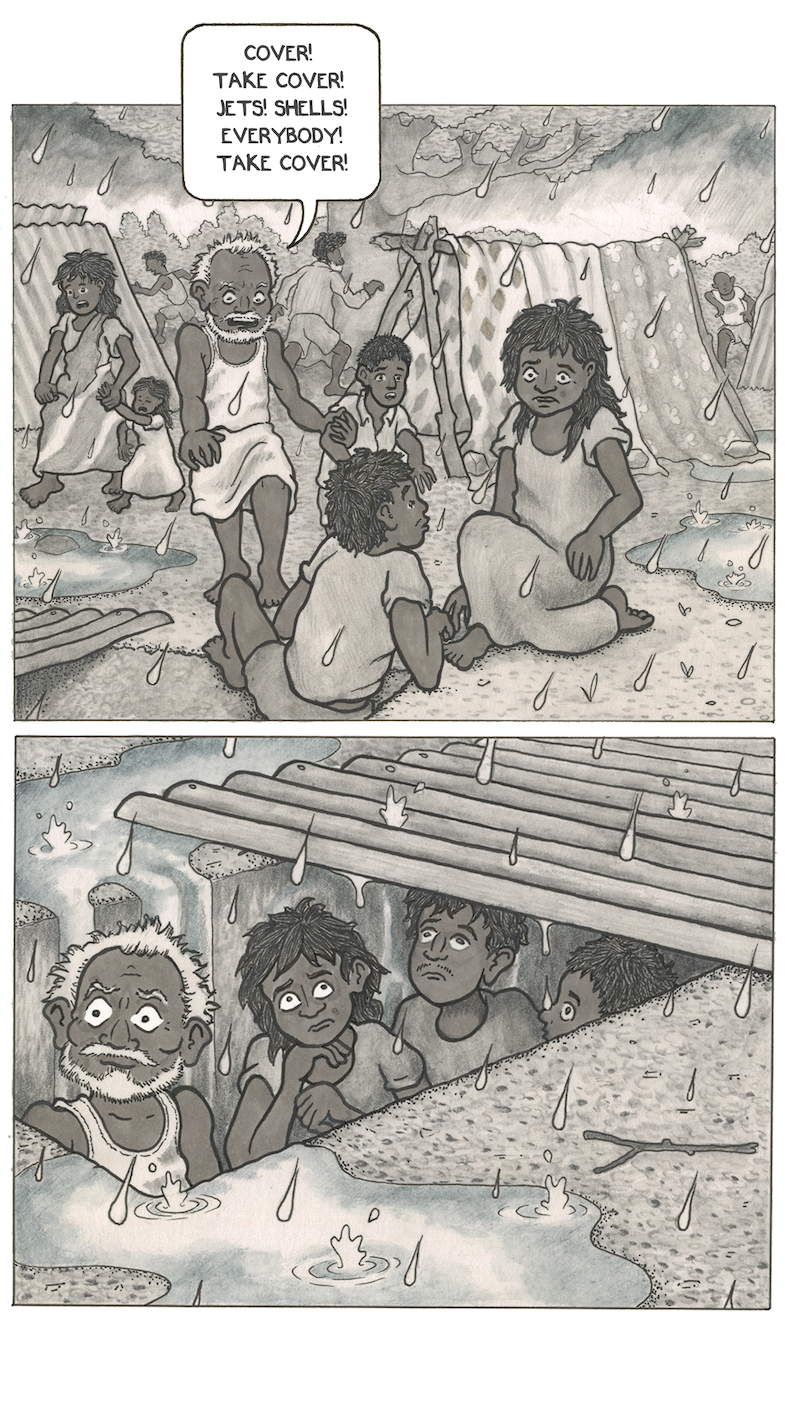

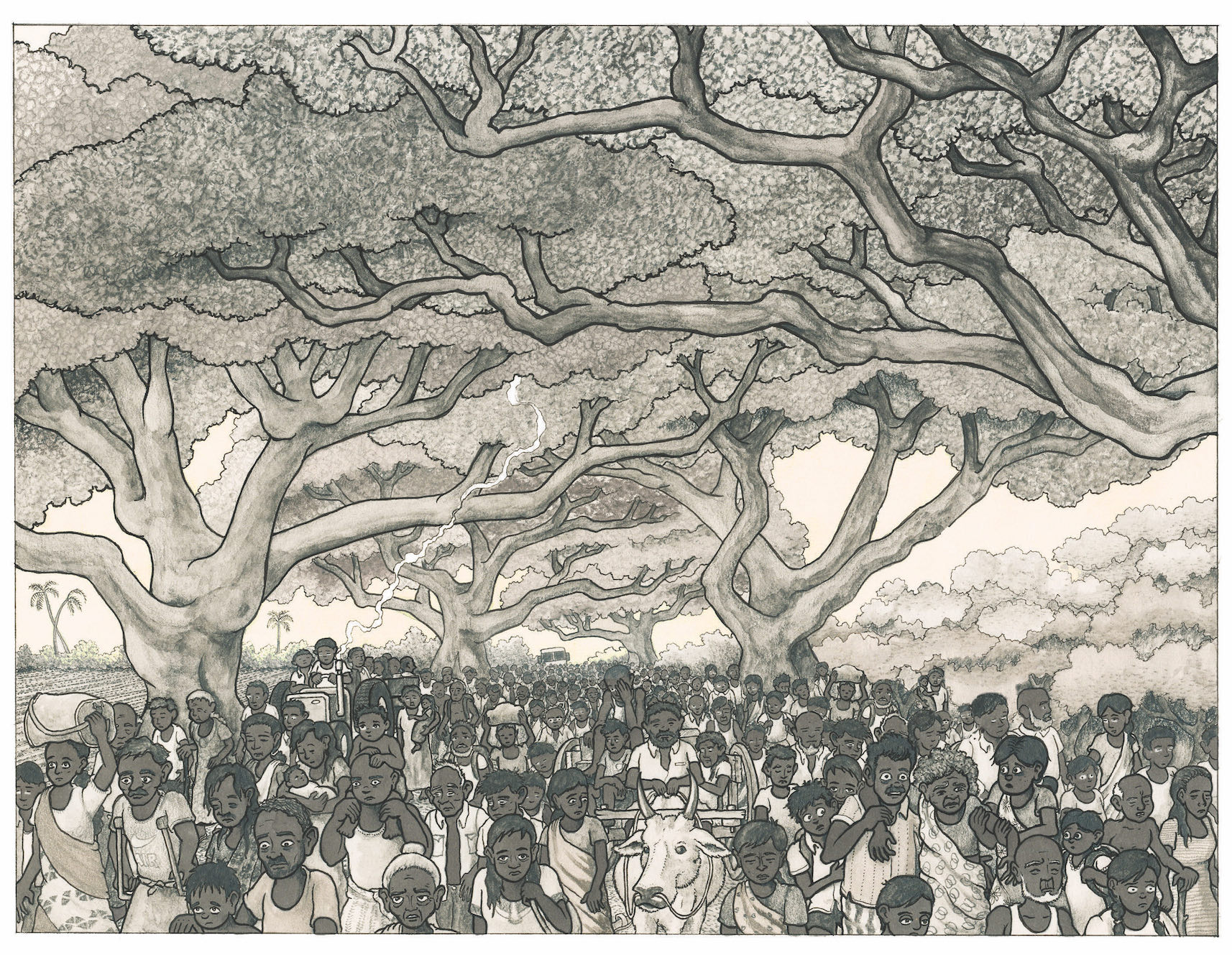

The Vanni, a graphic novel authored by Dix and illustrated by Lindsay Pollock, is a result of that heartbreak. A searing look back at the events of 2009 through the eyes of Tamil families trapped in the region, it is a powerful and moving retelling. The book is produced by Positive Negatives, an organisation Dix founded coming out of the trauma he felt.

Though stories from Tamil survivors have been retold in a range of formats Dix chose to put them in an English language comic-book style graphic novel.

"We don’t touch too much on the politics, on the global issues of the failures of Sri Lanka, either on the international community or on the Tigers or the government,” he tells us.

“It’s alluded to and mentioned throughout the book but the real focus is on the human experience of what a conflict and a migration like that experience in Sri Lanka can do to a family, can do to people’s future and how it affects generations.”

“Like with many brutal conflicts, violence rips through families and communities,” Dix writes in the afterword of the book. “Like a stone being thrown in still water, the rippling effects of war re-shape people for generations to come.”

“That’s very much how I saw Sri Lanka,” he tells us in London. "I left in 2008 and I’m still caught up in some of the ripples. And I’m an outsider to this.”

Indeed, Dix acknowledges that whilst he was in Kilinochchi at the time, he does remain very much an outsider sharing his experience of the island’s brutal ethnic conflict. “I didn’t lose family members,” he says. “I lost my temporary home of my UN home in the Vanni but it wasn’t my ancestral home.”

Indeed, Dix acknowledges that whilst he was in Kilinochchi at the time, he does remain very much an outsider sharing his experience of the island’s brutal ethnic conflict. “I didn’t lose family members,” he says. “I lost my temporary home of my UN home in the Vanni but it wasn’t my ancestral home.”

Having spent several years in the region, he did see several glimpses of life in the Vanni under the LTTE, most pointedly at the Maaveerar Naal commemorations he attended. “I went to three ‘martyrs nights’ memorials whilst I was in Kilinochchi over the course of those 4 years,” he recalls. “And you know, saw the candles and the way that they worshipped the dead… It was always a strange experience.”

Dix also tells of friends he made and lost during his time there and his emotional return to the North-East in 2017. “I met with old friends,” he says with a smile. “I had idayappam and sambal and sothi and all of that lovely stuff. We exchanged stories and cried and hugged.”

But his visit also had more poignant moments. He visited Mullivaikkal, the final strip of beach where tens of thousands of Tamil civilians were massacred by Sri Lankan artillery fire. "I felt quite ill standing there on that beach,” he says. “I don’t really have words to express that. But it was haunting, it was difficult.”

His visit to the Kanagapuram Thuyilum Ilam, the LTTE martyrs cemetery that the Sri Lankan military razed to the ground, also stands out. It was the same venue he had visited during his time in the Vanni for Maaveerar Naal commemorations. “To go back there and see just a flat field but then this pyramid of rubble and some gravestones was also incredibly haunting and difficult,” he says.

“I’m not saying the way that Sri Lanka’s government went in and razed that stuff to the ground,” he adds. “From their military cultural perspective, I can see why they would do that… But from a Tamil perspective that is so disrespectful. Not just disrespectful, that is erasing of history. For the community that’s left there, that’s just heartbreaking. Because those are the gravestones - the memories of your children and your families and your history.”

The destruction of those cemeteries is just one aspect of how the conflict continues, notes Dix. “Conflict doesn’t stop in May 2009 when the bombs stopped,” he says. “It continues to ripple for generations.”

That continuation is described in ‘The Vanni’ as Antoni struggles not only with fleeing Sri Lanka but with the asylum process in the United Kingdom, where he eventually ends up. Indeed, the asylum process in and of itself, is something that is enough for a sequel, notes Dix.

“That’s a whole other conflict story that people are traumatised about going through,” he says. And from his interviews with Tamils around the world, he notes that not all asylum applications have been successful.

“Of all the people that we interviewed, we could have gone down any single one of those endings. It could be the border police come and get you on a Friday afternoon when you get your benefits checked, send you to Gatwick to a holding facility and fly you back to Sri Lanka, into the arms of CID. And you get sent back with your asylum papers. So suddenly the Sri Lankan government know what you’ve been telling the British government about the way you’ve been treated and tortured and war crimes and human rights abuses and whatever… And also people were never seen again. They got off the plane and disappeared.”

“Another truth would be to have Antoni continuing to stay here but his wife and daughter didn’t come over and couldn’t get their visas to come over - so he’s left here alone, with the trauma and separated for years and years and years, in debt to a cousin who paid for him to come over.”

It is these true stories of loss, that meant Dix tried to ensure the narrative arc ended with a smaller victory for this character, who found refuge in London. But he knows that even in London, the trauma doesn’t end there. Dix himself has suffered with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder after leaving the Vanni.

“I struggled for three years having counselling,” he says. “I remember standing on the London Underground one evening and considering walking in front of the train. I mean I had suicidal thoughts.”

“On an emotional, personal level, the sense of abandonment, when you are caught up in those mechanisms, and you as an individual, as a 32-year-old man who has been working in Vanni, building genuine friendships, love, your staff that you manage, you are friends with these people and you are told to leave. And you drive out there. Messes you up. On quite a profound level.”

A decade on from the massacres at Mullivaikkal and with survivors still searching for accountability, we asked Dix what he would say to people like Antoni if he could speak to them now.

It is a difficult question. “Sorry,” he replies.

“I don’t know what you say to someone who has been through such a failure. Although the book isn’t political. The UN failed its mission.”

“I don’t think we were accountable for the bombs being thrown at each other and the recruitment of civilians and children, sexual violence… but we need to be accountable for holding up all of these things that we talk about, of human rights, of war crimes.”

“People knew what was going on in Sri Lanka. There was satellite imagery. They knew what was happening and they wanted this wrapped up quickly, to get rid of another terrorist organisation in the eyes of the world. But who made that terrorist organisation? These things don’t come out of nowhere.”

“For us to now sit in the 21st century and go you know ‘that’s not my problem’… well, it kind of is, you know. So step up. Step up.”

-----

The Vanni is available to buy on Amazon. See here.

See more from Positive Negatives, the company behind The Vanni, here.

We need your support

Sri Lanka is one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a journalist. Tamil journalists are particularly at threat, with at least 41 media workers known to have been killed by the Sri Lankan state or its paramilitaries during and after the armed conflict.

Despite the risks, our team on the ground remain committed to providing detailed and accurate reporting of developments in the Tamil homeland, across the island and around the world, as well as providing expert analysis and insight from the Tamil point of view

We need your support in keeping our journalism going. Support our work today.

For more ways to donate visit https://donate.tamilguardian.com.